Phase Zero and the unique parallels of space and cyberby Jamie J. Johnson

|

| If we can form a treaty with Russia at the height of the Cold War, why not a new space treaty today? And if we truly cannot at this time, are we already in a Cold War of another kind? |

China is currently ramping up capabilities to monitor satellites and debris in orbit, which may be a precursor for more capability in the future.5 An increase in focus for US Strategic Command has been toward space situational awareness (SSA), and not just being “FAA in space.”6 Watching debris in orbit and decreasing the probability of collisions is important, but SSA today means much more. SSA is knowing the health and operational availability of all space assets; knowing what assets in space and on the ground are held at risk by potential threats and by whom; where our friends, adversaries, and ambiguous assets are in orbit; and knowing what can be done immediately after determining a threat is present. To make matters worse, all of the answers to these questions change rapidly with time. Ground systems are vulnerable too, which makes efforts like Operation Silent Sentry that detect, characterize, and locate sources of interference very critical.7

Training and utilization of military roles also requires attention. Our leaders have already questioned whether we need the military to be the “FAA in space,” or if civilians or contractors can best do that job.8 This generates questions. Is US military manpower best utilized watching things go around in orbit, or are they best expertly managing all the questions and answers that SSA generates as mentioned above? Is the military today being trained with the right mindset and tools to make the right decisions in quick-turn observe-orient-decide-act (OODA) loop environments, in which the smallest movements could have largely strategic long-term effects?

We have career specialty codes for Air Battle Managers, but we do not have a specialty for Space Battle Managers. We have Airborne Early Warning and Control (AWACS), but we do not have personnel executing congruent objectives for the Joint Space Operations Center. Battle managers could deploy with their units to execute tactics, techniques and procedures in theater on developing prototypes as technology quickly evolves, as it has shown to be fruitful in recent past.9

The final factor with extra focus is international policy. New dynamic, non-kinetic, and hard-to-attribute threats that have been developed for use in space have outpaced and outdated current doctrine, inspiring a much needed cultural change for space warriors. Critics say that while we need to defend our assets and lead the way in technology, the US could also lead the way in new space arms control policy to provide an update to the 1967 UN Outer Space Treaty.10 The 2015 National Security Strategy (NSS) suggests enforcement of an International Code of Conduct on Outer Space Activities, which could increase openness and hold nations accountable for actions not in line with “peaceful purposes.”11

We are undoubtedly in a key position and time to drive toward diplomacy and cooperation with China and Russia. China’s ambiguous testing of missiles and our distrust of Russia’s propulsion technologies have recently created rifts, but open discussions among all parties regarding the future of space could be the most responsible avenue to take. While still partnering with commercial firms to lead the way in technology and disaggregation, the US can still uphold new agreements and set the gold standard for awareness and attribution in space. If we can form a treaty with Russia at the height of the Cold War, why not a new space treaty today? And if we truly cannot at this time, are we already in a Cold War of another kind?

Cyber. There was a time when cyber was simply about making sure we protect our information and our networks: ensuring firewalls protect us from viruses, using encrypted methods of communications, and strengthening our passwords. With over seven million networked DoD devices to protect, those objectives are still important, but they are far from everything that cyber entails. Much like for space, awareness is key. We must know in real time what is threatened, by what, and what can be done about it. Cyber situational awareness (CSA) is not a common term for cyber, but perhaps should be since space and cyber are so closely related. All of the awareness questions posed above for space can be posed for cyber. Cyber is unique because it generates questions about the best course of action to react to attacks, what constitutes “use of force”, and how diplomacy can prevent future conflicts involving the cyber domain.

| We have been warned of a possible “space Pearl Harbor,” but it is hard to argue how the OPM breach could not have been a Pearl Harbor of the cyber variety. |

Our current level of awareness has not saved us from events like the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) breach, which potentially identified almost everybody in the United States with a security clearance and exposed the information of up to 14 million current and former civilian US government employees.12 For perspective, the OPM attack of 2015 far surpasses the amount of data involved in, and potential lasting damage of, the attack on Sony Pictures Entertainment in 2014. To not think of the latest attack as having lasting strategic effects would be quite ignorant.13 To have such cyber security wakeup calls for decades, and yet continue to hit the snooze button, shows a clear misunderstanding of what we should all know to be true: for cyber, we may already be at war.

Our cyber defenses have been criticized as imperfect, quickly outdated, and expensive to keep up.14 Not only are a lot of people vulnerable to identity theft, this kind of breach severely inhibits the way we operate as a military, especially members of the intelligence community. We have been warned of a possible “space Pearl Harbor,” but it is hard to argue how the OPM breach could not have been a Pearl Harbor of the cyber variety. When adversaries do not know what response to expect—or expect no response at all—and attribution difficulties remain, knowing how to react becomes nebulous.

