Future telescopes versus telescopes’ futuresby Jeff Foust

|

| “The spacecraft health is very good,” Troeltzsch said of Kepler, now on its “K2” mission. |

Those telescopes will, over the next couple of decades, build upon the discoveries made by earlier observatories in space and on the Earth. Some of those facilities, though, face an array of challenges: technical, financial, and even political. Astronomers that have come to rely on space-based telescopes wonder how long those facilities will last, while ground-based observatories, existing and planned, struggle to find funding and win necessary approvals to operate.

Extended, extended missions

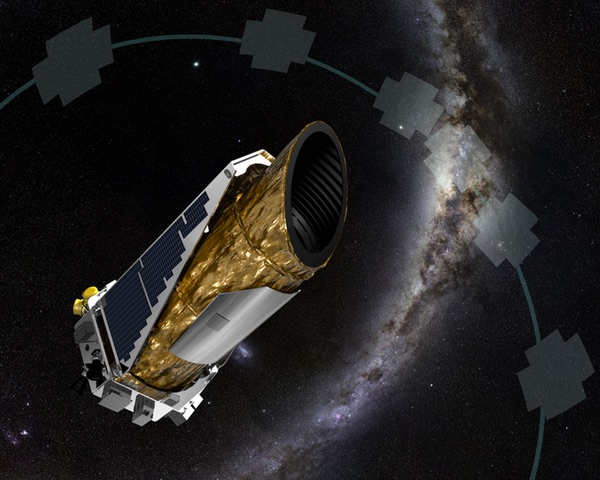

NASA’s Kepler mission died—and lived to tell the tale. In 2013, the second of four reaction wheels on the spacecraft failed, preventing the spacecraft from pointing at the same field of the sky it had since its launch in 2009. That ended the spacecraft’s primary mission of staring that that same field, looking for minute, periodic decreases in brightness of stars caused when exoplanets crossed in front of them, a technique known as transit photometry that has been used to discover thousands of exoplanets.

The project instead proposed an alternative mission, known as “K2”. Instead of looking at the same field of the sky continuously, Kepler would look at a series of fields for about 80 days at a time, dubbed “campaigns,” using the two remaining reaction wheels, plus thrusters and solar pressure, to keep the spacecraft accurately pointed. NASA accepted that proposal in 2014, and the K2 mission got underway shortly thereafter (see “Two astronomy missions back from the brink”, The Space Review, January 12, 2015).

The K2 mission continues without any major technical problems. “The spacecraft health is very good,” said John Troeltzsch of Ball Aerospace during a town hall meeting about K2 at the AAS meeting. There have been few spacecraft issues disrupting observations. “When we’re not downloading data, we are taking science data,” he said.

Project officials are confident that performance can continue at least for the next couple of years. Communications, as the spacecraft drifts farther away from Earth, and propellant for its thrusters are the key limiting factors on its longevity. “We’re in good shape to get out to Campaign 17,” he said, referring to observations planned for early 2018.

The shift to the K2 mission has changed some of the science. The original Kepler mission, staring at the same part of the sky for years, was intended to provide an estimate on the fraction of stars that have “Earthlike” planets, at least in the sense of those planets’ sizes and orbits. That’s not possible with K2, where the spacecraft looks for less than three months at one region of the sky.

K2, though, has opened up new avenues of research. “We’re very different than Kepler,” said Tom Barclay, director of the K2 guest observer office. With the original Kepler mission, he notes, “we were almost entirely focused on exoplanets. With K2, that’s not the case. We’re a very different mission.”

Barclay noted that K2 proposals have focused on a wide array of topics, from studies within our solar system to stellar astrophysics. Only about 30 percent of the guest observer programs, he said, are devoted to exoplanet studies. “They’re still an important part for us, but it’s really not the biggest area of our research. Stellar astrophysics is really catching up.”

K2 is still finding new exoplanets. In presentations at the AAS meeting, astronomers discussed some early results from analyses of the first few campaigns of K2 data. Andrew Vanderburg of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics reported detecting 234 planet candidates around 208 stars in data from K2’s first year. Ian Crossfield of the University of Arizona announced the discovery of more than 100 “validated” exoplanets, after additional analysis to remove false positives.

