Taking salvage in outer space from fiction to factby Michael Listner

|

| However, the popular idea of “salvage” in outer space springs from a misconstruction of what salvage is in the maritime context and unfamiliarity with international space law. |

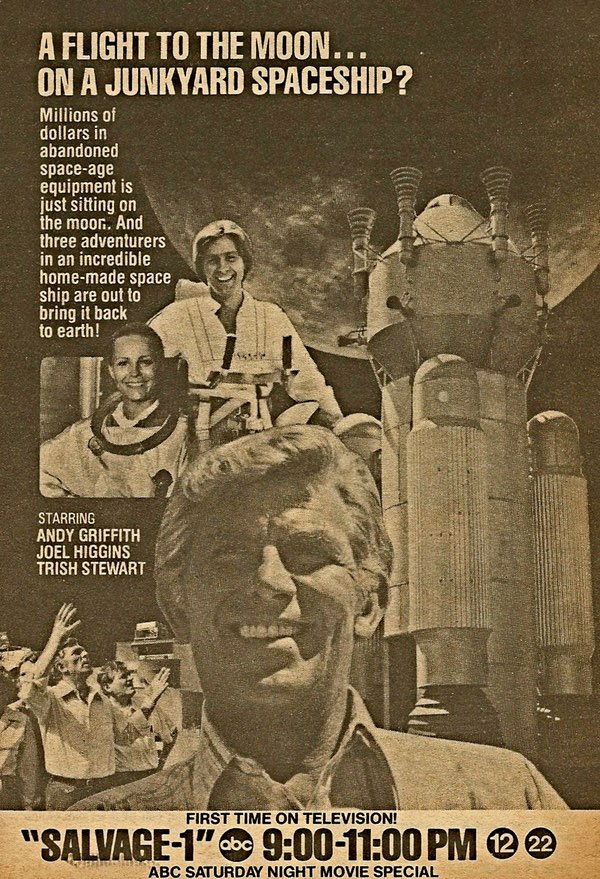

Salvage 1 was a stretch of the imagination, but it was fun and inspired excitement over spaceflight during a time when the United States was in a lull between Apollo/Skylab and the launch of the first Space Shuttle. Salvage 1 took a step beyond the theme of human spaceflight and made some interesting forecasts to the era commercial space we live in now. For instance, Harry finds himself pestered by an FBI agent, Jack Klinger, who acted as a foil to stop Harry from going to the Moon. Obviously, he failed, instead becoming a sometimes ally and sometimes hindrance to Harry’s space activities. Salvage 1 also introduced legal concepts through the FAA registering his reusable rocket, the Vulture, acquiring licenses to operate the spacecraft, and even a reference to Harry’s activities as commercial space.

Salvage 1’s plot revolves around the idea of salvaging space objects, including space debris, from outer space, including the Moon. At the time Salvage 1 was created, the field of space law was obscure: the Outer Space Treaty just 12 years old and had only of a fraction of the parties it has today.3 Still, the concept of salvage in outer space is a popular one that reverberates as a future commercial space activity, which is echoed by futurists and space advocates alike. Like Salvage 1, the concept of “salvage,” latched onto by the advocacy community, compares the maritime concept of “salvage” to a future outer space activity. However, the popular idea of “salvage” in outer space springs from a misconstruction of what salvage is in the maritime context and unfamiliarity with international space law.

“Salvage” versus “the law of finds” in the maritime context

The purpose of salvage in the context of maritime law is to encourage persons to render prompt, voluntary, and effective service to ships at peril or in distress by assuring them compensation and reward for their salvage efforts. Rather than obtaining title to the salvaged property, a salvor acts on behalf of the property’s owner, thereby obtaining a security interest or lien against the property saved.4 In other words, salvage does not warrant possession of the property to the salvor. Rather it entitles the salvor to compensation for return of the property to its owner.

The term “salvage” is often misconstrued with the law of finds, which allows a finder of abandoned property to acquire title by reducing the property to personal possession.5 This misapplication of the law of finds is mistakenly applied to the concept of “salvage” in premise of Salvage 1 and also by space enthusiasts and advocates alike.

