For planetary scientists, Venus is hot againby Jeff Foust

|

| Of the five finalists in the ongoing Discovery competition, two are Venus missions. |

Then there was Venus. Both American and Soviet spacecraft ventured to Venus starting in the early 1960s, thinking the planet might well be “Earth’s twin,” albeit slight smaller and apparently cloudy. Some still hoped those clouds might shroud a steamy, possibly habitable planet. Those hopes were quashed by the first successful Venus flyby mission, NASA’s Mariner 2 in late 1962, which measured very high temperatures at the planet that confirmed the prediction of a greenhouse effect made by an up-and-coming planetary astronomer named Carl Sagan.

More missions followed, confirming how much unlike Earth Venus was: a dense atmosphere riddled with sulfuric acid, and a surface that lacked the plate tectonics seen on Earth. By the 1980s, those missions petered out, after the Soviets managed to place several spacecraft on the surface that operated briefly before succumbing to the brutal conditions there. The same was true of missions to the Moon and Mars, but unlike those other worlds that have seen revivals of interest more recently, there’s been little activity on Venus.

NASA’s last dedicated Venus mission was Magellan, a radar mapper that launched in 1989 and ended five years later by burning up in the planet’s atmosphere. Only two other missions have flown to Venus since: Europe’s Venus Express, which operated in orbit from 2006 to 2014; and Japan’s Akatsuki, which finally entered orbit around Venus a year ago after a thruster problem prevented it from going into orbit in 2010.

Scientists who study Venus, though, are hopeful that more will be on the way. The next major milestone for Venus exploration will be an announcement expected later this month. That’s when NASA will announce the winner—or winners—of the ongoing competition for the next Discovery-class low-cost planetary science mission.

Of the five finalists for that selection, two are Venus missions. One, the Venus Emissivity, Radio Science, InSAR, Topography, and Spectroscopy mission, or VERITAS, is an orbiter designed to study the planet with a synthetic aperture radar (SAR), infrared sensors, and a radio science experiment to measure the planet’s gravity field.

“VERITAS addresses one of the most fundamental questions in planetary evolution: How Earth-like is Venus?” the mission’s lead officials state in a conference abstract about the mission earlier this year. “These two twin planets diverged down different evolutionary paths, yet Venus may hold lessons for past and future Earth.”

The other Discovery finalist mission destined for Venus is the Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble gases, Chemistry, and Imaging, or DAVINCI. This is an atmospheric probe, studying the various layers of Venus’ dense atmosphere during a 63-minute descent to the surface.

Like VERITAS, the DAVINCI team hopes to use the mission to understand why Venus is so different from Earth. “Understanding when and why the evolutionary pathways of Venus and Earth diverged is key to understanding how terrestrial planets form and how their atmospheres and surfaces evolve,” the mission team noted in a separate abstract at the same conference.

| “There’s an excellent chance we’ll be able to complete the [Discovery] selection and make that announcement before the end of December,” Green said. |

DAVINCI and VERITAS are competing against two missions to asteroids, Lucy and Psyche, and a near Earth object space telescope, NEOCam. (If nothing else, DAVINCI and VERITAS should win awards for the most convoluted mission acronyms.) NASA has indicated that it will select one, and possibly two, proposals for development by the end of December.

“We indeed are on track,” Jim Green, director of NASA’s planetary science division, said at a November 29 meeting of the Venus Exploration Analysis Group (VEXAG) in Washington, discussing the Discovery selection process. “There’s an excellent chance we’ll be able to complete the selection and make that announcement before the end of December.”

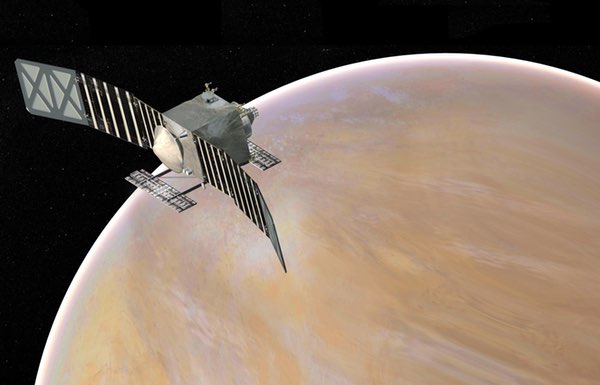

DAVINCI, another Discovery mission finalist, would probe the atmosphere of Venus during an hour-long descent. (credit: NASA/GSFC) |

Another opportunity for Venus missions just formally started last week. On Friday, NASA issued the final version of the announcement of opportunity (AO) for the next New Frontiers medium-class planetary science mission. That AO, effectively a call for proposals for such missions, had long been anticipated by scientists, but actually came out ahead of schedule: as recently as the VEXAG meeting, agency officials said they were planning to issue the AO by late January, only hinting it might come out sooner.

