The Moon in the crosshairs (part 2)CIA monitoring of the Soviet manned lunar program, intelligence analysis, second phase, 1965–1968by Dwayne Day

|

| According to CIA space analyst Sayre Stevens in a 2003 interview, the CIA was really perplexed by the Soviet construction at the new launch complex—it was proceeding at too slow a pace to be competitive with Apollo. |

In October 1964, the CIA’s Office of Scientific Intelligence produced a report on new space facilities at the Baikonur Cosmodrome, which the intelligence community referred to as Tyura-Tam. The report concluded that it was still too early to declare the big Complex J construction area to be an actual launch site because no evidence of launch pad construction had yet been seen. The Soviet manned space program was also showing no progress after a flurry of launches in 1961–1962. “Within the capability of their SS-6 booster they have apparently been marking time in manned flight program for almost two years,” the report stated. But given the space program’s propaganda value, “the manned program is expected to enter a new phase, possibly by the latter half of 1964,” the authors concluded.

In January 1965, the US intelligence community produced a new National Intelligence Estimate on the Soviet Space Program. The report stated, “We estimate that the Soviets also have under development a very large booster with a thrust on the order of five million pounds. We believe it unlikely that this vehicle will be flight-tested before 1967, but it is possible that such a test could occur in the latter half of 1966.” The report suggested that such a booster may have been intended to orbit a large space station. But it noted: “Considering the variety of techniques open to the Soviets for conducting a manned lunar landing, such a new booster also could be used for this mission.”

Lacking the clear evidence of a Soviet lunar program, the NIE continued its informed speculation: “It seems certain that the Soviets intend to land a man on the Moon sometime in the future, but there are at present no specific indications of any such project aimed at 1968-1969, i.e. intended to be competitive with the U.S. Apollo project.”

One paragraph later the NIE stated:

“If the earth-orbit rendezvous technique were used, some one to three rendezvous probably would be required, depending on the actual thrust of the booster and Soviet success in reducing the weights of structures and components below present levels. Thus a Soviet attempt at a manned lunar landing in a period competitive with the present U.S. Apollo schedule cannot be ruled out.

To compete in this fashion, however, the Soviets would have had to make an initial decision to this effect several years ago and to have sustained a high priority for the project in the ensuing period… The appearance and non-appearance of various technical developments, economic considerations, leadership statements, and continued commitments to other major space missions all lead us to the conclusion that a manned lunar landing ahead of the present Apollo schedule probably is not a Soviet objective.”

According to CIA space analyst Sayre Stevens in a 2003 interview, the CIA was really perplexed by the Soviet construction at the new launch complex—it was proceeding at too slow a pace to be competitive with Apollo. The Apollo program was still tentatively on schedule for manned launches as early as late 1966, with a lunar landing attempt possibly in early to mid 1968. Many NASA officials believed that this schedule would slip, but the Soviets had to assume that it would not and would have to plan to beat the Americans. However, Soviet construction moved too slow to meet that schedule, and in fact was slower than construction at other Soviet missile facilities. It was hard to determine why the Soviets would engage in a lunar program unless their goal was to beat the United States—there was little value in finishing second. Had they worked harder, American intelligence analysts might have considered this a better indication that they were racing Apollo to the Moon, rather than pursuing other goals, like a space station.

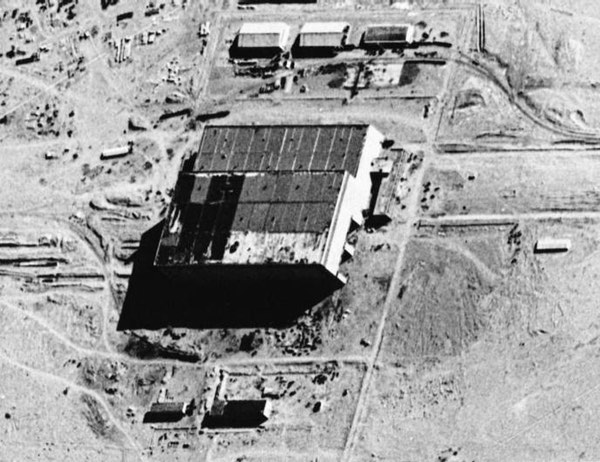

In 1964 American satellites had detected the start of launch pad construction at the new facility. All through 1965 CORONA and GAMBIT satellites flew over Tyura-Tam, taking their pictures of the large construction effort underway there. Soon they detected massive excavation of another launch pad to the northwest of the first one. They designated the first pad “J1” and the new pad they designated “J2.”

