Why should we go?Reevaluating the rationales for human spaceflight in the 21st centuryby Cody Knipfer

|

| In this present era of national challenges which demand the attention of policymakers and the public it is more important than ever for the space community to reflect on the purpose of human space exploration. What value does it hold? |

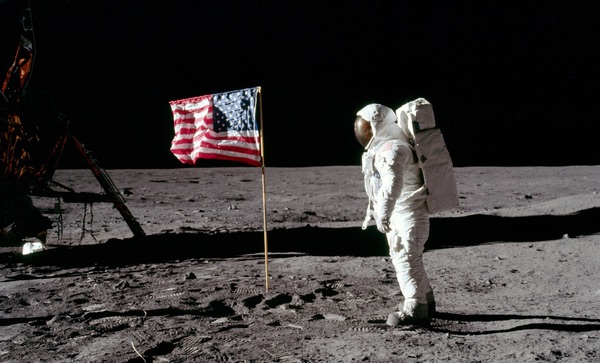

For many, if not most, who study, work on, or follow human spaceflight, the prevailing reason for its continuation intuitively exists beyond practical or material motivations: simply because space, to quote President Kennedy’s famous speech at Rice University in 1962, “is there.” To them (us), a meaningful rationale is not so much a justification of why human spaceflight could continue as it is a defense of why it should. Humanity’s expansion into space is taken as an ordained inevitability and our pursuit of it a compelled calling. It is understandable, then, the consternation felt when confronted with the hard reality that a majority views human spaceflight as a lesser priority than other projects, that humans have been essentially mired in low Earth orbit since the apex in exploration that was the lunar landings, and that most of the more audacious human spaceflight efforts have faced intense fiscal pressures, programmatic instability, or outright cancellation.

In this present era of national challenges which demand the attention of policymakers and the public—economic uncertainty, international turmoil and change, domestic political and social upheaval—it is more important than ever for the space community to reflect on the purpose of human space exploration. What value does it hold? Are the oft-repeated reasons that have sought to justify the enormous cost of human spaceflight applicable in the current day? Will advocates of a robust human presence in space be met with the same disappointments in the coming decades as they have in those that have passed?

This will all ultimately depend on how the question of human spaceflight’s efficacy as a tool for society is answered. Whether the justifications for human spaceflight are cohesive with national desires will be, as John Logsdon noted in Which Direction in Space, “key to decisions on the future of government space programs around the world.” If found, “the 21st century could see the full realization of both the practical and inspirational potentials of space.”1 If not, human spaceflight may remain a far muted shadow of the grandiose visions (and expectations) put forth by the likes of von Braun and O’Neill.

As the United States works to develop a coherent and cohesive national space strategy, a reconsideration of the rationales behind human spaceflight and their relevance in the policy arena is increasingly warranted. Reevaluation and discussion of these rationales can, hopefully, enable the space community to better align its intent and aspirations with the needs of the nation.

At the same time, the space “ecosystem” is rapidly and dramatically evolving. Private and commercial entrants with human spaceflight aspirations are becoming more extricated from the pressures and constraints of public policy and funding. Will rationales justifying their efforts even be necessary? Perhaps, for as long as they continue to interface with (and rely upon support from) government-run programs. But as spaceflight becomes more democratized with actors who can privately finance their efforts, the fundamental issue of “why” may simply turn into a question of markets and economics.

Space exploration and public policy

To begin a discussion on the rationales of spaceflight, it need be acknowledged that the space effort does not exist in a vacuum (at least metaphorically.) Rather, for most of its history, space exploration, particularly that involving human flight, has been a matter of public policy. Especially in the United States, funding and programmatic decisions have been the purview of leaders in the executive and legislative branches. While granted leeway in strategic and practical implementation of missions, NASA as an agency is subordinated in goal-setting and resource allocation to the ideas, decisions, and whims of its political leaders. The character of the human spaceflight program, its successes, stumbles, and failures, are a result.

| Those who advance the cause of publicly-funded human spaceflight find themselves operating in a larger political context and competing against equally worthy causes. |

In public policymaking, rationales matter—persuasive ones appealing to the whole of or influential actors within society especially so. This is significant in a country such as the United States, which has a political system sharply characterized by competing groups—political parties, advocacy groups, industry organizations, scientific societies, to name a few—with distinct and active interest in shaping the nation’s direction, its allocation of resources and energy. Their goals and aspirations are often starkly different, at times contradictory. Their motivations range from the ideological to the practical and material.

Moreover, they exist and operate in a resource-constrained environment. While the federal budget may grow and shrink, the United States’ government is limited to a finite amount of money it can throw toward its entire portfolio of projects and activities. Where the government chooses to allocate those funds is the product of policymaking: the process of judging and prioritizing the disparate needs and desires of stakeholders in the system.

The same holds true abroad, in countries with similarly representative political systems and those without. Even in authoritarian systems and command economies, limitless opportunities are bounded by limited resources. Where leaders decide to put their time and money are strategic decisions which cater to the interests of internal actors with political clout or which advance the standing—be it diplomatic, economic, or prestigious—of the state.