The AO restricts missions to one of six pre-defined categories. One of them is a Venus mission. “The Venus In Situ Explorer mission theme is focused on examining the physics and chemistry of Venus’s atmosphere and crust by characterizing variables that cannot be measured from orbit, including the detailed composition of the lower atmosphere, and the elemental and mineralogical composition of surface materials,” the AO states.

Such a mission would have a range of science priorities, listed without prioritization in the AO. They include studies of the physics and chemistry of the planet’s atmosphere, the various chemical and dynamical processes in the atmosphere, and properties of the planet’s crust, including any evidence of “past hydrological cycles, oceans, and life.”

Proposals are due to NASA by April 28. At the VEXAG meeting, Curt Niebur, the New Frontiers program scientist, said the current schedule calls for the selection of several proposals for “Phase A” studies by November. Those studies, which NASA will fund to the tune of $4 million each, will be due to NASA by October 2018. A final selection of one—and only one—mission is planned for May 2019, for launch by the end of 2025.

While the Discovery and New Frontiers program offer opportunities for NASA’s first dedicated Venus mission in more than a quarter-century, scientists at the VEXAG meeting were keeping other options open. One approach, called Venus Gravity Assist Science Opportunity (VeGASO), looks to take advantage of other spacecraft flying past Venus as gravity assists to other destinations. They include ESA’s BepiColombo mission to Mercury and two Sun missions: NASA’s Solar Probe Plus and ESA’s Solar Orbiter.

VeGASO requires Venus scientists to cooperate with missions that had no plans to study Venus en route to their destinations, seeing the planet as only a convenient trajectory-altering waypoint. Green noted that the two Sun missions originally had planned to keep their instruments off during the flybys. “There’s been a little look at what does it cost to turn the instruments on during the flybys,” he said, as well as whether the teams for those missions have the expertise to analyze Venus data. “That will be the next set of discussions.”

Scientists are also keeping their eye on an ambitious Russian mission, called Venera-D. The spacecraft would include an orbiter and perhaps a lander or atmospheric probe of some kind. Discussions have already been underway between Russian and American scientists on a potential US role on the mission.

| “I always reflect on the fact that we’re kind of the Galaxy Quest of scientists: Never give up, never surrender,” Stofan said. |

That effort has been complicated by strained relations between the US and Russia that hindered civil space cooperation outside of the International Space Station, but Green said he was able to win approval from the administration for a bilateral meeting with Russian counterparts in October. The result of that meeting, he said, was an agreement to extend discussions between scientists for two more years, focused on specific concepts for cooperation. “We’ll see if we can’t end up with a mission that can move into formulation as we move into the next decade,” he said.

Venera-D would be one of the most ambitious Venus missions ever, requiring a launch on a large Angara-A5 rocket in the mid-2020s. There is some skepticism, though, about Russia’s ability to carry out that mission, given its strained budgets and plans for a series of lunar missions, including sample return, planned through the 2020s.

Scientists at the VEXAG meeting were clearly trying to play up the prospects for Venus exploration, be it with a Discovery or New Frontiers mission or through other avenues. Bob Grimm, a Southwest Research Institute geophysicist who chairs VEXAG, talked at the beginning of the meeting about setting up a new website and a social media campaign popularizing Venus exploration, using the hashtag #UnveilVenus. “We’re trying to ‘social-mediaize’ this to get more discussion going on about Venus,” he said.

A social media campaign seems unlikely to sway source selection boards for NASA missions, but one theme that appeared to resonate among scientists was the idea of comparative planetology: studying Venus to better understand Earth. “It always comes back to Venus. There’s always something where Venus just slots in, saying we need to know this to figure out this puzzle of how planets work,” said Ellen Stofan, NASA chief scientist who, earlier in her career, worked on the Magellan mission.

Even the interest in recent years on so-called “Ocean Worlds” like Jupiter’s moon Europe and Saturn’s moon Enceladus could be tied into Venus, one scientist argued. “Although Ocean Worlds, in its programmatic sense, does not include Venus, there is a real sense in which Venus is, intellectually, an ocean world,” said David Grinspoon. He noted some recent research suggests Venus have had oceans of liquid water longer in its early history that previously thought. “It’s worth mentioning Venus in this excitement about Ocean Worlds, because there’s potentially a really important piece of that puzzle that fits into that theme.”

For now, though, Venus mission advocates wait for the announcement of Discovery missions, and the long process for selecting a New Frontiers mission. “I always reflect on the fact that we’re kind of the Galaxy Quest of scientists: Never give up, never surrender,” Stofan said. “We’re hanging in there, because we’re always drawn back to Venus, because it is so significant in terms of trying to understand the evolution of climates, planetary volcanism, habitable worlds.”