A snapshot of MOL in 1968by John B. Charles

|

| These documents are interesting because they reveal the organization and implementation of a largely unanalyzed manned space program of the early Space Age. |

The Air Force started MOL in December 1963 as a general purpose orbiting laboratory to determine whether astronauts had any useful military role in space, but languished without authorization until August 1965. That is when the NRO agreed to incorporate its KH-10 DORIAN reconnaissance telescope into the program, but at a price: almost complete secrecy about the reconnaissance mission. Thereafter, budgets and content were either white (unclassified) if they originated from the Air Force or black (classified) if they originated from the NRO. When in doubt, secrecy prevailed.

The Air Force hoped MOL would grow into a continuing program of military man-in-space operations. Instead, it was cancelled in June 1969 without flying a mission, rendered obsolete by the rapid progress in unmanned reconnaissance satellites.

Over the decades, a lot of data about this secret program became available, but not a lot of information. The people behind it were reluctant to talk as long as the program remained classified. Finally, after a half century of secrecy, in October 2015 the NRO released the flood of documents, numbered chronologically at its website.

One of the most informative is number 521 in the NRO list, the MOL Flight Test and Operations Plan, dated May 8, 1968. Its 523 pages give a detailed overview of the MOL flight program, including management organizational structure, flight objectives, and ground support. It is a snapshot of planning for MOL three years before the scheduled date of the first launch, and describes a maturing—but not yet mature—program. Overall it probably reflects the eventual MOL flight program at least as well as a comparable document in 1965 would have described the actual Apollo flights.

Throughout the document, MOL is repeatedly described as a seven-flight program, all launched on the Titan-IIIM booster from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California. (The well-known Titan-IIIC test flight in 1966 that qualified the Gemini-B heat shield and did some additional MOL hardware tests was not included in this tally.) The first launch was to be a booster test carrying only a fairing ballasted to represent the Gemini-B/MOL payload. The second launch would have been the Gemini-B qualification flight, another suborbital test of the crew capsule in the flight environment including reentry, along with either an actual MOL or a full-sized MOL mockup, to verify launch vehicle compatibility. The third, fourth, and fifth launches would have been full-up manned missions labeled “manual/automatic” and the sixth and seventh launches were to be unmanned “automatic” missions.

The manual/automatic missions would have allowed comparison of reconnaissance effectiveness of those two operating modes, clearly intended to determine once and for all the usefulness of onboard human intervention. By 1968, unmanned reconnaissance satellites were beginning to demonstrate their critical value in the geopolitical security arena.

| The three manned missions would have been prepared in parallel, occupying 21 pilots—more than all of the pilots selected through 1969. |

The two unmanned missions would have replaced the Gemini-B with a structure holding six data return vehicles (DRVs), similar to the film-return “buckets” familiar from other unmanned reconnaissance satellites. The manned missions would not have carried any independent DRVs. Later documents, including number 800, the MOL program history, address the subsequent elimination of the automated flights from the program.

This document does not indicate the interval between launches, but another one, number 263, the monthly status report for May 1966, includes a summary chart that gives the interval between manned launches as three or four months:

- April 1969: Gemini-B qualification

- July 1969: structures test

- December 1969: manned automatic

- April 1970: manned automatic

- July 1970: manned automatic

- October 1970: automatic mode

- January 1971: automatic mode

The sequence was the same as in the 1968 plan, and each mission, whether manned or not, was scheduled to last a month.

Manning in general is thoroughly described. Not surprisingly for a highly visible military space program, there were a plethora of designated “directors” starting with the mission director, nominally the MOL program deputy director, and a cascade of flight directors. For example, the assistant flight director for crew operations was the crew communicator, a member of the pilot cadre.

Each manned mission would have involved six more of the pilots: two prime crewmembers, two alternates and two in support, with mission-specific training starting one year before launch. Thus, assuming three months between launches, the three manned missions would have been prepared in parallel, occupying 21 pilots—more than all of the pilots selected through 1969.

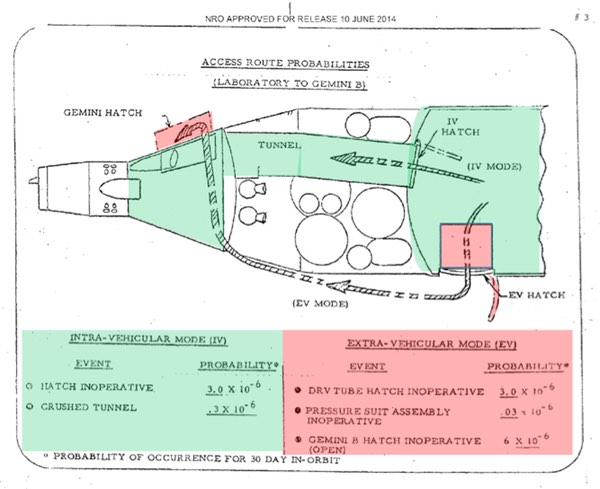

Contrary to popular supposition, extravehicular activities (EVAs) were anticipated only for contingency transfer if the tunnel between the Gemini-B crew capsule and the pressurized laboratory module was impassable. A major MOL experiment requiring EVA, the Astronaut Maneuvering Unit, had been transferred to the NASA Gemini program several years earlier. A word search of the document found only one other use of the term EVA: in the acronyms and abbreviations list at the end of the document.

MOL was to be launched due south into a low-altitude polar orbit. The “typical” launch date and time are given as April 4, 1971, at 21:00 GMT (1 pm Pacific Standard Time); this was presumably the first manned mission, which had slipped from its December 1970 scheduled date. Its orbit would have had a perigee of 148 kilometers (80 nautical miles) and an apogee of 344 kilometers (186 nautical miles), and would have been adjusted every three days to keep the perigee over the locations of interest.

| Contrary to popular supposition, extravehicular activities (EVAs) were anticipated only for contingency transfer if the tunnel between the Gemini-B crew capsule and the pressurized laboratory module was impassable. |

There were six remote tracking stations planned for use for MOL: New Hampshire, Vandenberg, Hawaii, Indian Ocean, Thule, and Guam. Only the California and Hawaii sites had been used during Gemini. The polar-orbiting MOL flights would have been highly autonomous due to the mostly equatorial locations of the ground stations. The high-latitude Thule station might have provided ground control for the de-orbit maneuver during the last northward pass of the mission, because the Gemini-B would have splashed down in the Pacific Ocean near Hawaii.

The MOL laboratory would have been deorbited into the ocean separately from the Gemini-B, in an unspecified but presumably remote location, to prevent retrieval of surviving components by an adversary.

These are only a few of the insights available in this document, cherry-picked from the flight test objectives, operations organization and responsibilities, launch operations, flight operations, recovery operations and crew operations sections. More revelations wait in the training, simulation and operational readiness, flight test constraints, flight test data evaluation, and crew operations and interfaces sections, and in the hundreds of other documents now available to serious researchers and armchair historians.