In late October 1965, the CIA’s Office of Research and Reports of the Directorate of Intelligence produced a detailed study of the construction of Complex J. Despite its sponsor, this was still primarily an imagery report, for it mentioned nothing of signals intelligence or Soviet statements about its space programs. The report’s authors concluded that Complex J would be ready for initial operations toward the end of the third quarter of 1966, with the second launch pad becoming available in mid-1967.

Complex J was clearly a large facility intended to support rockets in the Saturn V class and the analysts determined, “Manned lunar landing and a large space station are definite possibilities.” As if to emphasize this point, they noted the immense cost of the facility and stated “The program for which Complex J is being built cannot be identified specifically, but the scale of construction and size of capital investment at Complex J suggest a program comparable in size to the U.S. Apollo program.”

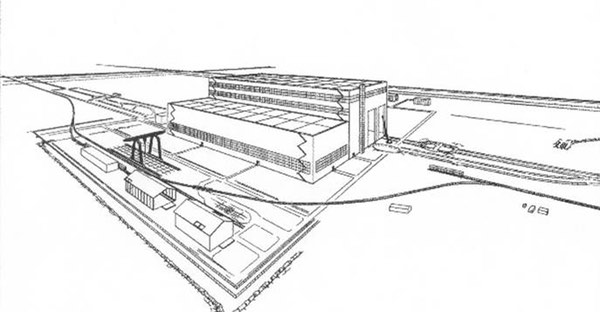

Complex J essentially had four main components: the construction support area, which included housing for the construction workers; the apartment and technical support area for housing the people who would actually work on the rocket and spacecraft to be launched from the facility; the assembly and checkout area; and the launch pads.

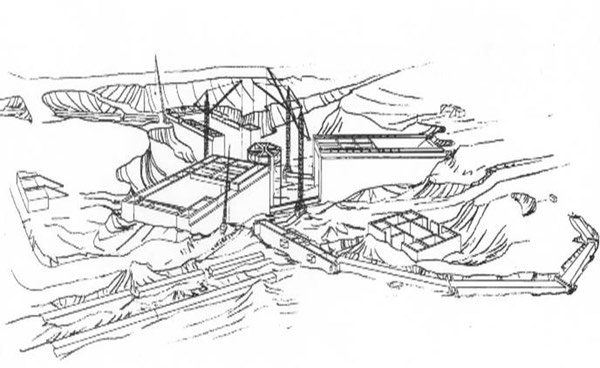

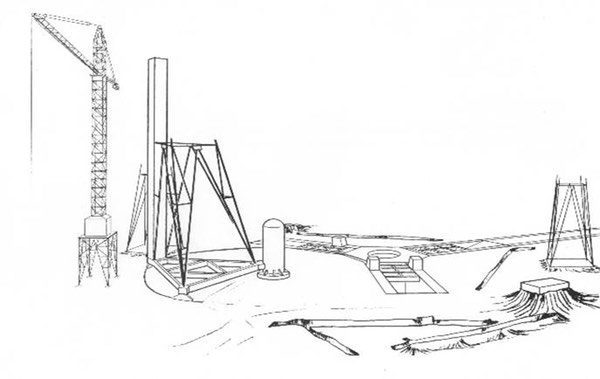

In a March 1965 report, the CIA’s Photographic Interpretation Division, or PID, produced an initial assessment of the launch pads at Complex J. The first pad had a large pear-shaped excavation about 215 meters (700 feet) long, 150 meters (500 feet) wide, and 37 to 42 meters (120 to 140 feet) deep. Large square concrete legs were being built from the floor of the excavation and a rectangular sump for water recovery was being constructed in the bottom of the pit. “The latest photography indicates that Pad J1 will be a massive concrete launch stand with a water-cooled flame deflector and water recovery system,” the report concluded.