“This is a validation of the whole K2 program: its ability to find large numbers of true, bona fide planets,” Crossfield said in his talk.

| “We have an obligation to make sure that the Hubble mission is completed safely,” Hertz said. |

K2’s biggest obstacle to further exoplanet studies and other science may be more fiscal than technical. It, and other NASA astrophysics missions that have exceeded their primary missions, are subject to a “senior review” this year where NASA will balance those missions’ science plans with their costs and available funding. Proposals by K2 and seven other missions were due to NASA last Friday, with a final decision by NASA expected in May or June.

Another of those missions involved in the senior review is the Hubble Space Telescope. However, there is no doubt that Hubble will continue operating beyond 2016, and it, along with the Chandra X-Ray Observatory, will be treated separately from the other six missions in the astrophysics senior review.

Hubble, which marked its 25th anniversary last year (see “On Hubble’s 25th, looking at the next 25 years”, The Space Review, April 27, 2015), has gone through challenges that make Kepler’s problems look mild by comparison. A series of servicing missions helped to both repair and upgrade the orbiting observatory, but the last of those was in 2009.

Scientists remain confident that Hubble still has several more years of life left in it. “We do believe that Hubble is in good, healthy technical shape, and so we think we have quite a few years yet to go,” said Jennifer Wiseman of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in an AAS talk. How many years? “Hopefully for some years beyond 2020.”

That optimism is reflected in long-term NASA planning. At a NASA town hall meeting during the conference, Paul Hertz, director of NASA’s astrophysics division, showed a 20-year budget “sand chart” that projected spending on the division’s various programs out through the mid-2030s. That chart, intending the show available funding for both upcoming missions like JWST and WFIRST as well as “future strategic missions” beyond it, included a line for Hubble out to fiscal year 2025.

At the town hall, some attendees asked about a different budget line that started around fiscal year 2030, running through 2035: “HST Completion.” What’s that?

That notional funding, Hertz said, is for a future robotic mission to safely dispose of the space telescope once its mission ends. “We have an obligation to make sure that the Hubble mission is completed safely,” he said, since much of the spacecraft would survive an uncontrolled reentry into the Earth’s atmosphere and reach the surface.

That mission, he said, could be a controlled reentry of Hubble, or a move into a higher, longer-lived orbit. “At some point in the future, we’re holding a plan to move Hubble into a safe place,” he said. “Hubble has a long, productive lifetime in front of it before we ever have to worry about that.”

The NSF is looking for partners who can take over some or all of the operations of the Arecibo radio observatory in Puerto Rico. (credit: NSF) |

Arecibo’s fate

Long before Kepler or even Hubble made it into space, astronomers have relied on the Arecibo radio observatory. The radio telescope’s dish, fitted into the Puerto Rican landscape, is 305 meters in diameter: the largest in the world since it opened more than 50 years ago.

That record will soon be eclipsed, though. The Five hundred meter Aperture Spherical Telescope, or FAST, is under construction in China and, as its name indicates, features a primary dish 500 meters across. FAST is slated for completion later this year.

Astronomers, though, are more worried about how much longer Arecibo will continue to operate. Last fall, the National Science Foundation (NSF), which provides about two-thirds of the funding for Arecibo operations, issued a “Dear Colleague” letter soliciting proposals from organizations willing to shoulder some or all of the cost of the radio telescope.

| “Our worst outcome would be not to have it continue to do great science,” the NSF’s Knezek said of Arecibo. |

That letter is part of a broader “divestment strategy” by the NSF’s astronomical sciences division to reduce the fraction of its modest budget—less than $250 million per year—devoted to operating telescopes versus funding research that uses them. Without that divestment, and with flat budgets expected to continue, the share of NSF spending going to observatory operations would continue to grow as new facilities came online, squeezing funding for research.

Various options for divesting observatories range from partnerships with other organizations to decommissioning. “Partnerships are preferred, but they’re complicated and they require funding from someone,” said James Ulvestad, director of NSF’s astronomical sciences division, at an NSF town hall meeting during the AAS conference.

In the case of Arecibo, a decision of some kind about its future will come soon. The cooperative agreement to operate Arecibo with a consortium that includes SRI International, Universities Space Research Association, and Universidad Metropolitana, a Puerto Rican university, ends at the end of this fiscal year. Responses to the Dear Colleague letter were due to the NSF in mid-January.

