Review: Under Desert Skiesby Jeff Foust

|

| At the beginning of the Space Age, astronomers treated studies of the solar system with a high degree of disdain, considering it the “disfavored stepchild of astronomy,” Sevigny writes. |

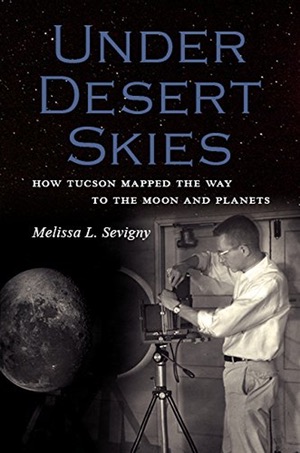

So how did the University of Arizona become such a key player in planetary science, a field that did not exist, at least in any recognizable form, a little more than a half-century ago? Under Desert Skies, by Melissa L. Sevigny, a science reporter for Arizona Public Radio, offers a concise history of LPL and Arizona’s planetary pursuits, told largely by the people who made it happen.

At the beginning of the Space Age, astronomers treated studies of the solar system with a high degree of disdain, considering it the “disfavored stepchild of astronomy,” Sevigny writes. The new generation of ever-larger telescopes developed in the mid-20th century was intended for stellar and galactic studies, and using them for studying the solar system was widely considered a waste. “No one wanted to study the Earth’s near neighbors: they were the stuff of science fiction, not science.”

An exception was Gerard Kuiper, the Dutch-born astronomer who was one of the few of that era interested in studying the solar system, including the Moon. At a meeting of the International Astronomical Union in 1955, he circulated a memo seeking astronomers interested in joining him on a project to create an atlas of the Moon. Only one person responded, British astronomers Ewen Whitaker, who would eventually join Kuiper’s project at Yerkes Observatory in Wisconsin.

| Kuiper was the driving force in the early years of Arizona’s planetary program, but he also comes off, among those who worked with or studied under him, as aloof and autocratic. |

But poor observing conditions at Yerkes, and discontented colleagues who thought the Moon was a waste of observing time, led Kuiper and his team to move. They alighted in Arizona primarily because of the good observing conditions promised there. It coincided with an effort by the university to raise its profile as a research institution. More importantly, it came as the Space Race heated up, raising the profile of, and funding for, the Moon and lunar research.

Kuiper was the driving force in the early years of Arizona’s planetary program, developing observatories but also getting involved in NASA missions, and even winning NASA funding for the building that would become the laboratory’s home. But Kuiper also comes off, among those who worked with or studied under him, as aloof and autocratic. “He had a talent for inspiring the public,” she writes, “but students who searched him out found him a difficult boss.”

Kuiper passed away in 1973, but the lab continued to grow and evolve, like the emerging discipline of planetary science—one that increasingly incorporated the geological sciences in addition to astronomy. That meant, over time, more people working on a wider range of research across the solar system. LPL also established its own culture and traditions, like the annual “Bratfest” party created by graduate students.

Under Desert Skies is an enjoyable history of LPL and the people who helped create not just an institute, but also shaped the development of a new scientific field. It’s based heavily on interviews Sevigny did with current and former faculty and staff. (The book, she notes in the prologue, was started at the request of then-director Michael Drake, who wanted to capture the history of LPL “from the old timers while they’re still alive”; sadly Drake passed away before that history was completed.) It’s a fascinating look at the people who created a laboratory and an institution.