| According to CIA space analyst Sayre Stevens in a 2003 interview, the CIA was really perplexed by the Soviet construction at the new launch complex—it was proceeding at too slow a pace to be competitive with Apollo. |

In addition to the unknowns, the analysts also drew some mistaken conclusions from the available data. For example, satellite photography had revealed the start of excavation of parallel trenches about 10 feet wide and 60 feet apart leading from the large missile assembly building toward the launch area. The analysts concluded that they were the foundations for heavy gantry rails and accurately concluded that this indicated the probable intention to fully assemble the vehicle and the payload in or near the missile assembly building. But they also inaccurately concluded that the gentle curve leading toward the launch area indicated that a very tall, heavy gantry would use the track and roll the vehicle to the pad while vertical, rather than horizontally like all other Soviet missiles and rockets.

The Soviet Union was probably spending between $10 and $18 billion on their new space program, clearly a large amount of money. |

The report even included a hypothetical illustration of what the final launch pad configuration might look like. It looked remarkably similar to the famed Complex A Sputnik pad at Tyura-Tam, which had a large pear-shaped flame trench carved into the ground. The intelligence analysts based this assumption on the fact that so far all they had seen at the pads were giant excavations, with roads for the dump trucks to remove the dirt. They did not yet know if the Soviet workers would fill in those excavations. (By late 1965 it became apparent from satellite photos that the Soviets were constructing a concrete structure inside the excavation and filling part of it in, not simply building a platform atop massive legs.)

The report’s authors used a 1959 Soviet document on the construction costs of buildings and structures to determine how much the Soviet Union was spending on Complex J. They then used an August 1964 CIA report on ruble-dollar conversions to calculate the costs in dollars. They determined that Complex J cost from $300–360 million, or about 70–85 percent the cost of NASA’s Launch Complex 39 for launching the Saturn V.

The analysts noted that in the United States, the capital investment in Launch Complex 39 amounted to slightly more than two percent of the $20 billion cost of the Apollo Program. They assumed a similar relationship in the Soviet Union and estimated that Launch Complex J was two to three percent of the total cost of the program, meaning that the Soviet Union was probably spending between $10 and $18 billion on their new space program, clearly a large amount of money.

The large assembly building at Complex J. US intelligence analysts initially believed that the large rocket would be assembled vertically and rolled out to the pad. Eventually they concluded that it would be assembled and transported horizontally, like previous Soviet missiles and rockets. |

Waiting for Big Mother

What Sayre Stevens and his fellow analysts were waiting for was the giant launch vehicle that they thought would eventually appear at Complex J. But they had no hard data about this vehicle, which they started calling “the Big Mother.”

Stevens and his colleagues used the euphemism for years, until finally they were told by a superior that “Big Mother” was not a proper phrase for intelligence officials to use. “Somebody had complained,” Stevens explained with amusement.

In 1964 Stevens and his colleagues had speculated that the next big Soviet rocket might be a cluster of SS-8 ICBMs. “We looked frantically for a static test facility for the booster,” he explained. Satellite photos of the launch pads at Complex J indicated that the facility was robust, and might be capable of static testing the entire first stage. But the intelligence analysts were not convinced this was what the Soviets had decided to do. So they speculated that by clustering a bunch of smaller rockets together, the Soviets could skip the requirement for testing them all together on the ground.

By this time CIA analysts had forged close ties with NASA rocket and spacecraft experts and used them to assist in their assessments of the Soviet program. “I went to NASA and went to their booster expert,” Stevens said. The expert told him that a clustering approach would never work because there were so many problems associated with the interactions of all the thrust coming out of multiple engines that static testing was still required. Stevens dismissed the clustering hypothesis.

