Mining issues in space lawby Jeff Foust

|

| “Asteroid mining is cool. Everyone thinks it’s cool. But is it legal?” asked Dunstan. |

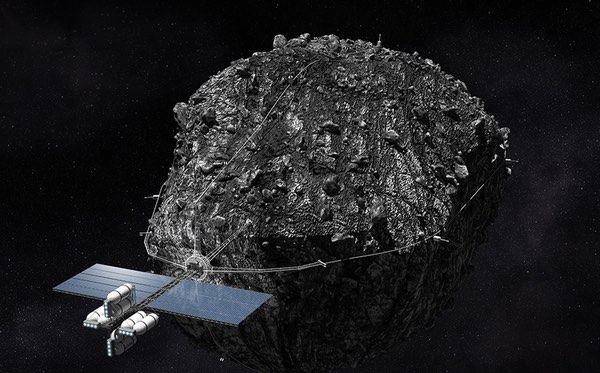

Planetary Resources, another space resources company, already launched its first tech demo satellite, Arkyd 3R, also a CubeSat, last year from the International Space Station. (The “R” designates it was a reflight of the original Arkyd 3, lost in the Antares launch failure in October 2014.) The company is planning to launch two more tech demo satellites later this year, company vice president Peter Marquez said during a panel last week, as part of a roadmap of missions leading up to the company’s first mission to an asteroid in 2020.

Those efforts are seemingly emboldened by the Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act (CSLCA), legislation passed by Congress and signed into law last November. A section of the law grants companies the rights to resources they extract from asteroids, which clears up, at least at the level of domestic law, the question of whether companies could own material they extract from an asteroid. Yet, even with that law in effect, there are still unresolved issues, both at the federal and the international level, for prospective asteroid miners.

Law versus treaty

The good news for the emerging space resources industry is that people are taking the subject more seriously than ever before. “The giggle factor is gone,” said Jim Dunstan, founder of the Mobius Legal Group, during last week’s panel on the issue in Washington organized by the Secure World Foundation. “Asteroid mining is cool. Everyone thinks it’s cool. But is it legal?”

While last year’s law, and a similar initiative in Luxembourg, have established the legality of asteroid mining in national law, there are still questions about whether it runs afoul of international law, primarily in the form of the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, the foundation of international space law. At issue is Article 2, which states that celestial bodies, including asteroids, are “not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means.”

The US has argued that the space resource language in the CSLCA complies with the treaty, since the government is not endorsing appropriation of the asteroid itself, but rather resources that have been extracted from it. That argument, though, is not universally accepted. Dunstan said he’s received an article to be published in an unnamed law review journal that argues that Article 2 overrides the CSLCA.

Dunstan notes that while objections to space resource rights law are often rooted in Article 2, they overlook Article 1, which permits the “exploration and use” of outer space, including celestial bodies, “without discrimination of any kind.”

There’s also the issue of customary international law, he said. Both the United States and the Soviet Union returned lunar samples, which they effectively claim ownership of. “NASA and the United States claims those 842 pounds [of lunar samples] to be a national resource. We’ve claimed ownership of the Apollo resources,” he said.

Other countries, though, have different views on the subject. The issue came up during a recent meeting of the legal subcommittee of the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) in Vienna. “What we’re going to seek to do now is to explain why we think these activities are consistent with the Outer Space Treaty,” said Kenneth Hodgkins, director of space and advanced space technology at the State Department, at the Secure World Foundation panel.

Hodgkins was at the COPUOS subcommittee meeting where some nations raised concerns about the new US law. “In particular, the Russians made several interventions, stating that what we did was inconsistent with our international obligations, that it was a unilateral act that undermines the international legal regime,” he said. “Generally, the view was expressed that this was a move to circumvent Article 2 of the Outer Space Treaty.”

| “There seemed to be a perception in the international community relative to the CSLCA that this was a unilateralist action, a land grab,” said Gold. |

Hodgkins said some other delegations were supportive of the US view, as well as outside organizations, like the International Institute of Space Law. Eventually, COPUOS members agreed to an agenda item for next year’s meeting for a “general exchange of views” on the topic. “At this stage, there will be no negotiation on any kind of a legal regime dealing with space resources,” he said. “It’ll be more, for our purposes anyway, of an educational exercise.”

Those who backed the CSLCA expressed frustration that the bill would become an international issue at all. “There seemed to be a perception in the international community relative to the CSLCA that this was a unilateralist action, a land grab, and that the US was disregarding its responsibilities under the Outer Space Treaty,” said Mike Gold, chairman of the FAA’s Commercial Space Transportation Advisory Committee (COMSTAC), during an April 27 meeting of COMSTAC’s international space policy working group in Washington.

