The unfortunate provincialism of the space resources actby Thomas E. Simmons

|

| It seems likely that the first extraterrestrial property dispute to erupt will be one between a US company enjoying the blessing of the Department of Transportation and a non-US company, with or without asteroid mining authorization from its country of origin. |

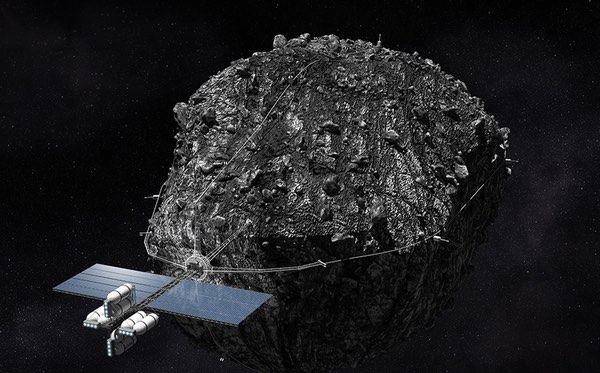

The most likely commercial activity beyond Earth orbit in the near future is the mining of asteroids: Deep Space Industries and Planetary Resources (both American companies) have already announced their intentions to do so.2 So long as commercial parties voluntarily stay out of each others’ ways with their asteroid mineral extraction enterprises, property rights in the minerals will go unchallenged.

Some scholars have questioned whether the licensing of off-planet mining violates the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, to which the United States is a signatory.3 Yet even if, for example, Deep Space Industries’ ownership of a few metric tons of asteroid-sourced titanium might be questioned on these grounds, once the company achieves initial and exclusive possession of the minerals, no other party or person would have adequate standing to challenge its ownership without any co-extensive or prior claim. In other words, after an unmolested extraction of asteroid minerals, even if another company could challenge ownership of the minerals by referring to the Outer Space Treaty, it would lack any motivation to do so since, even if it prevailed, it would not result in the challenger owning the minerals either. Any rival American company’s claims to the same asteroid’s minerals would have been sorted out through the Department of Transportation’s licensing framework.

Therefore, it seems likely that the first extraterrestrial property dispute to erupt will be one between a US company enjoying the blessing of the Department of Transportation and a non-US company, with or without asteroid mining authorization from its country of origin. The Space Resource Exploration and Utilization Act sadly lacks any mechanisms for avoiding or resolving this kind of dispute. Without a legal framework for dispute resolution, an inefficient “first to grab” methodology in outer space may become the norm between US-based companies and companies from the rest of the world. The “first to grab” method arguably benefits US companies so long as they outpace the rest of the world, but as other countries’ technological reach catches up, commercial inefficiencies and profit loss would soon be the price for embarking on such a selfish trajectory.

The principal shortfalls of the Space Resource Exploration and Utilization Act are twofold. First, only US citizens or companies can claim ownership rights to asteroid minerals by virtue of the Act.4 Second, Congress missed the opportunity to give recognition to extraterrestrial mineral extractions carried out under the authority of a reciprocating nation’s laws, as it did with commercial exploitation of the deep sea bed.5

The United States should position itself as a world leader in the commercial exploration and recovery of asteroid mineral resources. Instead, it has adopted a narrow and arguably arrogant assumption that only US companies will participate in asteroid mining. As a result, the certainty of property rights that is essential to the enormous capital investments necessary to begin asteroid mining is compromised. A US company’s rights to carry out mining on a particular asteroid are only secure so long as its competitor is another US company. When a non-US company enters the picture, the outcome is uncertain.

Instead, Congress should have authorized the Secretary of Transportation to license non-US citizens and companies and recognize the property rights of licensed companies, whether domestic or otherwise, which explore and extract asteroid minerals in conformity with their licenses. Establishing a rulebook for licensing non-US companies would undoubtedly task the Department of Transportation with a wide set of challenges, and non-US companies may choose to simply avoid seeking authority from the US government before embarking on an asteroid mining venture. But if the US postures itself as a fair, efficient, and unbiased mediator of asteroid mining rights, non-US companies may, in fact, voluntarily participate in a licensing system under American law. The availability of adjudicating property disputes in US courts or before US administrative bodies could be seen as economically attractive if those forums are seen as providing efficient and predictable outcomes, or at least more fair and rule-bound than their own country’s alternatives.

| The common interest of commercial enterprises in all countries would suggest the development of international customs, if not international treaties, which give effect to these kinds of limitations. |

Even if non-US companies elect governance and licensing solely under their own countries’ administrative bodies, Congress should amend the act to give recognition to asteroid mining licenses granted by other nations as it did in the Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act.6 US companies will not directly benefit from a US law that requires them to abide by rights granted to competing companies by virtue of other nations’ licenses. Indeed, it might be anticipated that some countries’ administrative bodies would simply grant blanket rights to unreasonably large numbers of asteroids—or even the entire asteroid belt—as, for example, equatorial countries have attempted to do with regards to geostationary orbits.7

What would likely develop from this kind of “claim jumping” would be US regulatory responses that limit the Secretary of Transportation’s recognition of non-US asteroid mineral rights to ones that are commercially exploitable or those reduced to actual extractions within a reasonable period of time. The common interest of commercial enterprises in all countries would suggest the development of international customs, if not international treaties, which give effect to these kinds of limitations. Recognized customs drive the development of international law as much as negotiated treaties. If the US is willing to grant recognition to other countries’ licensing authorities, it would put the world on a path to developing these kinds of customs, gradually solidifying into recognized principles. With the narrow reach of the current legislation, however, such customs are must less likely to develop. A long view of asteroid mining merits thoughtful tweaks to the act.

Endnotes

- US Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act, Pub L. 114-90, 129 Stat. 704 § 101 (2015) [hereinafter, the “Space Act”].

- Stephen Dinan, “Congress Oks Space Act, paves way for companies to own resources mined from asteroids”, Washington Times (Nov. 16, 2015).

- See Gbenga Oduntan, “Who owns space? US asteroid-mining act is dangerous and potentially illegal”, The Conversation (Nov. 29, 2015) (claiming the Space Act “represents a full-frontal attack on settled principles of space law”). Congress attempted to conform the Space Act to the Outer Space Treaty as evident in the legislation’s statement that Congress sensed “that by the enactment of this Act, the United States does not thereby assert sovereignty or sovereign or exclusive rights or jurisdiction over, or the ownership of, any celestial body.” Space Act § 403.

- Space Act § 402 (to be codified at 51 U.S.C. § 51303).

- See 30 U.S.C. § 1411(c) (prohibiting US citizens and companies from interfering with the recovery of hard mineral resource exploration or recovery of those conducted by the holder of an “equivalent authorization issued by a reciprocating state”). A “reciprocating state” under the Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act means a foreign nation designated by the Administrator of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.” 30 U.S.C. § 1403(11).

- 30 U.S.C. ch. 26.

- Michael J. Finch, “Comment, Limited Space: Allocating the Geostationary Orbit”, 7 Nw. J. Int’l L. & Bus. 788 (1986).