Throughout 1966, American satellites overflew the Soviet launch complex and took increasingly detailed photographs. The National Photographic Interpretation Center produced regular assessments of construction at the complex. Each individual satellite mission that flew over the facility resulted in a paragraph in a larger mission report. And in late 1966 NPIC produced what became an annual assessment of Complex J.

| Stevens and his colleagues used the euphemism for years, until finally they were told by a superior that “Big Mother” was not a proper phrase for intelligence officials to use. |

As a result of all this excellent photography rolling into NPIC, the agency had one of its model builders construct a series of three-dimensional scale models of the complex. He built two models of the entire launch pad area, and a conceptual model of the J1 pad, and a conceptual model of the J1 service tower and another model depicting the construction sequence for the service tower. These were useful tools for the analysts, but also excellent visual aids to show off when briefing senior leaders at the Pentagon and elsewhere.

Sometime during 1966 the continuing construction work at the launch pad caused the CIA analysts to increase their assessment of the size of the new Soviet launch vehicle. It is possible that they did this after seeing the size of the flame holes in the launch pad and guessing the diameter of the vehicle that would sit atop it.

In March 1967 the intelligence community produced an updated version of its National Intelligence Estimate assessment of the Soviet space program. Compared to the 1965 National Intelligence Estimate (NIE), the analysts had increased their estimate of the power of the Soviet booster. Whereas the 1965 document estimated the thrust at 22 million newtons (five million pounds), the CIA increased this estimate to 35 to 70 million newtons (8–16 million pounds), which was greater than the Saturn V’s 33 million newtons (7.5 million pounds), potentially twice as powerful. They speculated that such a rocket could use upper stages from the Proton rocket:

“If such a combination were to be launched initially by about mid-1968, it could be ready for manned space missions by about mid-1969. If the entire vehicle is new, however, and uses conventional propellants in all its stages (we define conventional propellants as those which have been used thus far in the Soviet launch vehicles), it could probably not be man-rated before 1970 at the earliest.”

Only a few months earlier, in January 1967, NASA had suffered its most devastating blow, with the deaths of three astronauts in the Apollo 1 fire. The recovery effort was still underway and NASA officials did not have a clear idea of when they would be able to attempt a Moon landing. Thus, any CIA estimate of Soviet lunar planning was more important than before.

The authors of the report concluded:

“[In NIE 11-5-65] we estimated that the Soviet manned lunar landing program was probably not intended to be competitive with the Apollo program as then projected, (i.e. aimed at the 1968-1969 time period). We believe this is probably still the case. There is the possibility, however, that depending upon the present Soviet view of the Apollo timetable, they may feel that there is some prospect of their getting to the Moon first and they may press their program in hopes of being able to do so.”

As construction proceeded at the two N-1 rocket launch pads, US intelligence satellites photographed the area and analysts drew illustrations of the facilities. |

The Jay-bird

A short time after NPIC had produced its 1967 annual report on Complex J, American reconnaissance satellites made a major discovery. Early in December 1967 a KH-8 GAMBIT-3 satellite photographed what NPIC photo-interpreters described as a very large transporter/erector, probably for use in handling the first and perhaps concurrently, second stages of the space booster to be launched from Launch Complex J. A December 1967 NPIC special report stated that the erector was first observed on the western pair of transporter tracks immediately north of the assembly building, but on the following day it was no longer there. NPIC conducted a detailed assessment of the size of the erector/transporter and noted that this would determine the maximum diameter of the stages of the launch vehicle it could carry.

But there was a bigger discovery in the photographs than the transporter: the Big Mother, the giant Soviet rocket, had finally appeared. It was photographed by both KH-8 GAMBIT and KH-4 CORONA satellites sitting on its launch pad. For instance, film taken on December 11 came back from CORONA Mission 1102-1 and the photo-interpreters saw a gleaming white object looking like a rifle bullet on the J1 launch pad. The CIA referred to it as “the J vehicle” in official reports, but according to one senior NPIC official, they usually simply called it “the Jay-bird.”