Contract salvage and pure salvage

There are two types of salvage recognized by maritime law. One is contract salvage, where a salvage service is entered into between the salvor and the owners of the imperiled property, or by their respective representatives. This is pursuant to an agreement, written or oral, fixing the amount of compensation to be paid whether successful or unsuccessful in the enterprise.6 This entails the law of contracts with bargained for legal detriment, i.e. consideration.

| Certainly, the adventurers in Salvage 1 were seeking to apply the law of finds as opposed to salvage, but because of Article VIII of the Outer Space Treaty, they were in fact acting more along the lines of pirates by appropriating property belonging to the United States and demanding a ransom. |

In contrast, there is pure salvage, which is a voluntary service rendered to imperiled property on navigable waters where compensation is dependent upon success, without prior agreement or arrangement having been made regarding the salvor’s compensation.”7 Pure salvage does not involve bargained-for legal detriment and the compensation due falls under the theory of quantum meruit.8

Federal warships and the conundrum of Article VIII

A twist in the law of finds and pure salvage is found with federal warships.9 Federal warships in distress or wrecked are not considered salvageable nor subject to the law of finds, unless they are expressly abandoned.10 This principle of international law is not a product of treaty but rather is a precept of customary international law, which has been supported by maritime and admiralty courts worldwide.11

Article VIII of the Outer Space Treaty takes a similar tack to this customary norm with objects launched in to space, as it creates an express tenet that grants a state continuous possession over a space object registered under its jurisdiction:

A State Party to the Treaty on whose registry an object launched into outer space is carried shall retain jurisdiction and control over such object, and over any personnel thereof, while in outer space or on a celestial body. Ownership of objects launched into outer space, including objects landed or constructed on a celestial body, and of their component parts, is not affected by their presence in outer space or on a celestial body or by their return to the Earth. Such objects or component parts found beyond the limits of the State Party to the Treaty on whose registry they are carried shall be returned to that State Party, which shall, upon request, furnish identifying data prior to their return. [emphasis added]

In other words, once a space object is launched into outer space, it continues to be registered to the country that launched it even it returns to Earth, much in the same way a federal warship continues to belong to its nation of origin. This concept applies to space objects owned by non-governmental organizations and governmental organizations alike.12 The effect of this continued ownership and jurisdiction is similar to federal warships in that the maritime concept of the law of finds and pure salvage are not applicable.13

At first blush, this would appear to create a barrier to commercial entities to engage in future activities to resembling salvage in outer space, in particular for activities involving the removal of space debris. Certainly, the adventurers in Salvage 1 were seeking to apply the law of finds as opposed to salvage, but because of Article VIII of the Outer Space Treaty, they were in fact acting more along the lines of pirates by appropriating property belonging to the United States and demanding a ransom. Yet, all is not lost for salvage in outer space because, while an outer space analog of pure salvage and the law of finds would be precluded, there does exist the potential for a form of salvage based on contract salvage.

A contract salvage analog for private/commercial space

As discussed earlier, contract salvage involves a contract, whether written or oral, between the salvor and the owner of the imperiled property. Because contract salvage does not reduce the imperiled property to the salvor’s possession (unless the agreement stipulates the salvor’s compensation is the property itself or a portion thereof) there would be no issues with the need for abandonment.14 In fact, there is precedence for contract salvage being performed on space objects launched under the jurisdiction of the United States.

| The sky is the limit as to how contract salvage can be utilized by private/commercial entities, but underlying those activities classified as contract salvage is the question of the level of government supervision and regulation required. |

In February 1984, shuttle mission STS-41B launched the commercial satellite Palapa B2 for the Indonesian government, but it failed to reach geosynchronous orbit due to a malfunction of its perigee motor stage. While it was circling the Earth in a useless orbit, the satellite was purchased by Sattel Technologies of California from the insurance group that covered the loss. Sattel subsequently contracted with NASA to retrieve the satellite, which it did in 1984 along with the similarly stranded Westar VI.15 Sattel subsequently contracted with Hughes Aircraft Company, which originally manufactured the satellite, and the launch service provider, McDonnell Douglas, to refurbish and re-launch the satellite. The satellite was renamed Palapa B2-R and was successfully re-launched in April 1990. After the re-launch title of the satellite was transferred back to Indonesia16.

