NASA’s Journey to Mars and ESA’s Moon Village enable each otherby Vid Beldavs, Bernard Foing, David Dunlop, and Jim Crisafulli

|

| When the space economy becomes self-sustaining, profits from operations on the Moon and in cislunar space will become sufficient to sustain continued operation. Further development will no longer be dependent on government subsidies from Earth. |

Key to opening a frontier is the capacity to “live off the land” for in situ resource utilization (ISRU). There would have been no pioneers on the American frontier if they had to carry everything with them. Activities in space will remain limited to exploration until ISRU becomes possible on an industrial scale. ISRU and the mining and use the resources of the Moon, asteroids, comets, and other celestial bodies enables the opening of the space frontier for permanent occupancy and settlement. The capacity for ISRU creates the basis for a space economy where products and services are traded for resources, increasingly sophisticated products can be produced from mined resources, and life can be sustained indefinitely.

When the space economy becomes self-sustaining, profits from operations on the Moon and in cislunar space will become sufficient to sustain continued operation. Further development will no longer be dependent on government subsidies from Earth. This is not to say that government investment in space would cease. Most likely commercial successes will drive increased government investment. As government investment results in improved infrastructure and better technologies, and thus costs and risks drop, more opportunities will appear for more participants. Government investment will continue to be required for planetary science and other space related research, to train and develop people (human capital), and to develop and maintain infrastructure. These are accepted roles for government investment on Earth and can be expected to continue in space. But it is also clear that we will remain Earth-bound as long as the taxpayer has to pay all the bills for space activities.

Framework for international collaboration

ILD is intended to provide a framework for international collaboration to achieve a self-sustaining space economy and the opening of the space frontier. After breakthrough to a self-sustaining space economy is achieved, further commercial investment will drive measureable growth in economic output from space activities, just as increased investment drives increased output on Earth. Before that breakthrough is achieved, continued investment accumulates as losses. Losses have discouraged private investment in space ventures except by the super-wealthy, who can sustain significant losses for long-term gains.

Important for the success of ILD will be development of investment funds and financing mechanisms that enable space entrepreneurs who are not super wealthy to develop high potential ideas that require a long time to positive cash flow. Private-public partnerships such as Commercial Transport and Commercial Crew are highly promising and play a prominent role in the Lunar COTS proposed by Zuniga et al. Some strategic elements, such as a lunar power utility, may not lend themselves to a private-public partnership approach, as the availability of sufficient power to drive other ventures is required early, but the returns on investment may not come until after 2030 when significant ISRU operations get underway. A utility type of financing may work best there (see “The lunar electrical power utility”, The Space Review, November 9, 2015). There are compelling reasons to consider the development of a space investment fund linked to government guarantees that can leverage private-public partnership approaches when available.

| Self-sustaining space economies are a necessary element of planetary defense strategies to assure species survival beyond Earth. |

It is extremely important to understand the gains that will come with the breakthrough to a self-sustaining space economy. At that point, more common financing mechanisms and sources of capital will start to play a role. The cost of capital will decrease and the returns to capital will come faster. All players involved in the game of space whether entrepreneur or space scientist will benefit from a strategic approach to achieve a breakthrough to a self-sustaining space economy.

In the long term, self-sustaining space economies such as colonies on Mars could operate largely independent of inputs from Earth. Self-sustaining space economies are a necessary element of planetary defense strategies to assure species survival beyond Earth.

Creating the International Lunar Decade

Werner Von Braun, Krafft Ehricke, and Gerard K. O’Neill were among giants in the field with well-articulated visions of space industrialization. Major shifts in US space policy and global developments, though, dashed plans for their realization. The 2004 Vision for Space Exploration of the Bush Administration proposed the idea of reaching Mars with utilization of lunar resources. In this timeframe the International Space Exploration Coordinating Group (ISECG) and the International Lunar Working Group (ILEWG) were formed. A vision for an International Lunar Decade was raised in 2006 by the Planetary Society and endorsed by COSPAR at the Congress in Beijing as well as by ILEWG at their meeting July 23-27, 2006. As US policy changed with a new administration, and the economic crisis took a toll on space budgets around the globe, the idea of a highly visible global lunar initiative faded. However, the space agencies involved through ILEWG continued to work to complete the agenda of missions set in 2006 and to further the Global Exploration Roadmap developed by ISECG.

ILEWG continued its activities and new ideas were put forth by Russell Cox, who proposed an International Lunar Geophysical Year (ILGY) beginning in 2017—the 60th anniversary of the International Geophysical Year (IGY)—at the 2012 Lunar Exploration Analysis Group meeting. Russell, Pam Clark, and David Dunlop made several presentations in support of an ILGY Campaign at conferences from 2013 through 2015.