It has been said that cyber activities that “result in death, injury, or significant destruction” would likely be viewed as a use of force.15 The 2015 DoD cyber strategy points to “lives lost, property destroyed, policy objectives harmed, or economic interests affected” as defining a destructive attack. It also claims that the US will respond to a cyber attack on US interests through defense capabilities, especially since the Director of National Intelligence placed the cyber threat ahead of terrorism for the first time since September 11, 2001.16 While there may be ways to cause physical harm through the use of cyber, we do not consider non-physical uses of force because they are too new. Within this non-physical domain, how is the massive theft of OPM data not seen as a major attack? How is someone stealing millions of individuals’ private data not seen as a use of force? Historically, the US has used massive amounts of deadly force and lost scores of our own men and women to protect vital national interests in the Middle East. Is the data of every government employee and military member to include clearances, addresses, health records, and identities not seen as a vital national interest or a major security risk? Scholars have addressed the fact that we tend to focus on hard effects of cyber attacks rather than intent.17 Hostile intentions are enough to put someone in jail and cause more severe punishment, as in a public trial, but are overlooked with cyber threats. With improved attribution, hostile intent, rather than effects alone, can be used to determine if use of force in response is justified.

Concerning cyber policy, the US could benefit from diplomatic partnerships that achieve goals toward implementation of an international “Cyber Treaty.” As the 2015 NSS suggests, collectively with partner nations, we can develop new laws and enforce long-standing norms including protection of intellectual property, online freedom and respect for civilian infrastructure.18 With allied nations, the US could form technological tools and intelligence-gathering measures to reduce the risk of cyber threats.19 The new Department of Defense Cyber Strategy emphasizes building alliances, coalitions, and partnerships abroad. Working together and force multiplying with our allies may be the best way to maintain CSA worldwide.20 Lastly, Joint Publication 5-0 (JP 5-0), begins describing notional operation plan phases with emphasis on multinational operations and cooperation in support of strategic objectives.21

| Space and cyber are different domains, but they deal with much of the same technology and defense systems. |

Space and cyber are intertwined. US Strategic Command is plainly aware that space and cyber are tightly intertwined.22 Space has become more congested and contested, while cyber has become more active and accessible. Space has systems now being deployed that were designed in the 1980s and ’90s, due to the “tyranny of the Program of Record.”23 This will become more of a problem as technology time cycles continue to outpace acquisition time cycles. Cyber has systems and software tools that are designed, developed, tested, and sustained all with real-time strokes on a keyboard. While some US space systems have unmatched capabilities requiring long acquisition times, space could learn from cyber in the way it develops new systems to ensure the latest and greatest technologies are fielded to address the most pertinent problems. Cyber has problems of its own, as most systems and measures are purely reactionary and in many cases too late to the game. Cyber could learn from space by enforcing more and more presence and persistence to diminish the probability and damage of attacks.

Space and cyber are different domains, but they deal with much of the same technology and defense systems. Everything currently in space depends on or uses software and data from existing wireless network architectures. Everything in cyber uses computing technology that can be designed for use in space. Space assets face cybersecurity threats. Threats in the cyber domain may involve space assets. Current problems in both domains can be summed up in three terms: awareness, assessment, and attribution. Awareness answers the initial questions: “what, where and when?” Assessment, as in assessment of adversary attacks, answers the questions, “are we vulnerable, were we attacked, and what do we know?” Attribution answers the question, “how did it happen and who did it?” As attacks in space and cyber become more commonplace, advanced, subtle, non-kinetic, overt, and insidious, the answers to these questions become both more challenging and important for our national security. Perfecting the quest for these answers can all be accomplished in Phase Zero.

Revisiting Phase Zero

Robert Work has stated that space defense hinges on us being in an unlikely “shooting war” with Russia or China, or both.24 He is correct in that it is unlikely that we would have such diplomatic failure that we would get into a traditional war or armed conflict with a power like China or Russia. Will we ever be in a shooting war prior to “conflicts that extend into space?” What would likely occur first? Would what we are engaged in look anything like war at all? These questions spur further discussion about Phase Zero.