Ulvestad noted that any decision on divesting Arecibo is complicated by how it’s funded. NSF funding for the observatory is split between its astronomical and geosciences divisions, while NASA provides the remaining funds to support planetary radar work, using the radio telescope to observe passing asteroids to characterize their shape.

Further complicating Arecibo’s future were claims last year that a private foundation, Breakthrough Initiatives, offered to help pay for Arecibo operations in exchange for a share of its observing time that would go towards its Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) effort, Breakthrough Listen. One Arecibo official claimed that he was told by the NSF that its government funding would be jeopardized if it accepted any private funding.

NSF officials denied that, and noted that Breakthrough Listen is funding part of the operations of the Green Bank Telescope, another radio observatory included in the NSF’s divestment plan. They did not rule out that Breakthrough Listen could play a role in any future operations of Arecibo.

At a meeting during the AAS’ Division for Planetary Sciences conference in November near Washington, DC, NSF officials emphasized they wanted to find some way to keep Arecibo open. “Our worst outcome would be not to have it continue to do great science,” Patricia Knezek, deputy director of the NSF’s astronomical sciences division, said at the time.

Construction of the Thirty Meter Telescope, illustrated above, remains on hold after a Hawaiian court revoked a construction permit because of a “procedural mistake” made by the state. (credit: TMT) |

TMT timeout

Another groundbased observatory is also facing an uncertain future, even though it hasn’t even been built yet. Construction of the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT), an observatory with a primary mirror 30 meters in diameter, was scheduled to begin last spring near the summit of Maunakea, Hawaii. However, a group of protestors, primarily native Hawaiians who believe the observatory would desecrate what they consider a holy site, blocked the road to the summit, putting construction on hold (see “Thirty meter troubles”, The Space Review, July 6, 2015).

In December, the TMT suffered another setback. The Hawaiian Supreme Court ruled that the state’s Board of Land and Natural Resources improperly granted a construction permit for the observatory without taking into account opposition to the permit. The court invalidated the permit and instructed the board to hold a new “contested case” hearing on the issue before deciding whether to reissue the permit.

The future of TMT has been in limbo since. “We are assessing our next steps on the way forward,” Henry Yang, chairman of the TMT International Observatory Board, said in a statement shortly after the court’s ruling.

| “The project is now pursuing the process that needs to happen in order to get the permit to begin construction” of TMT, Harrison said, after a court revoked the original permit. |

Questions about the TMT’s future—and, perhaps, the promise of free food and drinks—attracted a standing room only crowd of astronomers to a TMT town hall meeting during the AAS conference. Astronomers involved in the TMT, though, could offer only vague assurances that the project will continue in some form and at some time.

Fiona Harrison, a professor of astronomy and chair of the physics, mathematics, and astronomy division at Caltech, one of the universities involved in TMT, described the court’s decision as the result of a “procedural mistake” by state officials in the permitting process. “This was a mistake made not by the project but a mistake made by the state of Hawaii,” she said.

Harrison emphasized the importance of continuing TMT atop Maunakea. “The project is now pursuing the process that needs to happen in order to get the permit to begin construction,” she said. The project, she said, is awaiting “definitive statements” from Hawaii’s governor and attorney general before making any specific decisions.

TMT project leadership, though, is assuming that they will not be able to begin construction any time soon. Harrison’s slides noted that the project is “undergoing a replan that does not include activities at the summit for at least one year to minimize effects of delay and understand the ramifications” of the court’s decision.

At the town hall, officials described other work that was going on around the world with TMT, including polishing of mirror segments and development of the initial suite of instruments for the observatory. Officials also emphasized that, despite the considerable media attention the protests They TMT received last year, most Hawaiians support the observatory’s construction.

A new poll published last week supports that claim. The poll, conducted for the Honolulu Star-Advertiser, found that 67 percent of registered voters support construction of TMT, versus 27 percent who oppose it. Among native Hawaiians only, though, the numbers are nearly flipped: 59 percent oppose TMT, while 39 percent support it.

That suggests that, even if TMT decides to proceed with construction of the observatory on Maunakea and receives a new permit from the state, the project will continue to face obstacles from those opposed to its construction.