Buzz Aldrin will not stop talkingby Dwayne Day

|

| They know that he is the space equivalent of Grandpa Simpson: once he starts talking, he won’t stop, and he doesn’t care if nobody is listening, or if he’s interrupting the conversation, or if he is inconveniencing others. |

Several years ago, Buzz showed up at a workshop of the Lunar Exploration Analysis Group, which was happening at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory where he was getting a tour. He took over the microphone and had his Mars slides put up on the screen and started into his Mars pitch. About twenty minutes into his stream-of-consciousness address, he paused and asked what group he was speaking to. When informed that they were lunar scientists he said, “I don’t care about the Moon, I’m here to talk about Mars,” thereby insulting everybody in the room, including those studying the lunar samples that he brought back to Earth in 1969.

By now, anybody who has been in the space field or attended a few space conferences knows this about Buzz. They know that he is the space equivalent of Grandpa Simpson: once he starts talking, he won’t stop, and he doesn’t care if nobody is listening, or if he’s interrupting the conversation, or if he is inconveniencing others. He is oblivious to most social norms. More than oblivious, he is obnoxious. He informed one panel of aerospace engineers that his Mars plans were better than theirs, adding, “All I have is intuition, which is a lot more than you.” If he was just about anybody else, he would be yanked off the stage.

At H2M several times during panel discussions he seized the microphone and started into various sales pitches—either his Mars plans, his foundation, or his book or TV projects. He did the exact same thing last year, so conference organizers knew what they were in for. They could have turned off his microphone, but apparently concluded that it would be rude to silence the rude astronaut. (See “A year on Mars”, The Space Review, May 31, 2016.)

Buzz may have been the second person to walk on the Moon, but he was probably the first to remove the shine off the All American Boys myth of the early astronauts. His 1973 book Return to Earth—later made into a TV movie—included his admission about suffering from depression and alcoholism and shared the kinds of personal details that most people would consider embarrassing, or at least would never tell in polite company.

One of the things that comes through loud and clear in Return to Earth is Buzz’s insecurity. He needs the attention, but it will never be enough and it fuels most of his actions. It used to be that American culture frowned upon admissions of alcoholism and depression, so Aldrin’s airing them in the early 1970s was bold and with little precedent. Then American culture changed and praised these admissions, labeling them “brave.”

What do we owe our heroes? What do our heroes owe us?

In the early days of the space program NASA, aided by a questionable agreement with Life magazine, sought to portray the first astronauts as the embodiment of American values. Good husbands, fathers, family men, patriots, professionals. It would have been naïve even at that time to expect them all to be from the same cookie cutter mold. Perhaps that mold was legitimate in one dimension only: they were all competent, even outstanding, pilots.

| Neil Armstrong in some ways was the most perplexing for people because after doing all the parades and the talks and the interviews, he decided that he had had enough and wanted to get back to a more normal life, however one in his situation could define “normal.” |

But it is still surprising in retrospect to see just how totally different many of these men were in their other traits. Some of them embraced wacky UFO theories. Others went into business, sometimes with dubious results. Most of them seemed to be willing to use their space experience to continue to make money, although few seemed truly committed to space exploration. Pete Conrad was considered by many of his fellow astronauts to be an outstanding pilot and commander, swore like the sailor he was, but in his later years seemed dedicated to making reusable rockets, both as an engineer and entrepreneur. Dave Scott worked with lunar scientists and college students. Alan Bean painted his experiences.

Neil Armstrong in some ways was the most perplexing for people because after doing all the parades and the talks and the interviews, he decided that he had had enough and wanted to get back to a more normal life, however one in his situation could define “normal.” He became a professor and turned down interviews, and people started to refer to him, inaccurately, as a “recluse.” There were some space buffs who were bitter about Armstrong’s refusal to be who they demanded that he be, to embrace the things they wanted him to embrace, to push for more space exploration, to continue to make appearances and sign autographs and allow the public to own him.

I never bought the “recluse” label, and in fact, when I contacted him in 2010 about serving on a committee looking at NASA’s research aircraft program, Armstrong readily accepted. He was friendly, quiet, even a bit dull. But he was still willing to talk about Apollo, and one of the thrills of my life was when he made an impromptu presentation where he narrated his lunar landing to a small group of aeronautics experts. Armstrong knew who he was and he accepted it with quiet dignity. He had nothing to prove.

Buzz Aldrin has been the most prolific and outspoken space exploration advocate of all the early astronauts. He has been talking about space exploration ideas since at least the 1980s, but he has also been marketing himself and various products for decades. In early 2009, he lobbied successfully to be included in Obama’s inauguration day parade and was rewarded a year later when he got to fly with Obama to a speech at Kennedy Space Center where the president sought to prop up a flailing space exploration plan for NASA. Buzz’s talk to the president onboard Air Force One may have been the origin of Obama’s been there, done that comment about the Moon, from which NASA is still recovering. (See “Moonbuzz”, The Space Review, Monday, October 18, 2010.)

