Tumult, continuity, and uncertaintyby Jeff Foust

|

| “I understand there’s a lot of apprehension, and in this point in time, a lot of questions still remain to be answered,” said Ban. “Give this country and give us all a chance. I bet it will turn out okay.” |

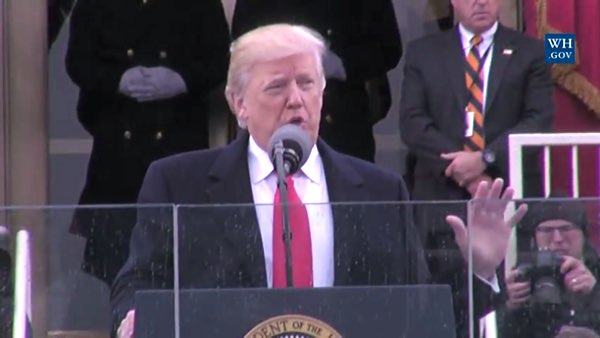

However, there hasn’t a transition quite like this in recent American history. The first week of the Trump Administration has seen a number of executive actions, most notably a ban on entry into the country by people from seven nations, but also widespread protests around the nation of both those actions and the administration in general.

Science has been affected by this as well. There were reports early last week that the Environmental Protection Agency had frozen its grant program, and also restricted communications with the media and public. Another report said that the Department of Agriculture had similarly prevented scientists there from talking with the media.

While this was happening, several thousand atmospheric scientists were gathering in Seattle for the annual meeting of the American Meteorological Society (AMS). As the conference started, there seemed little overt concern about what the new administration might do to weather and climate work at NASA and NOAA. A session on priorities for the new administration, held on the conference’s first full day Monday, focused primarily on issues like a weather forecasting bill making its way though Congress, and concerns about the effect a federal hiring freeze, announced by the White House earlier than day, would have on NOAA.

“I understand there’s a lot of apprehension, and in this point in time, a lot of questions still remain to be answered,” said one of the panelists, Raymond J. Ban, a consultant and retired Weather Channel executive. He stressed he remained optimistic. “Give this country and give us all a chance. I bet it will turn out okay.”

By the next day, as reports of the restrictions at EPA and other agencies leaked out—not to mention a National Park Service Twitter account “going rogue” that day by tweeting out climate facts in apparent defiance of restrictions placed by the new administration—the mood at a NASA town hall meeting at the conference was more unsettled. Michael Freilich, the director of NASA’s Earth science division, noted that the talk he planned to give was similar to those he offered recently, including at the American Geophysical Union’s Fall Meeting last month.

The difference, though, was that this was the first such presentation since the Trump Administration took office. Attendees wondered if NASA was facing the same restrictions on research and outreach that other agencies had reported. “Nobody has told us to change anything we are doing,” he said early on in his talk to a standing-room-only crowd.

Still, scientists at the meeting peppered Freilich with questions about potential restrictions, explicitly asking him if NASA had the same “gag order” that the EPA had. Freilich reiterated that was not the case. “NASA Earth science division, and I believe I can say the NASA Science Mission Directorate, have not been given any direction to change either what we are doing, how we are doing it or how we are talking about it, as of right now,” he said.

“Keep doing your work, keep making advances, keep building credibility,” he told the audience during his talk.

| “NASA Earth science division, and I believe I can say the NASA Science Mission Directorate, have not been given any direction to change either what we are doing, how we are doing it or how we are talking about it, as of right now,” Freilich said. |

As the week wore on, some of those restrictions at other agencies eased. The Agriculture Department rescinded its earlier ban on communications with the public, and the EPA lifted the freeze on most of its grant programs. Throughout this time, there was no evidence of any restrictions on NASA communications, even on areas like climate science that might prove to be politically sensitive.

Over the weekend, as the American Physical Society (APS) held its “April Meeting” in Washington, DC (the meeting is usually held in April, but moved to January this year because of scheduling issues), physicists also felt uncertainty in general about the state of science, in particular funding support, in the new administration.

“When I was asked to give this talk, it was in a different era,” said Cherry Murray, a professor of physics and of technology and public policy at Harvard University, and director of the Office of Science at the Department of Energy in the final year of the Obama Administration. She was part of a panel on science policy at the conference Saturday. “I don’t know, actually, what’s happening as well as any of you do.”

In her talk, she said she was concerned that research and development funding would be squeezed in the coming years because of fiscal pressures created by high budget deficits and the growing national debt. “We have a ballooning national debt. This is not sustainable.”

Rush Holt, a former congressman and current CEO of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, had his own concerns about the political climate on the panel. “This has been a truly puzzling year, or year and a half, politically,” he said. “I have never seen the scientific community so uncertain, so concerned, and truly anxious.”

Holt said he was concerned about a perceived erosion in appreciation of science by the public, which, at its root, he believes can be traced to how science is communicated to the public and to policymakers.

“We should shift from trying to communicate the right answer to communicating the right process,” he said. Simply giving an answer and asserting it’s correct, he argued, can be offputting and even counterproductive in an era when alternative sources—perhaps peddling, to use a now-infamous term, “alternative facts”—are readily at hand.

The panelists didn’t have any firm predictions to what would happen to funding and policies for federal science agencies in the new administration, nor did another speaker in a talk at the conference Sunday. “There’s no question we have undergone something that, quite frankly, I haven’t seen in my life,” said Michael Lubell, professor of physics at the City College of New York and former head of the American Physical Society’s Washington office.

| “This has been a truly puzzling year, or year and a half, politically,” Holt said. “I have never seen the scientific community so uncertain, so concerned, and truly anxious.” |

(Lubell and the APS severed ties in December, a month after he authored a press release that called for the incoming administration to support science funding because it would “help the Trump administration achieve its goal captured in its slogan ‘Make America Great Again.’” He wouldn’t comment on his departure from the APS other than to say, “I neither resigned nor am I retired.”)

Lubell believed that Trump won the election thanks to populist movements that are opposed to globalization of the economy. That could be an issue for scientists, he said. “We, as physicists, are comfortable working with colleagues from other countries, at facilities in other countries,” he said. “That is not how the people who voted for Donald Trump think.”

He argued that, for science to prosper in the new administration, it has to be argued in competitive, not collaborative, terms. “I believe we have to cast it in the form of competitiveness: ‘We have to win,’” he said. “I’m not saying I believe this, I’m just reflecting on how you want somebody to react.”

One wonders, then, how such lessons might be applied to NASA and its programs. Its current flagship human spaceflight program, the International Space Station, is very much that kind of collaborative effort that Lubell believes is no longer in favor. What might that mean for any potential extension of the ISS beyond 2024, or for similar collaborative efforts for human space exploration beyond Earth orbit?

But going it alone, or at least with a program much more strongly led and funded by the US, may also pose issues given the likely squeeze on R&D funding, and other non-defense discretionary programs, in an effort to reduce deficits. Would space programs get special treatment, or suffer the same cuts in spending that other R&D programs might face, particularly if science isn’t seen as a priority?

For now, it’s business at usual at NASA. Freilich, in his talk at the AMS meeting, noted there were no changes to his programs, which are funded at fiscal year 2016 levels though a continuing resolution that lasts until April 28. He thought that, in his personal opinion, the resolution would likely be extended through the rest of the fiscal year so that Congress could focus on the administration’s fiscal year 2018 budget proposal expected this spring.

There are, though, he added, no guarantees that will happen. “I don’t know any of the details,” he said of his agency’s budget plans. “I’m not sure that anybody knows any of the details of where we are going to go during this time.”