Preparation for ILD in its present form started with the International Lunar Decade Declaration at the conference The Next Giant Leap: Leveraging Lunar Assets for Sustainable Pathways to Space held in November 2014 in Hawaii. In 2015, ILD proponents made presentations at a series of conferences, most recently by the International Lunar Exploration Working Group with the Moon Village Workshop at ESA/ESTEC in December.

Numerous activities are getting underway in 2016, building towards the launch of ILD in 2020. First on the Agenda is the meeting of the Scientific and Technical Subcommittee of the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS), where the National Space Society has been invited to present the ILD vision. Several other conferences will feature presentations and sessions on ILD in 2016, including several Moon Village workshops planned by ESA. Of particular importance are the Lunar Workshops being organized by ILEWG before and at the COSPAR General Assembly in Istanbul July 30 – August 7.

| We are now at the dawn of a new space age with the prospect of opening opportunities for benefits from space exploration and space industrial and commercial development to millions of additional people. |

Building up to the launch of ILD will be major celebrations of the dawn of the space age in 2017 marking the 60th anniversary of the IGY and the launch of Sputnik as well as the 50th anniversary of the Outer Space Treaty that came into force in 1967. IGY inspired the first global collaboration in research to better understand our planet and our place in the universe. The legacy of IGY is a host of collaborative research networks that have yielded the science to understand the global impact of climate change. IGY-inspired research and related technology development was also a major factor in the rapid global economic development that followed, which has lifted hundreds of millions of people worldwide out of poverty.

We are now at the dawn of a new space age with the prospect of opening opportunities for benefits from space exploration and space industrial and commercial development to millions of additional people. It is therefore fitting to call this period, including the International Lunar Decade, the “opening of the space frontier” that will enable ISRU and make possible permanent human settlement beyond the Earth. During the preparatory time from 2017 to 2020, collaborative relations will be strengthened among spacefaring nations in readiness for the launch of the ILD now expected to take place on July 20, 2019, commemorating the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11, when Neil Armstrong spoke of the “one giant leap for mankind.” The next giant leap will take more than a decade.

What is possible by 2030

An International Lunar Decade that results in the achievement of a self-sustaining lunar economy can achieve a great number of things in just ten years:

Lower costs: The cost of delivering payloads to the surface of the Moon will be less than current costs of launching payloads to low Earth orbit (LEO). Progress in lowering the cost of launch to LEO, as demonstrated by the potential for reusability recently demonstrated by SpaceX and Blue Origin, can be expected to continue to be augmented by further reductions in costs due to ISRU, alternative propulsion methods, and continued technological advances, as well as efficiencies gained through systemic effects and higher launch rates.

Reliable electrical power: A lunar power and communications and utility will provide electrical power, broadband communications, and navigation services to anywhere on the lunar surface and in lunar orbit.

ISRU: Lunar ice, lunar regolith, and other resources will be mined to provide fuel, materials for construction on the Moon and in space, radiation shielding, and other uses for spacecraft heading to Mars or other deep space missions.

Opportunities for science: This includes research of, on, and from the Moon, including teleoperations of surface robotic elements, building on missions and results from previous lunar decade of orbiters, and preparing for human-robotic partnerships.

Platforms and fuel depots: These will be under development in LEO and at Earth-Moon Lagrange points and provide habitats and facilities for research, assembly, manufacturing, and staging operations that enable continued reductions in costs, lower risks, and expansion of opportunities building on capabilities achieved on the ISS.

Asteroid mining: The potential for asteroid mining will be significantly expanded as a result of the infrastructure and industrial development underway on the Moon and in cislunar space.

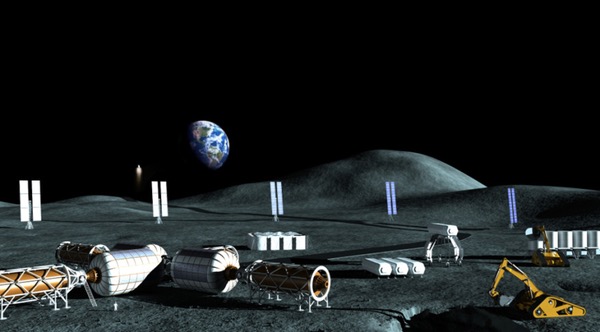

Moon Village: The Moon Village vision of ESA Director-General Jan Wörner will have evolved through an initial purely robotic phase (the “Lunar Robotic Village” endorsed by ILEWG), to a polar human base with access to the lunar farside that can accommodate 10 people effectively, with work underway to facilities for 50 or more permanent occupants.

