The helium-3 incantationby Dwayne Day

|

| But even years later helium-3 still pollutes the environment of discussions about human spaceflight, despite its very nebulous assumptions. |

Schmitt is probably the smartest astronaut who walked on the Moon, and certainly the most educated. He is a Harvard-trained geologist who NASA admitted to the Apollo program under pressure from Congress, and his presence undoubtedly increased the scientific return of his Apollo 17 mission as well as the entire program considering his role in training astronauts on earlier missions. Schmitt can still deliver graduate-level geology lectures if given the opportunity. But he also embraces the dubious scientific and engineering idea of mining helium-3 on the Moon for use in fusion reactors.

The last big flurry of articles and publications, and even a congressional hearing, about helium-3 fusion occurred in 2007, when NASA was still planning to send humans to the Moon. NASA did not drive that discussion then, but rather Schmitt and a few others. But even eight years later helium-3 still pollutes the environment of discussions about human spaceflight, despite its very nebulous assumptions.

Harrison Schmitt discussed helium-3 mining on the Moon during a talk at last month’s Mars Society conference in Washington. (credit: D. Day) |

Helium that wants to party

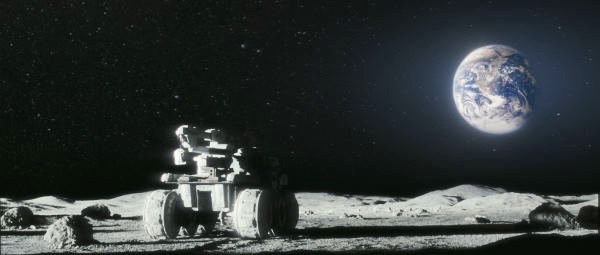

Helium-3 is an isotope of helium, which means that instead of having two protons and two neutrons, like plain old boring helium, helium-3 lives on the wild side and has a single neutron and two protons. And unless you’re new to the topic of human spaceflight, you know that helium-3 is often invoked as a reason why we need to send humans to the Moon, where helium-3 is believed by some (still not proven) to exist in relatively large quantities. Novels, television shows, and movies such as the excellent 2009 film Moon used lunar helium-3 as a plot point. In fact, whenever helium-3 on the Moon is mentioned either in news articles or fiction it is always linked to fusion power. And that creates the first problem:

There are no fusion reactors

Most people who use electricity put very little thought into how it is generated and don’t know or care if it comes from a coal-fired power plant, a windmill, or a nuclear fission reactor. But somebody who is a little more well read may be aware that electricity-generating fusion reactors do not exist. Despite decades of funding, commercial fusion power is still considered by scientists and engineers to be decades away at best. The big first step, getting the same amount of energy out of the reaction that gets put into it to make it occur, has been promised for decades and even today is apparently a decade or two away.

The long history of fusion research is somewhat reminiscent of a quote attributed to Richard Feynman: “Physics is like sex: sure it may give some practical results, but that’s not why we do it.” A lot of fusion research has been more of a physics experiment than an applied development project—maybe not exactly screwing around, but certainly not driving towards a clearly identified goal of generating commercial electricity. Even if there had been a distinct objective, it is doubtful we would have fusion power today because it is a very difficult physics problem.

| Simply put, fusion reactors using helium-3 are a development that may be decades, even centuries, away, with no clear roadmap to development or extensive funding stream to make it happen. |

But none of this is ever mentioned whenever the Moon and helium-3 comes up. And rather startlingly, many of the people who advocate sending humans to the Moon for helium-3 seem to be unaware of the current state of fusion research, or when—or if—it is likely to become commercially viable. Closely related to this is another thorny problem:

Helium-3 fusion is even more difficult than regular fusion

If researchers are able to achieve “break-even” fusion, and are then able to turn this engineering accomplishment into a commercially viable enterprise, that would involve a different approach than is required for helium-3 fusion. Controlled fusion using helium-3 requires engineering significantly more challenging than even the basic fusion that nobody has been able to accomplish despite half a century of effort. Because of the impracticality of the conventional approach, Gerald Kulcinski at the University of Wisconsin-Madison has proposed an alternative method for helium-3 fusion and has achieved some limited success, although the amount of energy that goes into this fusion reaction dwarfs the amount that comes out of it, and that has not changed significantly in the last decade or so.

