Review: The Ordinary Spacemanby Jeff Foust

|

| Anderson writes in the book’s introduction that he wanted The Ordinary Spaceman “to be free of the mundane and politically correct.” That is certainly true. |

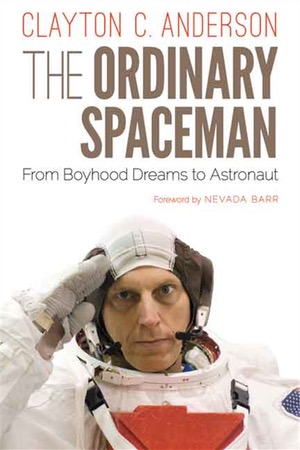

But, perhaps among that elite group, someone like Clayton Anderson was, well, ordinary. Selected in 1998, he flew on a five-month International Space Station mission in 2007 and on STS-131, one the last shuttle missions, in 2010. He had his share of firsts, like being the first native of Nebraska to fly in space, but there wasn’t that much, good or bad, that caused him to stand out among his astronaut peers. Fortunately, his memoir, The Ordinary Spaceman, is not an ordinary astronaut biography.

At first, the book does have the feel of a typical astronaut biography. Anderson recalls his childhood in Nebraska, where he says he first dreamed of becoming an astronaut watching the Apollo 8 mission as a nine-year-old (his mother, he claims, believes was interested even earlier than that.) That led to degrees in physics and aerospace engineering, then an engineering job at the Johnson Space Center, where he soon started applying for the astronaut corps. He writes that he applied fifteen times before he was finally selected in 1998. That works out to one application a year starting in the early 1980s, although NASA did not select fifteen astronaut classes during this time. He doesn’t go into detail about each attempt, but clearly he was motivated to keep trying.

The book gets more interesting, and less ordinary, when Anderson becomes an astronaut. He recounts the challenges of astronaut training, in both the US and Russia with candor. He acknowledges that, during his time on the ISS, he aggravated mission controllers: he thought he was trying to point out inefficiencies and ways things could be done better, while those on the ground couldn’t understand why he simply couldn’t follow instructions, leading to tensions. He includes in the book an assessment of his ISS mission by the Astronaut Evaluation Board: “He tended to be a bit too casual with Mission Control, and sometimes too frank, and he could have been more patient during stressful times.”

He earned back trust among NASA management to earn a second trip to space on STS-131. He nearly spoiled it, though, with an ill-advised email complaining, profanely, about the federal government’s “Fed Traveler” travel system he was struggling to use. (That might earn him folk hero status among other federal employees who have used, and complained about, that system.) He stayed on the mission and performed well, but after his flight he found his opportunities for future missions limited. “I have much better choices to fly in space than you,” he recalls the chief of the astronaut office at the time, Peggy Whitson, telling him. Anderson retired from the astronaut corps in early 2013.

| “Back inside, relaxing over sips of Russian cognac, forever obliterating the U.S. Space Program’s assertion that there is no alcohol aboard the International Space Station, we felt good.” |

Anderson writes in the book’s introduction that he wanted The Ordinary Spaceman “to be free of the mundane and politically correct.” That is certainly true. There’s a bit of a scatological flavor to portions of his book, whether it’s describing in great detail how one uses the toilet in space or the enema he received prior to a proctologic medical exam. But he also frankly portrays the physical struggles he experienced adapting to gravity after five months in space, including nausea and, yes, the need to use the toilet.

He also tweaks some of his fellow astronauts, like the ones who partied a little too hard on a visit to New Orleans during Mardi Gras, as well as the agency bureaucracy that he butted heads with. And, he dispels one long-standing claim about life on the ISS, as he describes activities with two Russian cosmonauts after a spacewalk. “Back inside, relaxing over sips of Russian cognac, forever obliterating the U.S. Space Program’s assertion that there is no alcohol aboard the International Space Station, we felt good.”

The book ends with his departure from the astronaut corps, and his uncertainty about what would come next (which, not discussed in the book, has included teaching at his grad school alma mater, Iowa State University.) Anderson, though, is grateful for the opportunity he had to be an astronaut and realize a boyhood dream. He may have been an ordinary spaceman, but The Ordinary Spaceman demonstrates he is certainly not ordinary.