More Trek, less Warsby Dwayne Day

|

| I’ll admit that for me personally, Star Trek’s greatest appeal was its connections to spaceflight. That seemed like the future that I wanted to live in and the Enterprise was the starship that I wanted to live on. |

But although I loved Star Wars, I have always and forever shall be a Trekkie. Star Trek for me was far more inspirational and far more real than Star Wars ever was. Star Trek was a vision of what I wanted our future in space to be like, exploring strange new worlds and seeking out new life and new civilizations. Star Wars was about the battles, about black and white struggle, and it was mostly fantasy. Star Trek attempted to depict, or at least nodded toward, a more realistic and scientific portrayal of space exploration. Even if a lot of Star Trek’s technology violated the laws of physics, it at least implied that there were physics. The Enterprise entered orbit; it did not hover over a planet and turn on a dime. The distances between star systems were vast, and the Enterprise crew was very much alone in the final frontier.

Star Trek had connections to NASA even then. The first space shuttle was named Enterprise after Trekkies lobbied for it—although President Ford most likely chose the name because as a former naval aviator, he was familiar with the famous World War II aircraft carrier Enterprise. Star Trek’s Lieutenant Uhura, Nichelle Nichols, even served as a spokesperson for NASA, recruiting some of the first African American astronauts. Many people who grew up watching the show in the late 1960s, and then in endless reruns in the following decade, were inspired to go into space careers, some of them eventually working at NASA and JPL. Star Trek and NASA reinforced each other, whereas few people found lifelong inspiration in Star Wars. NASA was always far more Star Trek than Star Wars. NASA was about exploring new worlds.

I’ll admit that for me personally, Star Trek’s greatest appeal was its connections to spaceflight. That seemed like the future that I wanted to live in and the Enterprise was the starship that I wanted to live on. As a kid, my giant cutaway poster of the Enterprise was the source of endless daydreams, perhaps best summed up by a coffee mug I recently saw that says “I may look like I’m listening to you, but in my head I’m piloting the Enterprise.” I need that mug now, even when I’m running real honest-to-goodness space policy meetings.

Star Trek had strong characters, and it had philosophy. The 1979 film Star Trek The Motion Picture was frequently criticized for being dull, but it aspired to something big. The film included a profound scene where Spock takes Kirk’s hand and tells him that a simple feeling—their friendship—was beyond the alien machine V’Ger’s comprehension. And the end of the movie is about transcendence, both human and machine elevation to a higher state of being, and Spock’s realization that logic alone is insufficient for understanding the universe. The movie captured both the people and the philosophy that gave the show its depth. But there was also something deeper to Star Trek that was then, and still is, rare for science fiction. At its core, the show was about hope—not the simplistic hope of defeating evil like in Star Wars, but hope for our humanity.

Creator Gene Roddenberry had been a police officer and later a bomber pilot during the Second World War, where he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. He had seen humanity’s ugliness firsthand by the time he decided to work in Hollywood. By the 1960s, his philosophy reflected a mix of Kennedy-era New Frontier liberal optimism and a belief that our troubles were not going to overpower us. It was certainly utopian, and perhaps a bit naïve. The most basic theme of Star Trek was a belief that the future would be better than the past. Even during some of the darkest days of the Cold War and civil strife in America, Roddenberry believed that we would get through it: we would not simply survive, but thrive and travel outward to the stars.

| Star Trek was never trying to predict the future. It was trying to depict a future worth living in. |

Over a decade ago, Nicholas Evan Sarantakes, writing in the Journal of Cold War Studies, argued that Star Trek’s creators were not simply providing utopian entertainment. (See: “Boldly going: Star Trek and spaceflight”, The Space Review, November 28, 2005) The show’s critique of American culture and domestic policies had long been recognized by fans and critics, but Sarantakes wrote that Roddenberry and the other producers and writers also “wanted the United States to play a constructive role on the world scene” and that “they used the television show to critique U.S. foreign policy.”

|

In a recent essay, Peter Frase noted the difference between science fiction and futurism and argued that the latter—an attempt to directly predict the future—obscured the future’s inherent uncertainty and contingency and was ultimately stultifying. Frase suggested that science fiction was richer, more honest, and more humble. Star Trek, Frase wrote, “wants to root its characters in a richly and logically structured social world.”

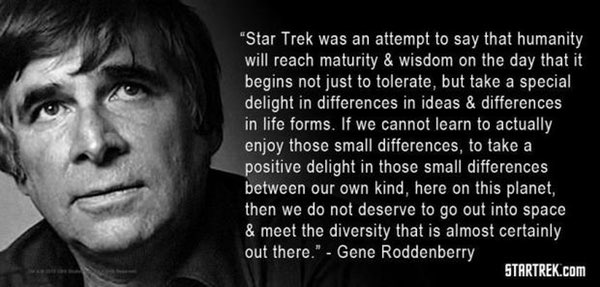

But Gene Roddenberry certainly had a philosophy, a humanitarian message, and Star Trek was his pulpit. Star Trek was never trying to predict the future. It was trying to depict a future worth living in. As Roddenberry said in 1976:

Star Trek was an attempt to say that humanity will reach maturity and wisdom on the day that it begins not just to tolerate, but take a special delight in differences in ideas and differences in life forms. […] If we cannot learn to actually enjoy those small differences, to take a positive delight in those small differences between our own kind, here on this planet, then we do not deserve to go out into space and meet the diversity that is almost certainly out there.

In that talk Roddenberry concluded:

The much-maligned common man and common woman has an enormous hunger for brotherhood. They are ready for the twenty-third century now, and they are light years ahead of their petty governments and their visionless leaders.

| What America needs is more of Star Trek’s vision, hope, and wonder and exploration and strength through diversity. |

It is no revelation to say that we appear to be heading for troubling times. We are moving from an era of a president whose foreign policy is a shambles into one where a president-elect casually tweets about building more of the most destructive weapons on the planet. The prospective leader of our democracy has talked about persecuting people based upon their religion, torturing prisoners, and killing the families of terrorists. We are transitioning from feckless to reckless, and xenophobia is in ascendance. It is hard to be optimistic about our future.

As entertainment, I enjoyed the recent Star Wars movie, and felt that it added surprising depth to a story that was previously primarily black and white. I have also been seriously disappointed at the three new Star Trek movies that have replaced Star Trek’s optimism and philosophy and vision with battles and fistfights and explosions. Perhaps the new Star Trek series that CBS will stream online will try to revive what made the original television series unique. What America needs is more of Star Trek’s vision, hope, and wonder and exploration and strength through diversity. Whereas the original Star Trek was so bold as to populate its bridge with a black woman, an Asian, a Russian and an alien, all working together, we need a new Star Trek that could put people of multiple races and religions and philosophies and orientations together and not only show them working as a team, but being stronger through their diversity, not simply in spite of it.

We need Star Trek. But even more, we need what it represents.