“What frustrated me when I heard that is we put so much time and effort in ensuring that that piece of legislation not only was in conformity with the treaty, but that, after it was passed, we were in better conformity with the treaty than we were before,” he said. The response from some members of COPUOS, he said, “seemed to run counter to reality.”

Marquez, on the Secure World Foundation panel, said he was not surprised that some members criticized the CSLCA’s space resources provisions, simply because of the often-contentious nature of international relations in fora like COPUOS. “I’m sure Ken [Hodgkins] could come in with a PowerPoint slide that says, ‘Puppies are cute,’ and there would be a series of papers and objections to that.”

Authorize and supervise

At the national level, there’s an additional complication with another portion of the Outer Space Treaty. Article 6 of the treaty requires countries to perform “authorization and continuing supervision” of activities in space by non-government entities under their jurisdiction.

That is usually done in the United States by licensing of commercial activities: by the FAA for launches and reentries, by the FCC for communications, and by NOAA for remote sensing. But other emerging commercial activities, including not just asteroid mining but also lunar landers, satellite servicing, and commercial space stations, fall into gaps where there is no clear licensing authority and, thus, no means for the US to carry out its Article 6 obligations.

That is an issue that US companies planning so-called “non-traditional” space activities have raised in recent years, worried that, without the ability of the government to carry out its Article 6 obligations, it would not approve launch and other licenses needed for those missions. The CSLCA directed the White House’s Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) to study the issue, which the office said earlier this year was underway (see “Filling in the details”, The Space Review, February 8, 2016).

| “The goal needs to be providing the maximum certainty with the minimum regulatory burden,” Ingraham said. |

OSTP completed that study last month and submitted a report to Congress. That report endorsed a concept known as “Mission Authorization” that would closely follow the payload review done by the FAA as part of the launch licensing process, ensuring companies that planned non-traditional space activities complied with treaty obligations as well as national security and foreign policy interests of the US. The FAA would then maintain a registry of such authorizations, requiring companies to update them periodically. That, OSTP believes, would keep the US in compliance with Article 6 while minimizing any regulatory burden.

That model aligns with what some in Congress are thinking. The American Space Renaissance Act, unveiled by Rep. Jim Bridenstine (R-OK) last month, includes a section on that issue (see “An overview of the American Space Renaissance Act (part 3)”, The Space Review, this issue). While that comprehensive bill won’t pass intact, provisions like that could be inserted into other legislation that likely will pass by the end of the year.

The language in that section of the bill continues to be refined, said Christopher Ingraham, senior legislative advisor to Rep. Bridenstine, at the Secure World event. “The goal needs to be providing the maximum certainty with the minimum regulatory burden,” he said.

“I think we’re really close to an agreement among industry, and so we’ve already started having discussions with the State Department, with FAA, with DOD and OSTP about this language,” he said. “Our goal is to find a legislative vehicle for this language and get this done before this Congress ends.”

In the meantime, companies have tried to find ways to get government approval for non-traditional missions. Moon Express, a company developing lunar landers and competing for the Google Lunar X PRIZE, said last month it filed for an FAA payload review with additional voluntary disclosures that are intended to provide information to demonstrate to the government it will comply with treaty obligations. The outcome of that review has not been announced.

Even if successful, though, Marquez argued that there needed to be something like the mission authorization approach codified into law to ensure a consistent approach. “The ad hoc process is not the right way to go about doing things,” he said. “We need to have a process in place that is known, responsive, transparent.”

That, he added, has international benefits. “Industry can have stability, but also we can go to the international community and hold up a paper and say, ‘This is how we’re meeting our treaty obligations. What are you doing?’”

Even if Congress passes a law that includes a mission authorization scheme, and the international community accepts—grudgingly, perhaps, by some nations—the space resources language in the CSLCA, there will still be future challenges for asteroid miners. Dunstan pondered potential claims issues if a company announced plans to obtain resources from an asteroid, only to be beaten there by another company. Also, he asked, if a company mined a small asteroid and effectively extracted all of its mass, had it appropriated the asteroid in contravention of Article 2?

There are, Dunstan said, no easy answers to those questions, which for now remain hypothetical. “These are the tough scenarios that we’ve really got to work through as we talk about policy,” he said. But should those issues become less hypothetical in the coming years as companies like Deep Space Industries and Planetary Resources follow through on their asteroid mining plans, it will, at the very least, keep government officials and space lawyers busy.