While the concept of Phase Zero is relatively new, current doctrine does not clearly relate to the current state of affairs for space and cyber. Critics point to the fact that the definition in Joint Publication (JP) 5-0 draws an artificial line between pre-conflict and conflict scenarios and fails to mention any sense of acting in order to change the adversary’s will.25 JP 5-0 only mentions shaping perceptions, influencing behavior, and improving information exchange.26

| While some US space systems have unmatched capabilities requiring long acquisition times, space could learn from cyber in the way it develops new systems to ensure the latest and greatest technologies are fielded to address the most pertinent problems. |

The use of the term “active defense” by the Chinese also spurs some insights. How active can one’s defense be before it becomes offense? How much can be achieved while still being considered defense? How effective is an active defense in ensuring we do not need to use major combat operations? Ultimately, the question becomes, to what extent can Phase Zero be used to prevent war rather than just to shape it? In other words, due to the uniqueness of space and cyber, the more time and effort we spend in Phase Zero, perhaps the less time we have to spend outside of it.27

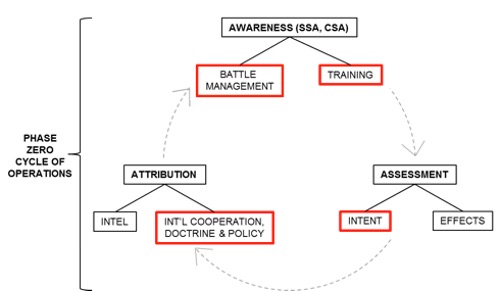

The space and cyber domains are equally conditioned to enhance awareness, assessment, and attribution capabilities while maintaining a Phase Zero presence with current threats presented by countries like China and Russia. The figure below is a proposed model summarizing the actions that can be taken within Phase Zero for both space and cyber as well as areas that require continued attention as described above.

Proposed Phase Zero Model for Space and Cyber. Areas in red require attention as the US improves its awareness, assessment, and attribution. |

Summary

We must not think of space and cyberspace as totally separate domains. As technology time cycles decrease and new hardware and software becomes more complex, more systems will blur the boundaries between domains, becoming more reliant on real time intelligence to ensure effective operations to defend our national interests. Phase Zero should not just be thought of as a way to shape major combat operations in the future, but be used to the maximum extent possible to advance the areas of awareness, assessment, and attribution in both domains. Additionally, as attacks on the US in the space and cyber domains become more insidious, Phase Zero can be used to prevent conflict and perfect our ability to actively defend national interests. As China moves toward expediting the development of a cyber force, continues to execute more provocative tests in space, and partners with Russia, the US has the opportunity to update international policy and collectively attribute nations who are assessed to have damaging intent, even if effects are not severe. As nations are positively attributed, peace can be kept through the use of various instruments of power. To intervene as little as possible in the future, we must intervene as early as possible.28 This should be executed by all means necessary afforded by the uniqueness of space and cyber.

Endnotes

- Elsa Kania, “China’s Military Strategy: A Cyber Perspective,” 3 June 2015.

- Scott D. McDonald, Brock Jones, and Jason M. Frazee, “Phase Zero: How China Exploits It, Why the United States Does Not, Naval War College Review, Summer 2012, Vol. 65, No. 3, 123.

- Cory Bennett, “Chinese military to put new focus on cyber,” 27 May 2015.

- Stew Magnuson, “Work: U.S. Must Demonstrate Ability to Fight in Space,” 23 June 2015.

- “China launches space junk monitoring center,” 10 June 2015.

- Sydney J. Freedberg, “STRATCOM Must Be Warfighters, Not FAA in Space,” 16 June 2015.

- Alexandre Montes, “Silent Sentry meets a decade of interstellar combat support,” 17 June 2015.

- STRATCOM Must Be Warfighters.

- Silent Sentry.

- Caleb Pomeroy, “Op-ed: Why the U.S. Should Be a Leader in Space Arms Control,” 1 June 2015.

- “National Security Strategy”, February 2015, 13.

- “Officials: Second hack exposed military and intel data,” 12 June 2015.

- Second hack.

- Andrew Beatty, “Obama struggles for deterrence amid wave of cyberattacks,” 6 June 2015.

- Ibid.

- Ashton B. Carter, “The DoD Cyber Strategy,” The Department of Defense, 17 Apr 2015, 9.

- Herbert S. Lin, “Offensive Cyber Operations and the Use of Force,” Journal of National Security Law & Policy, Vol 4, No. 63, 2010, 76.

- NSS, 13.

- Gabi Siboni, “A good defense requires a good offense, even in cyberspace,” 27 May 2015.

- Cyber Strategy, 4.

- Joint Publication 5-0, Joint Operations Planning, 11 August 2011, III-42.

- STRATCOM Must Be Warfighters.

- Tom Taverney, “How military space systems need to deal with change,” 8 June 2015.

- U.S. Must Demonstrate.

- Phase Zero: How China Exploits It, 132.

- JP 5-0, III-42.

- Tyrone L. Groh and Richard J. Bailey, Jr., “JFQ 77 – Fighting More Fires with Less Water: Phase Zero and Modified Operational Design,” National Defense University Press.

- Phase Zero: How China Exploits It, 125.