Simply put, fusion reactors using helium-3 are a development that may be decades, even centuries, away, with no clear roadmap to development or extensive funding stream to make it happen. Furthermore, in the fusion research world, and in the helium-3 research field, nobody is realistically talking about the requirement to go mine the Moon for this scarce isotope. Even if they did, they would confront a third problem:

Helium-3 may be very difficult to locate and mine on the Moon

There are very few people who have addressed the subject of how much helium-3 is on the Moon and how it might be contained in lunar regolith. Their estimates are that far more helium-3 exists on the Moon than can be accessed at Earth, but that’s sort of like saying that California doesn’t really have a drought problem because the Great Lakes contain plenty of water. The problem is that helium-3 is probably spread very thinly over millions of square kilometers of lunar regolith. Collecting it would require a vast strip-mining effort with lots of machinery, not to mention equipment for locating the material in the first place. Nobody has even begun to look at the engineering and scientific developments necessary to achieve this.

There are very few US government reports that address helium-3. In 2010, the Congressional Research Service (CRS) produced a report on helium-3. CRS is a research office that works for Congress and its reports are usually narrowly focused, and consequently rather dry. But they often address topics that nobody else is writing about, and do so with objectivity and a certain amount of authority.

The 2010 CRS report discussed the potential uses for helium-3, including national security, medicine, and scientific research. The report also stated that there is currently a helium-3 shortage and that if we had more of it, we would be able to use it more widely and certainly find new uses. But notably, the report did not discuss the Moon as a viable source of helium-3, nor did it refer to fusion power. In this respect it was much like the way that the solar energy industry holds large conferences and never discusses space solar power. It should be a warning when the experts on a subject ignore an application that is enthusiastically embraced by space enthusiasts.

Wishful/magical thinking

Mining helium-3 on the Moon appears regularly as a throwaway line in lots of articles about sending humans to the Moon. Reporters merely assume it is true without questioning it or understanding the issues behind it. In fact, many popular media articles that discuss sending humans to the Moon—possibly even a majority of them—mention helium-3 and fusion. In January 2015 a slew of stories brought it up again. Stories with titles like “China is going to mine the Moon for helium-3 fusion fuel,” and “Could mining helium-3 from the Moon solve Earth’s energy problems?”

| One common attribute of many religions is their ability to incorporate superstitions or iconography or traditions. Space activism does this as well. The belief in helium-3 mining is a great example of a myth that has been incorporated into the larger enthusiasm for human spaceflight, a magical incantation that is murmured, but rarely actually discussed. |

Surprisingly, this is not merely an American habit: helium-3 mining has even been parroted by Russian, Indian, and Chinese space officials as justification for why they need to go to the Moon. The latest manifestation of this myth in the Western press is to claim that China is obsessed with, or planning to mine helium-3, as if it is vital to send Americans back to the Moon to avoid a helium-3 gap. But this is an example of a global echo chamber at work: Chinese space officials refer to helium-3 largely because they have seen it in the Western press, and then the Western press hypes it as some kind of threat posed by the Chinese lunar program.

Over the decades, many people—most notably Carl Sagan—have noted that space enthusiasm shares many characteristics with religion. People have a set of beliefs that seem perfectly logical and reasonable to them, but which they have great difficulty explaining convincingly to those who do not share the beliefs, or have an alternative set of beliefs. They also tend to not recognize the logical fallacies in their belief systems.

Of course, it’s possible to take this analogy too far. But it also has a great deal of explanatory value. One common attribute of many religions is their ability to incorporate superstitions or iconography or traditions. Space activism does this as well. There are fetishes—imbuing certain technologies with virtually supernatural abilities—and also what might be best called incantations, or things that people say almost out of unconscious habit. The belief in helium-3 mining is a great example of a myth that has been incorporated into the larger enthusiasm for human spaceflight, a magical incantation that is murmured, but rarely actually discussed.

Fortunately, NASA as an institution has been immune from the helium-3 incantation, even when human missions to the Moon were actual policy. This is probably because the agency has its own antibodies that have effectively fought it. At the very least, if a NASA official sought to invoke helium-3 for fusion reactors in a major speech or policy document it would have to be vetted with other government agencies like the Department of Energy, and would quickly be quashed. NASA’s scientists and engineers know that helium-3 is not a justification for a human lunar program, and the continued mention of helium-3 in popular articles about the Moon—or by non-American space officials—is not going to influence whether the United States sends people there or not. But you can guarantee that talk of helium-3 will flare up again whenever the discussion turns to returning humans to the Moon, but never producing much in the way of heat or light.