Notably, the salvage of Palapa B2 (and Westar VI) was done by an agency of the United States government and not a private/commercial entity. However, this precedent does not preclude private/commercial entities from performing missions that could be classified as contract salvage.17 Indeed, Orbital ATK’s planned satellite servicing with its Mission Extension Vehicle (MEV) could be considered a form of contract salvage, and its licensing, including payload review, could form a template for the FAA to approve contract salvage activities by private/commercial entities. Other forms of contract salvage for outer space could include space debris removal from low Earth orbit or removal of derelict satellites in he GEO. As spacecraft such as United Launch Alliance’s planned Advanced Cryogenic Evolved Stage (ACES) upper stage comes online, private space activities will be facilitated to expand the concept of contract salvage to remove derelict satellites and repurpose them for cislunar infrastructure where the satellites themselves are the compensation.

The sky is the limit as to how contract salvage can be utilized by private/commercial entities, but underlying those activities classified as contract salvage is the question of the level of government supervision and regulation required. Surely, any space activities that involve contract salvage will implicate national security, which means Article VI of the Outer Space Treaty will be at the forefront. Hence, it is for the lawyers and political bodies to accept the realities of international legal obligations with regards to private/commercial space activities and focus on developing a regulatory and licensing regime in a manner that doesn’t discourage future activities, but instead addresses the realities those activities will entail.18

Conclusion

Like Harry Broderick, those of us in the space community have a dream, and that dream is to see private/commercial space open up outer space for development. Salvage 1 served to entertain and fill a gap for a generation that just witnessed humankind landing on the Moon and awaiting next phase of space activities. Yet, the premise of a television show holds seeds of reality within the fiction it espouses, and separating the chaff of fiction and applying the legal realities of international law to those seeds can mature them into the fruit of private/commercial space activities.

However, the pull of fiction is strong in the sense that we willfully disregard actualities because the fiction is more appealing. This holds true for the concept of salvage in outer space and puts us at a juncture: do we hold onto the fiction espoused by entertainment, or do we face the realities and create a legal concept that harmonizes with international legal obligations? Therein lies the challenge, like most other aspects of private/commercial space, in that we must be willing to separate fiction and deal with the reality to reach the dream we have.

Endnotes

- Opening narration to Salvage 1 starring Andy Griffith.

- The opening clip for Salvage 1 one can be found on YouTube.

- Arguably, the field of space law is still obscure, but it is much more prominent than it was in 1979.

- See R.M.S. Titanic, Inc. v. The Wrecked & Abandoned Vessel, 742 F.Supp.2d 784, 793 (E.D.Va. 2010).

- See Odyssey Marine Exploration, Inc. v. Unidentified, Wrecked and Abandoned Sailing Vessel, 727 F.Supp.2d 1341, 1344 (M.D.Fla. 2010) at Footnote 1, citing 3A Martin J. Norris, Benedict on Admiralty § 159 (2002).

- See New Bedford Marine Rescue, Inc. v. Cape Jeweler’s Inc., 240 F.Supp.2d 101 (D. Mass. 2003) at Footnote 1, citing 3A Martin J. Norris, Benedict on Admiralty § 159 (2002).

- See Id.

- Quantum meruit is Latin for “as much as he deserved,” the actual value of services performed. Quantum meruit determines the amount to be paid for services when no contract exists or when there is doubt as to the amount due for the work performed but done under circumstances when payment could be expected. This may include a physician’s emergency aid, legal work when there was no contract, or evaluating the amount due when outside forces cause a job to be terminated unexpectedly. If a person sues for payment for services in such circumstances the judge or jury will calculate the amount due based on time and usual rate of pay or the customary charge, based on quantum meruit by implying a contract existed. See Law.com.

- A warship is defined in international law as a ship belonging to the armed forces of a nation bearing the external markings distinguishing the character and nationality of such ships, under the command of an officer duly commissioned by the government of that nation and whose name appears in the appropriate service list of officers, and manned by a crew which is under regular armed forces discipline. See Annotated Supplement to the Commander's Handbook on the Law of Naval Operations (15 Nov 1997), Chapter 2, Sec. 2.1, p. 2–2. See also High Seas Convention, art. 8(2); 1982 LOS Convention, art. 29.