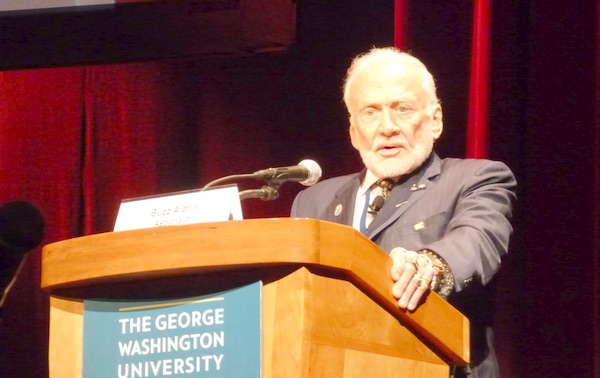

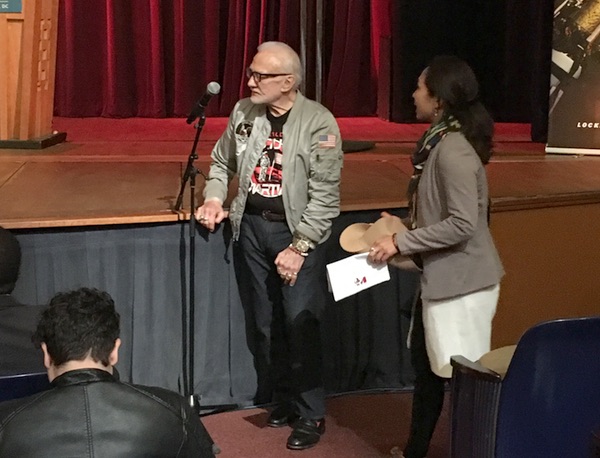

As the Humans to Mars Summit ended May 11, Aldrin stood at a microphone, seeking one final opportunity to talk. (credit: J. Foust) |

Our heroes are rarely who we want them to be…

It was not Buzz’s post-Apollo space advocacy that catapulted him to renewed stardom. In 1995, the movie Toy Story featured the character Buzz Lightyear, which launched Buzz into the vernacular. In 2002, he famously punched a Moon landing denier in the face. Later in 2009, after marching in Obama’s parade, Buzz got even more publicity when he hitched his star to rapper Snoop Dogg, whose shtick included marijuana use and who even had his own line of pornographic videos. Buzz rapped alongside Snoop, proving that there was no media gig that he would decline. That undoubtedly led to his appearance a year later on Dancing With the Stars. Even though he was eliminated early, the show exposed Buzz to a new generation that had never really known him, and soon he was making other TV appearances as himself, like on CBS’s top-rated The Big Bang Theory. As Buzz entered his 80s, he finally became a brand.

| Why do space conferences and events invite Buzz Aldrin to speak when they know this is going to happen? It is because he is a celebrity, a brand, and he draws some people to attend so they can shake his hand and take a selfie with him. |

Buzz’s talk at H2M was about Mars cycling spacecraft, an idea that he has been talking about since 1985 and which seems to have gained little traction even among space enthusiasts. He advocated the concept with increasing vigor in the 1990s but stopped for a few years to pitch a reusable spaceplane, later returning to the cycler and wearing a t-shirt with a line from the movie Total Recall: “Get your ass to Mars!” He presents his slides to audiences at every opportunity—even barging in uninvited—and his charts have gotten more and more complex over time. His latest version includes a programmatic flow chart. (Unfortunately, at the end it does not say, “Start the reactor, free Mars!”)

Why do space conferences and events invite Buzz Aldrin to speak when they know this is going to happen? It is because he is a celebrity, a brand, and he draws some people to attend so they can shake his hand and take a selfie with him. And it is almost certainly because the organizers of events remain enthralled, either by Buzz, or by his celebrity. The 1999 film Being John Malkovich managed to perfectly capture this phenomenon. In the film people are able, through a mysterious tunnel, to enter into actor John Malkovich’s body for a short time. One person does this while Malkovich is at home, ordering new bath towels over the telephone. The interloper emerges fifteen minutes later, dropped into a ditch near the New Jersey Turnpike, but still totally enthralled—he was John Malkovich! There will always be people who want to be Buzz Aldrin.

Buzz Aldrin is many things. He is impolite. He is opinionated. He is not lazy. He is brave. Not too long ago he became the oldest person to ever visit the South Pole—a trip that nearly killed him when he suffered from altitude sickness.

Viewed from one perspective, Buzz is a visionary, a salesman, a prophet. He certainly believes the Mars story he is advocating. But inevitably, the story is still all about Buzz. Multiple times at H2M after the various panel discussions when the moderator would allow questions from the audience Aldrin—who camped out next to a microphone—would be the first to grab the mic and then start talking, about whatever he wanted, even if it had little to do with the panel. At one point, after talking for over seven minutes, the moderator asked if Buzz had a question. “Question?” Buzz asked, puzzled. No, of course not. He had forgotten who was on the stage, or even why he had grabbed the microphone.

Douglas MacArthur once memorably said that soldiers never die, they just fade away. Buzz Aldrin will someday die, but he will never fade away.