A starshot into the darkby Jeff Foust

|

| “How do we go faster? How do we go further? How do we make this next leap?” Milner asked. |

The latest to put his money into space ventures is Russian billionaire Yuri Milner, who made his money thanks to prescient early investments in Facebook and Twitter. However, Milner is less interested than his counterparts in building a new space business than in supporting ventures to answer one of the most fundamental questions humans pose: are we alone?

Last year, Milner announced he was providing $100 million to a new initiative to support the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI), called Breakthrough Listen (see “A funding breakthrough for SETI”, The Space Review, August 17, 2016.) Now, he’s moving from listening for any signs of life in the universe to developing probes to go search for it directly.

At a press conference last Tuesday in New York—coinciding with the 55th anniversary of the historic flight of Yuri Gagarin, after whom Milner is named—he unveiled Breakthrough Starshot, an effort to develop tiny, laser-propelled probes that could cross the expanse between our solar system and the nearest star system, Alpha Centauri, in as little as 20 years.

Milner said he was motivated to pursue Starshot in order to pursue interstellar flight in a reasonable time frame. “How do we go faster? How do we go further? How do we make this next leap?” he asked.

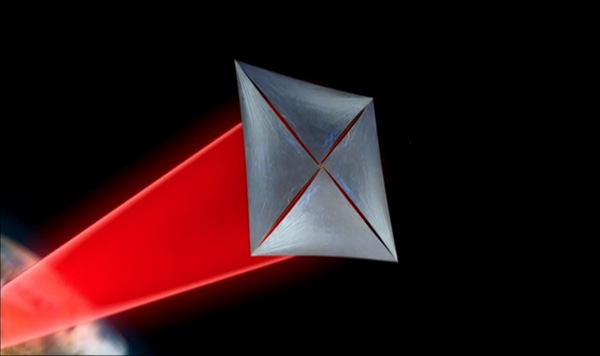

The answer, or at least the approach they’re pursuing, involves beamed laser propulsion, a concept that been examined over the years for applications ranging from low-cost launches of spacecraft into low Earth orbit to “laser sails” that propel spacecraft into interstellar space. Starshot is based on the latter, but with using very small spacecraft, weighing on the order of one gram.

The Starshot concept involves the development of a “nanocraft” comprised of two main elements. One is a “StarChip” that Milner described as being a chip with the area of a “large postage stamp” while being only slightly thicker than one, but outfitted with all the key subsystems of a larger spacecraft, including a camera, photonic thrusters, communications, and power (likely in the form of a speck of americium, a radioactive element.) The other is the lightsail, several meters across but extremely thin and lightweight, that would be attached to the StarChip to provide propulsion.

This is possible, Milner argued, because of several technological advances. Moore’s Law has helped shrink electronics down to a scale so that all the major components of a spacecraft can fit onto a chip. Nanotechnology enables lightweight materials for a sail attached to the chipsat that would capture laser light to propel it. And improvements in photonics can enable laser systems of up to 100 gigawatts needed to propel the spacecraft at speeds approaching a fifth of the speed of light.

“The Breakthrough Starshot concept is based on technology either already available or likely to be available in the near future,” Milner said. “But as with any moonshot, there are major engineering challenges to solve.”

That $100 million Milner has pledged for Starshot will go towards resolving those technical challenges, including research and development work that would result in a “proof of concept” of high-speed beamed propulsion of chipsats. It would, he said, “lay the foundations for an eventual voyage to Alpha Centauri.”

| “One of the challenges you’ll see in our list is the policy issue,” Worden said of the giant laser required. “We anticipate there would be international agreements in control of this.” |

Such a voyage, though, would likely be many years in the future. Milner and other panelists at the event didn’t give specific timetables for that mission, but suggested it would be decades away. It would also cost far more than the $100 million Milner is contributing: he estimated its cost would compare with “the biggest international science collaborations,” like the CERN particle physics laboratory, where billions have been spent over the years on accelerators like the Large Hadron Collider.

When that additional money would be needed, and from whom, isn’t known yet. Pete Worden, the former director of NASA’s Ames Research Center who serves as executive director of Starshot, said at the press conference he met with NASA leadership last week to brief them on the project. “They’re very eager to support us,” he said, adding that Starshot is open to working with other national space agencies to be as inclusive as possible.

Worden also said that Starshot was based on technology development that had been funded by NASA previously, particularly through its NASA Innovative Advanced Concepts (NIAC) program. Milner said that Starshot’s work would similarly be placed in the public domain for all to access (presumably within the bounds of any export control concerns that arise when talking about powerful lasers and advanced spacecraft components.)

Starshot’s leadership recognizes that there are many challenges they will have to overcome if anything like this mission becomes reality. The project’s website lists about two dozen such challenges they have already identified, mostly dealing with technology issues: how to develop the StarChip and the lightsail, and how to use a laser system to propel them to another star.

There are other challenges as well. At the press conference, one reporter asked just how much science one of these StarChips could do, speeding past the Alpha Centauri system at 60,000 kilometers per second. Avi Loeb, a Harvard University physicist who also serves as chairman of the project’s advisory committee, said a distant flyby of a planet there—about as far from the planet as the Earth is from the Sun—would last about an hour.

“You can take images,” he said. “In principle, we can probe molecules as we go through a medium. We can also measure magnetic fields. We can equip this smart electronics with all kinds of probes, and the idea would be to collect data that cannot be acquired from the Earth.”

There also the policy issues regarding developing a giant laser. While the laser could have peaceful applications in addition to launching nanocraft—Worden suggested it could be used in planetary defense to help deflect threatening asteroids—such a giant laser could also be threatening to any spacecraft in orbit.

“One of the challenges you’ll see in our list is the policy issue,” Worden acknowledged. The solution, he said, would involve some kind of multinational accord regulating the laser’s use. “We anticipate there would be international agreements in control of this.”

| “There are many challenges in this project. It’s an ambitious project, but we don’t see any showstoppers or any deal-breakers based on fundamental physics principles,” Loeb said. |

The Starshot team noted that while sending a mission to Alpha Centauri was their long-term goal, there were steps along the way that would be less difficult and ambitious than interstellar flight. Loeb said that the same technology could initially be used for high-speed exploration within the solar system, sending a spacecraft to fly by Pluto in just a few days, rather than the nine and a half years it took New Horizons to get there. (What science such a mission could do flying by a world about 2,500 kilometers across at potentially tens of thousands of kilometers per second, though, wasn’t quite clear.)

Starshot, even its proponents admit, is highly speculative. Developing the technology may take far longer, and cost far more, than Milner and his team expect, but they expressed confidence that it could, eventually, be done.

“There are many challenges in this project. It’s an ambitious project, but we don’t see any showstoppers or any deal-breakers based on fundamental physics principles,” Loeb said. “So we think we can overcome these challenges with enough innovation and ingenuity.”

“I don’t know how long it’s going to take,” said Ann Druyan of Cosmos Studios, another member of the project’s advisory committee. “I tend to be ridiculously optimistic, but of course none of these prognostications take into consideration the events on Earth that can derail us, and also the creative developments, like in technology, that can speed us on our way.”

Milner is, in the end, another multimillionaire or billionaire making a bet on space. While others invest in suborbital spaceplanes or reusable launch vehicles or orbital habitats, he is thinking in much bigger, and riskier, terms. And, since it’s only his money, and not the taxpayers’, at stake for now, there’s no need for hand-wringing about whether it’s a waste of money. (That value proposition will need to be looked at again, though, should Starshot seek additional funding from NASA or other space agencies to continue its project.) Starshot may well fail in its long-term goals, but who knows what it might achieve along the way.