- See Sea Hunt v. Unidentified Shipwrecked Vessel, 221 F.3d 634, 643 (2000).

- “Traditionally, maritime law has found abandonment when title to a vessel has been affirmatively renounced, or when circumstances give rise to an inference that the vessel has been abandoned; courts have found abandonment, for instance, when a vessel is so long lost that time can be presumed to have eroded any realistic claim of original title." Northeast Research, LLC v. One Shipwrecked Vessel, her Tackle, Equipment, Appurtenances, Cargo, 790 F.Supp.2d 56, 64 (2011). In determining whether circumstantial evidence, supports an inference of abandonment by clear and convincing evidence, courts consider factors such as lapse of time, the owner's nonuse, the place of the shipwreck, and the actions and conduct of the parties having ownership rights in the vessel. Id. at 65.

- The continuing jurisdiction of Article VIII also extends to objects launched by non-governmental entities and the non-governmental entities as well. Thus, if a private object or personnel launched into outer space is interfered with by an object or personnel with from another nation, the nation who has continuing jurisdiction would be looked to provide protections per Article VIII whether legal or otherwise. Article VIII can also be read in conjunction with the legal obligations in Article VI.

- Theoretically, abandonment of space objects could take a similar tack as the maritime concept of abandonment. There is no legal support in the court or the corpus of international space law to support this approach, but it is a possible method that could be developed through customary practice, non-binding international norms or even a bottom-up approach through domestic law that could be adopted as custom.

- There are examples of contract salvage in the maritime context being performed on federal warships. A recent example is the Oscar II-class submarine K-141 Kursk, which sank with all hands on August 10, 2000. The Russian government did not expressly abandon the Kursk, but it did contract with the Dutch companies Mammoet and Smit International and, in essence, gave Dutch nationals permission to salvage the submarine and return it to its owner (the Russian government) for a fee.

- The Westar VI communication satellite was launched on the same space shuttle mission and likewise failed to reach GEO. The planned salvage mission similarly involved Westar VI. There was much work to be done by Hughes prior to the space shuttle mission to recover the satellites to make them retrievable. A good account of the salvage mission can be found on a Hughes history website.

- Palapa B2 was registered originally as 1984-011D and listed as “recovered” in the UN Registry of Space Objects and listed as registered to Indonesia. After launch Palapa B2 was re-designated Palapa B2R and registered as 1990-34A and registered to the United States. Apparently, after Palapa B2 was purchased by Sattel, registration transferred to the United States. This made salvage less legally complicated as Palapa was under US jurisdiction when it was salvaged and not Indonesia thus eliminating the need to go through diplomatic channels to obtain permission from the Indonesian government to perform the salvage operation.

- The Reagan Administration issued [a still classified] revision of National Security Decision Directive Number 42 (July 4, 1982 National Space Policy) that among other provisions revised the policy for the commercial sector in that “the United States government shall not preclude or deter the continuing development of a separate, non-governmental Commercial Space Sector. Expanding private sector investment in space by the market-driven Commercial Sector generates economic benefits for the Nation and supports governmental Space Sectors with an increasing range of space goods and services. Governmental Space Sectors shall purchase commercially available space goods and services to the fullest extent feasible and shall not conduct activities with potential commercial applications that preclude or deter Commercial Sector space activities except for national security or public safety reasons. Commercial Sector space activities shall be supervised or regulated only to the extent required by law, national security, international obligations, and public safety.” This directive prevented the government from performing further commercial launches with the Space Shuttle and has the effect of preventing the government from performing future contract salvage operations for non-governmental entities. See NASA Fact Sheet, “Presidential Directive on National Space Policy,” February 11, 1988, Commercial Sector Guidelines.

- The author is considering a form of “mission authorization” for private space activities that would not involve an interagency review such as the “mission authorization” scheme proposed by the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy under the Obama Administration. The author has done a preliminary proposal and presented it to a member of the House of Representatives.