Human Mars mission: The prospects for human missions to Mars (in the spirit of a “Mars Village” with broad international collaboration) will be significantly enhanced through the substantial reduction in costs and expanded capabilities made possible by infrastructure and “proving grounds” in cislunar space and on the lunar surface, particularly as a result of the beginning of lunar industrial activities.

ISS and successors IN LEO/E-ML1/E-ML2: These outposts will continue to serve a vital role as research platforms for medical studies, space manufacturing, assembly platforms, and hotels for the emerging space tourism industry.

Leading roles

NASA has made it clear that it is focused on reaching Mars and therefore cannot assume leadership of a major international program to return to the Moon. However, NASA administrator Charles Bolden has offered NASA support to international partners as well as private business involved in lunar development.

| The NASA “Lunar COTS” strategy, combined with ESA’s Moon Village strategy, can accelerate both reaching Mars and exploring and developing the Moon and cislunar space. |

The broader US space strategy covering both government space exploration and commercial space development in no way excludes lunar operations. Several companies have already been formed to provide transportation to the Moon as well as for ISRU and energy production. The new U.S. Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act opens greater opportunities for asteroid and lunar mining, although the issue of property rights remains unresolved in the international context.

NASA planning includes use of private public partnerships and other instruments to lower the cost of reaching Mars. This NASA “Lunar COTS” strategy, combined with ESA’s Moon Village strategy, can accelerate both reaching Mars and exploring and developing the Moon and cislunar space.

ESA Director-General Jan Wörner envisions ESA taking a central role for lunar exploration and development. The focus of ESA’s efforts is the “Moon Village” that could be seen as a polar and or farside Moon base, or something much more. Wörner is inviting prospective partners to participate in Moon Village development in an open, bottom-up process aimed at incorporating research and other interests into the emerging architecture of the “village.” There is no top-down master plan. ESA’s approach is to incorporate the interests and the contributions of international partners, including space agencies, research centers, and private companies, in the design and architecture of the Moon Village. In the coming months, a series of workshops are planned to engage researchers, students, artists, and business people in generating ideas, based on the workshop last month.

As the Moon Village emerges through multiple missions such as Luna 27 (a joint ESA- Russia lunar landing near the ice deposits at the lunar south pole), businesses will be encouraged to identify revenue-generating services that can be financed through public-private partnerships modelled on NASA’s commercial cargo and crew programs, where government requirements form the initial market and government provides a share of the investment to launch the business. Companies are already eyeing ISRU opportunties through which NASA could purchase water for fuel, life support, and radiation shielding to lower the cost of reaching Mars.

The Moon Village will require energy and broadband communications, while lunar rovers will require navigation support. These services could be provided by a lunar power and communications utility. We have proposed that this could be a role for private business, potentially in partnership with a consortium of electrical power utilities serving markets on the Earth. The advantage to the utilities would be that they could pilot space-based solar technologies for later application to power generation to meet the needs of their customers on Earth.

Key roles will be played by ISECG and ILEWG to coordinate the activities of the increasing number of countries and entities including private businesses and university research involved in lunar exploration and development.

Engaging other international partners

Russia, China, India, South Korea, Japan, and other spacefaring countries are planning missions to the Moon. Coordinated with NASA plans to reach Mars, the interests of all parties can be met more fully than if they acted separately.

Uncertain international conditions and economic stress are strong arguments for international collaboration in space exploration and development. However, unstable condtions can also make it more difficult to collaborate. This argues for the adoption of a general framework for collaboration towards a general goal over a longer span of time. Consensus can be achieved on an overarching general goal with specifics negotiated over a longer span of time where consensus is more difficult to achieve. The promise of the International Lunar Decade is that it is fully consistent with the Mars strategy of NASA and the Moon Village vision of ESA. ILD also offers Russia, China, and other prospective partners that may be experiencing economic stress the opportunity to more fully realize their space goals both as part of the Moon Village and as contributors to the challenge of reaching Mars.

The European Union already collaborates with almost every UN member state at some level. The EU Horizon 2020 R&D funding scheme has cooperative programs with the US, China, Russia, India, Brazil, South Korea, Japan, and many other nations generally with cost sharing by other advanced nations to cover expenses incurred by participants from these nations. Horizon 2020 also provides funding to researchers from Africa and other developing countries purely on a competitive basis with no requirement for cost sharing by the developing country. Horizon 2020 already includes funding for space related R&D. Given engagement of the EU in the ILD process, the development of enabling technologies could be advanced through competitive calls using the Horizon 2020 administrative processes.

