The one space policy question for the candidatesby Jeff Foust

|

| “Honestly I think NASA is wonderful! America has always led the world in space exploration,” Trump wrote last week. |

Industry professionals and space advocates will certainly hope that the candidates offer more details about what they’ll do in the realm of space policy if elected. In their dreams, no doubt, they’d love to see Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump issue detailed white papers outlining what they’d do in civil, commercial, and national security space.

Well, good luck. So far the campaigns have said little about space. Last week, in a Reddit question-and-answer session, Trump declared, “Honestly I think NASA is wonderful! America has always led the world in space exploration.” That’s a departure from what former astronaut Eileen Collins said in her Republican National Convention speech a week earlier, when she said, “We need leadership that will make America’s space program first again.” Of course, Trump hasn’t gotten to this point in this campaign on the strength of his campaign’s ideological consistency.

At least Trump is talking about space, though. The Clinton campaign has been silent about space, and the draft version of the Democratic Party platform said nothing about space. NASA did make it into the final version, but it offered only glittering generalities and a vow to “strengthen support for NASA” in unstated ways. (The Republican platform, to be fair, also said little about space, recycling general language from its 2012 platform and supporting public-private partnerships, a tool used by both Republican and Democratic administrations.)

So those dreams of detailed space policy white papers will probably remain the stuff of space nerd fantasies. And little wonder: you can win a lot more votes on issues like terrorism or wage gaps than you can on whether or how to send humans to Mars. Even in swing states with a relatively strong space presence, like Florida, space is maybe a second-tier issue, at best.

And, to be honest, there isn’t a lot to talk about in civil space. It’s unlikely NASA’s science programs will be radically different in either administration: those efforts are guided by NASA’s implementation of various decadal surveys that represent the consensus of the scientific community. An administration can try to adjust the pace of those missions with funding changes (which Congress may or may not go along with, as the debate over planetary science funding in recent years demonstrates), but is highly unlikely to throw them out and start over. Aeronautics and space technology, meanwhile, are too small to merit much attention even in the best of times.

| If ARM is killed, what replaces it: cislunar habitats? A human lunar landing, perhaps in cooperation with Europe in its “Moon Village” model? Or a sprint to Mars? |

There is, though, an issue they can address that offers more leverage for the campaigns: human spaceflight. The exploration and space operations accounts, combined, represent the biggest slice of NASA’s budget (about $9 billion for fiscal year 2016), and virtually everything in them directly or indirectly deals with human spaceflight, from the ISS to SLS and Orion. And, despite all of NASA’s talk about being on a “Journey to Mars”, there’s still a lot of uncertainty about how to get there—or even if we should go.

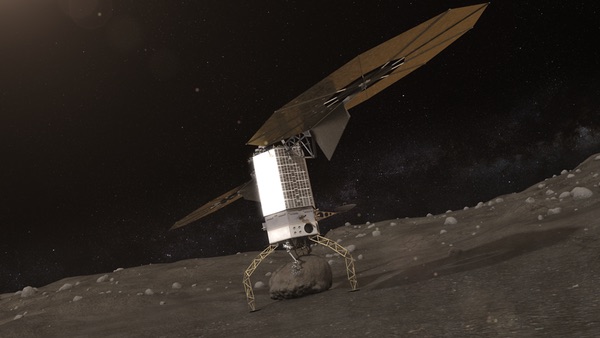

The next administration will be poised to make some major decisions about human spaceflight over the next four or eight years. One near-term issue will be the Asteroid Redirect Mission (ARM), which many think will be cast aside in the next administration. If so, what replaces it: cislunar habitats? A human lunar landing, perhaps in cooperation with Europe in its “Moon Village” model? Or a sprint to Mars?

The next administration will likely decide the fate of the ISS as well. The partners are just now wrapping up agreements to continue operations to 2024, which likely means by the end of Clinton of Trump’s first term in 2020, there will be talks about whether to extend it again, perhaps to 2028, or end it in 2024. If it’s extended, how long will it operate, and what will it do? If not, how will the station be wound down, and will commercial ventures like Bigelow Aerospace be ready to step up with their own stations by then? And, do plans for a Chinese space station affect that decision-making calculus?

There’s also the question about key programs like SLS and Orion. Recent reports by the GAO have raised doubts about the ability of those programs, especially Orion, to stay on schedule and budget. NASA is working to an August 2021 first crewed launch of Orion, which the GAO report states NASA has only a 40 percent chance of meeting. It also has a 30 percent chance of slipping that launch past April 2023. Would a Trump or Clinton administration be willing to continue supporting such a program, and—more importantly—could they get Congress to go along with major revisions or cancellations of them?

That’s a lot of policy questions to ask of campaigns that seem to get stuck on topics like whether or not a professional sports league sent them a letter about debate schedules. Odds are, they haven’t thought through most, if any, of those issues. (There’s also many military space issues that are arguably more important for consideration, but good luck getting campaigns to tell the difference between a JICSpOC and a JSpOC.)

So let’s boil down all those complicated human spaceflight policy questions into a simple one: why have a human spaceflight program today? Too often, we treat human spaceflight as a given—we have to have such a program—without thinking too deeply about why we spend roughly $9 billion a year on it.

There are many potential answers to such a question: national prestige and soft power (make America great again, or make it greater, or something like that.) Science, as astronauts unlock the secrets of the solar system and whether Mars supported, or supports today, life. Inspiring the next generation of explorers (and scientists, engineers, and maybe a policy wonk or two.) Making humanity a multi-planet species, unless NASA has entirely conceded that to Elon Musk.

| But to figure out what they want to do in human spaceflight, we should at least ask them why they want to do it. Is that too much to ask of the campaigns? |

(Or, perhaps, the answer would be not to spend the money at all: in the mid-2000s, the Republican Study Committee, a group of conservative members of the House of Representatives, proposed cutting funding for President George W. Bush’s Vision for Space Exploration as part of a broader set of spending cuts. The chairman of the committee at the time? Then-Rep. Mike Pence of Indiana, now Trump’s running mate.)

Figuring out that question should, ideally, drive what NASA’s human spaceflight programs do. Maybe that includes greater efforts to ensure there’s a commercial space station in place by 2024 to allow the ISS program to end, perhaps through the same kinds of public-private partnerships used in commercial cargo and crew, and also praised in the Republican platform.

Maybe it’s more international partnerships in human lunar exploration: NASA provides the heavy-lift rockets and habitat modules, and ESA provides the landers. That could open the doors for more partnerships with countries that are not interested, or feel incapable of contributing to, asteroid or Mars missions, and thus more soft power for the USA.

Or it might just mean staying the course: SLS and Orion, ARM and Mars, and so on. But to figure out what they want to do in human spaceflight, we should at least ask them why they want to do it. Is that too much to ask of the campaigns? Perhaps, but in this unusual election year you never know.