As construction proceeded at the two N-1 rocket launch pads, US intelligence satellites photographed the area and analysts drew illustrations of the facilities. |

The CIA, using a sophisticated device known as a Mann stereo-comparator, determined that the J vehicle was 102.1 meters (335 feet) tall. In reality, the actual length was 105.3 meters, which was remarkably close.

| The CIA referred to it as “the J vehicle” in official reports, but according to one senior NPIC official, they usually simply called it “the Jay-bird.” |

NPIC was not the only agency of the intelligence community with photo-interpreters. NPIC’s responsibility was for intelligence assessments of ground facilities. The actual missiles, submarines, ships or other weapons were analyzed by different agencies. Technical analysis of missiles was the responsibility of Air Force Systems Command’s Foreign Technology Division, or FTD, located at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio. No FTD reports on the J-vehicle have yet been declassified, although the results of their analyses clearly were incorporated into the NIEs.

As construction proceeded at the two N-1 rocket launch pads, US intelligence satellites photographed the area and analysts drew illustrations of the facilities. |

No smoking gun

Because Soviet missiles were a security threat to the United States, the intelligence community produced ballistic missile NIEs yearly. Space was less important. Soviet space efforts could embarrass the United States, but there was little direct threat from them, so the intelligence community produced space NIEs only every other year. But after the publication of the 1967 NIE, Soviet space activity increased and in April 1968 the CIA issued a “Memorandum to Holders” of its March 1967 National Intelligence Estimate. The seven-page update report noted that “In the year since publication of NIE 11-1-67, the Soviets have conducted more space launches than in any comparable period since the program began.” The report also stated:

“Considering additional evidence and further analysis, we continue to estimate that the Soviet manned lunar landing program is not intended to be competitive with the U.S. Apollo program. We now estimate that the Soviets will attempt a manned lunar landing in the latter half of 1971 or in 1972, and we believe that 1972 is the more likely date. The earliest possible date, involving a high risk, failure-free program, would be late in 1970. In NIE 11-1-67 we estimated that they would probably make such an attempt in the 1970-1971 period; the second half of 1969 was considered the earliest possible time.”

In other words, in mid-April 1968 the CIA had slipped back the date of the earliest possible Soviet lunar landing, making it all but certain that NASA—still recovering from the Apollo 1 disaster—would land there first unless NASA suffered another major setback.

| Back in November 1962 NASA Deputy Administrator Hugh Dryden had warned that it might not be possible to confirm that the Soviets had a manned lunar program until very late in the development phase. His foresight was prescient. |

CIA assessments of the Soviet manned lunar landing program continued throughout 1968 and 1969, reflecting the satellite imagery, and even became part of the congressional and public debate over Apollo. NASA Administrator James Webb mentioned Soviet rocket developments several times in front of Congress in 1967 and 1968. In August 1968 NPIC’s photo-interpreters spotted another “Jay-bird” on the launch pad and the next month NASA Administrator James Webb asked the CIA for permission to show photos of Complex J, and probably also the big rocket, to President Lyndon Johnson. The CIA did not object to Webb showing them to the President.

A February 1969 NPIC report noted that construction of the launch area was not yet complete. The report also stated that “In August and again in December a 335-foot missile was observed on Launch Pad J1.”

Back in November 1962 NASA Deputy Administrator Hugh Dryden had warned that it might not be possible to confirm that the Soviets had a manned lunar program until very late in the development phase. His foresight was prescient. For the next four to six years the intelligence community had been unable to find definitive proof that the Soviets were indeed planning on landing humans on the Moon, although the large rocket certainly appeared to be a major indicator.

Unfortunately, although significant intelligence documents have been released from this period, they still do not answer the question of when American intelligence estimates determined conclusively that the Soviet Union had a manned lunar landing program. The declassified National Intelligence Estimates from 1965 and 1967 indicate a shift in position toward the existence of a Soviet lunar landing program, but do not state why intelligence analysts reached this conclusion. It was not until 1969 that definitive proof became available, in the form of Soviet earth orbital tests of a lunar landing vehicle.

But by 1968 there was another big question to be answered: who would reach the Moon first, not to land, but simply to fly past or orbit it with a manned spacecraft.

Next: Part 3, The circumlunar program and winning the race.