Review: Leaving Orbitby Jeff Foust

|

| The book is not an insider’s account of the shuttle program’s end but rather a memoir of her own experiences witnessing those final flights. |

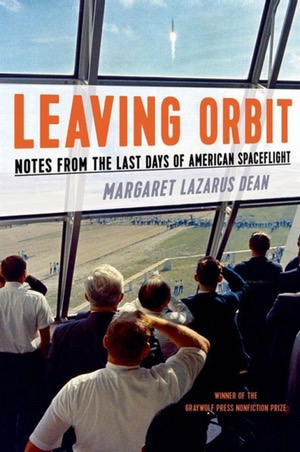

Koppel’s essay was a review of Leaving Orbit by Margaret Lazarus Dean, a novelist and professor at the University of Tennessee. The book’s subtitle, Notes from the Last Days of American Spaceflight, will set space advocates on edge like Koppel’s comments. Despite that title, the book is an enjoyable read overall about the end of the shuttle program from an outsider’s point of view, even if readers don’t share her skepticism about the future.

Dean, whose earlier novel The Times It Takes to Fall used the 80s-era shuttle program, including the Challenger accident, as a backdrop, is motivated by a behind-the-scenes visit to the Kennedy Space Center to follow the end of the shuttle program, attending the final three shuttle launches in 2011. She wants to understand why the shuttle program is ending, and what the nation is giving up by retiring the shuttle and giving up—at least temporarily—the ability to launch people into orbit.

So Dean starts a series of road trips from Tennessee to KSC, witnessing the final launches from a public viewing site outside the center, an employee viewing area at the center, and finally the KSC Press Site. She is inspired by Norman Mailer’s Of a Fire on the Moon, his account of the Apollo 11 mission, but fortunately the reader is spared Mailer’s prose and oversized ego. The book is not an insider’s account of the shuttle program’s end—her primary NASA contact was a KSC employee who emailed her after reading her earlier novel—but rather a memoir of her own experiences witnessing those final flights.

There is a palpable frustration throughout the pages of Leaving Orbit about the end of the shuttle program and, in Dean’s view, the end, perhaps, of all US human spaceflight. She’s disappointed in students in a writing class she teaches who don’t know the basics of space history, and in politicians who, she believes, don’t give NASA the support and funding it needs to do, well, something involving people in space.

If there’s a flaw in Dean’s examination of the end of the shuttle program, it’s that she places too much faith on NASA itself. The agency, she believes, could do so much more in human spaceflight if Congress would just stop meddling and increase NASA’s budget: “as a nation, we elect representatives who thwart NASA, and then we blame NASA for its lack of vision,” she writes. Later, discussing the shuttle’s inability to achieve its cost and flight rate goals, she concludes, “It’s not NASA’s fault that the projection never came true—with the generous resources of the Apollo era, they probably could have done it.”

| It’s clear she’s not a fan of commercial spaceflight: “getting to space as cheaply as possible with an emphasis on catering to paying customers only serves to rob spaceflight of the things I love most about it.” |

That seems unlikely: the shuttle stretched the limits of 1970s technology and, as remarkable a vehicle as it was, the goals set out for it were in retrospect simply not realistic, no matter how much money a generous Congress might have showered on the program. The representatives who “thwart” NASA in Congress rarely actively oppose the agency in general: they simply pay little attention to it, because it is not a priority to them or their constituents, like Dean’s students, who know little about space history. As the saying goes, we get the government—and the government-run space program—we deserve.

Her belief that the era of American human spaceflight is ending is based on her doubts that Orion and SLS will fly anytime soon, if at all, as well as general skepticism, even distaste, for commercial human spaceflight. She returns to KSC nearly a year after the last shuttle launch to see a SpaceX Falcon 9 launch (scrubbed because of an engine glitch) but it’s clear she’s not a fan: “getting to space as cheaply as possible with an emphasis on catering to paying customers only serves to rob spaceflight of the things I love most about it.”

That skepticism results in a little sloppiness: she calls that May 2012 launch “the first launch from Cape Canaveral operated by a private company,” when it was, in fact, SpaceX’s third Falcon 9 launch from there, not to mention years of commercial launches by other companies before it. She later calls a Dragon docking with the ISS in March 2013 the first such docking; that actually took place on the May 2012 mission whose initial launch attempt she saw scrubbed. However, she acknowledges she warms a bit to the company, noting she was “pleased and confused” when she watched the webcast of the second, successful launch, and calls SpaceX president Gwynne Shotwell “intense and sincere and kind of adorable.”

Dean, though, may have a point about the end of the shuttle program being an end of at least a certain type of American spaceflight: even if NASA does continue with its long-term plans leading to human missions to Mars some time in the 2030s—or later—they will be done on a different scale and frequency than the shuttle program she cherished and the Apollo program she admired. American human spaceflight may not be over, but Dean did witness, and chronicle, an era that is unlikely to be repeated.