Role for prizes

The Google Lunar X Prize has engaged teams from many countries to meet the challenge of landing on the Moon, covering 500 meters across the lunar surface and broadcasting high-resolution images of the achievement. Sixteen teams remain registered for the competition. While it has proven far more difficult to achieve the prize goal than anticipated, the competition has stimulated considerable innovation and demonstrated the potential for groups not funded by governments to reach the Moon. During the course of the ILD, numerous other challenges present themselves as opportunities for prizes to drive technology development and achievement beyond what would be otherwise thinkable. Who will win the prize for the first rover circumnavigating the Moon at its equator? Or who will be the first to process one ton of regolith into its constituent materials?

Moon Village governance and policy issues

The creation of the Moon Village creates the need for governance and conflict resolution mechanisms as well as decision processes for policy formulation. This raises the possibility of a compromise between those that see treaty-based processes as too cumbersome to address the dynamic needs likely to arise on the Moon and elsewhere, and those that advocate for a treaty-based approach centered on the Moon Treaty and the international regime for lunar development anticipated by that treaty. The Moon Treaty has been ratified by only 16 states, of which none are spacefaring powers, and is therefore widely considered as a failed treaty that is inactive. The Moon Treaty has strong opposition from those that see it as counter to private enterprise in space. However, France and India have signed and are spacefaring powers, and several of the ratifying countries are planning lunar missions, such as Mexico. Opposition to the Treaty centers on the doctrine of the “Common Heritage of all Mankind” and the specific exclusion of ownership of property as specified in Article 11, par. 3:

Neither the surface nor the subsurface of the moon, nor any part thereof or natural resources in place, shall become property of any State, international intergovernmental or non-governmental organization, national organization or non-governmental entity or of any natural person.

Of particular relevance to lunar development is Article 11, paragraph 7 that outlines the basic principles to guide formulation of an international regime to govern lunar development:

7. The main purposes of the international regime to be established shall include: (a) The orderly and safe development of the natural resources of the moon; (b) The rational management of those resources; (c) The expansion of opportunities in the use of those resources; (d) An equitable sharing by all States Parties in the benefits derived from those resources, whereby the interests and needs of the developing countries, as well as the efforts of those countries which have contributed either directly or indirectly to the exploration of the moon, shall be given special consideration.

The Moon Treaty provides a process to negotiate an international regime to govern lunar development. If major spacefaring powers do not choose to ratify the Moon Treaty, an alternative process will be required to determine mining rights and other matters necessary to conduct business on the Moon. The participants in the Moon Village, in principle, could reach agreement among themselves on these matters. As long as what is agreed to does not violate the Outer Space Treaty that has been ratified by most countries, agreements reached by the participants in the Moon Village would also have the force of law and, if consistent with Article 11, paragraph 7 of the Moon Treaty, would in spirit be consistent with an international regime that could have resulted from negotiations among the States Parties to the Moon Treaty. If negotiations among parties to the Moon Treaty cannot result in a satisfactory “international regime” in a reasonable time to meet the needs of companies already operating on the Moon as members of the Moon Village, the agreements among the participating entities in the Moon Village could become customary law governing lunar development.

In principle, a Moon Village council that represents all participants could make decisions regarding matters such as determining the technical parameters of defining resources located on the Moon. Such a council could also develop transparent, competitive processes to determine which company or organization would have rights to engage in activities that may have an impact on other participants.

| NASA’s Mars strategy is highly complementary to ESA’s Moon Village vision. Both augment each other such that without NASA’s Mars mission settling the Moon Village will be far more challenging. |

For example, a lunar landing site could create dust problems for an observatory, requiring that either the observatory or the landing site be located elsewhere. There are purely technical requirements as well as requirements that affect the Moon Village and its survival and further development. In the process of developing the Moon Village, the participants could invest such a Moon Village council with authority to make a range of decisions based upon guiding principles agreed to by the states participating in the village. The decisions of such a council, along with their guiding principles negotiated among the participating nations, would form a body of normative acts that govern the village. These governing acts would draw from the actual experience of the participants, rather than be defined in the abstract by parties with no direct involvement and with agendas that may be counter to the development of space.

Conclusions

NASA’s Mars strategy is highly complementary to ESA’s Moon Village vision. Both augment each other such that without NASA’s Mars mission settling the Moon Village will be far more challenging. Concurrently the Moon Village through its development and operation serves to address key issues facing NASA particularly the development of infrastructure and enabling technologies for ISRU as well as creating mechanisms for joint decision-making, coordination, conflict resolution and the creation of long term financing instruments for space development.