Those who advance the cause of publicly-funded human spaceflight find themselves operating in a larger political context and competing against equally worthy causes. To win support (and money), the rationale they put forth needs to be persuasive across a broad spectrum of political factions, appeal to potential supporters and opponents, and meet the perceived needs of large and diverse economic and political constituencies. In lack of a persuasive rationale, a proposed effort will be superseded by others seen by the broader polity as more realistically and immediately achievable or necessary.

This is a challenging task. That human spaceflight has, throughout its history, remained an ancillary part of public policy reflects the space community’s continuing struggle to arrive at a rationale compelling enough to heighten its stature on the policy agenda. Of course, this challenge is compounded further by the present-day practical circumstances of spaceflight: that “space is hard”: dangerous, costly, resource and time consuming, and technically difficult. Where there is overlap in purpose between human spaceflight and a cheaper terrestrial option, it is difficult to justify going with the former over the later.

Logsdon described this as the “potential liabilities associated with using space systems to carry out centrally important functions for society,”

“Such systems remain expensive to develop and launch. They have mixed records of reliability, and repair of problems or failures is at best very difficult… [w]hen these factors are taken into account, do space systems indeed compare favorably with terrestrial alternatives for carrying out the same function? Are there unique and valuable functions that only space systems can perform?”2

Logsdon’s last question is particularly key. Is there a function that only human spaceflight can perform, one which outweighs its costs? If there is, it has evidently not been properly articulated to policymakers or executed to its fullest potential in the past few decades. This notion is reflected in the Columbia Accident Investigation Board’s 2003 report, which made a condemning recognition of “the lack, over the past three decades, of any national mandate providing NASA a compelling mission requiring human presence in space.”3

Rationales for human spaceflight

Against this framing of the political environment’s dynamics, the most commonly advanced rationales for human spaceflight can be better addressed and understood. Academics, policymakers, industry leaders, and space enthusiasts have all weighed in with their justifications for why we—as a country, society, and species—should and will send humans into space. Many are deduced in retrospect, analyses informed by historical actions taken to meet past circumstances, challenges, and opportunities. Some are longer-term utopian prognoses, driven by ideological ideals, economic aspirations, and concepts of indefinite human survival. Others are more philosophical in nature, drawing on such notions as humanity’s inherently exploratory and adventurous character and “destiny.” Perspectives are diverse and occasionally disparate.

| Recognizing the pressures involved in public policymaking, the geopolitical rationale appears, at least historically, the most significant and compelling. |

The oft-repeated rationales for human spaceflight are also reflective of the interests held by the various stakeholders of the space effort. For scientists and researchers, for example, it is to advance scientific research and knowledge. For commercial space companies, especially those that have emerged in the recent decade, it is to advance the sphere of economic activity beyond Earth. For policymakers, it is frequently cited as a means to advance the interests of their constituency and the nation: spaceflight creates high-skill, high-wage jobs, inspires the next generation of workers to fill those jobs, and is a tool for international prestige, cooperation, and leadership.

Roger Launius’s seminal Compelling Rationales for Spaceflight laid out five major themes used to justify efforts in space: geopolitics/national pride and prestige, national security and military applications, economic competitiveness, scientific discovery, and human destiny/survival of the species. Returning to Logsdon’s question on the unique value of spaceflight, he noted that, of these, “only the human destiny/survival of the species and geopolitics agendas require humans to fly in space.”4 This largely holds true, at least in the present day. Much scientific discovery in space can be and is accomplished through robotic spacecraft. National security space systems are all automated. Indeed, early efforts for national security-related human spaceflight, such as the Manned Orbiting Laboratory program, were cancelled in favor of non-human spacecraft. Meanwhile, most of the present-day economic value derived from space is done through satellites orbiting the Earth.

Recognizing the pressures involved in public policymaking, the geopolitical rationale appears, at least historically, the most significant and compelling. Underlying this is the fact that international events and circumstances, acting as forcing functions, can either heighten or lessen human spaceflight’s stature as an element of public policy and policymakers’ willingness to allocate resources toward it. Human spaceflight has, at least historically, been most valued as a part of the foreign policy “toolbox,” as a method to deal with emerging external challenges. As Roger Handberg put in his Rationales of the Space Program,

“one needs an incentive, a compelling focusing event, strong enough to break through the existing political status quo and to place the issue of space on the policy agenda for political decision-making and policy formulation.”5

Closely related to the geopolitical rationale is that of prestige and national pride. Human spaceflight, as an enormously challenging yet rewarding task, reflects a country’s scientific, technological, and industrial strength. It is meant to appeal to audiences both domestic and international. The pride rational of human spaceflight, in the view of Harold Goodwin in Space: Frontier Unlimited,

“[S]hould be enough without all the other reasons and rationalizations that have been presented. It is the proper motivation of a prideful people with vitality, a sense of destiny, and confidence in their own ability.”6

The prestige and pride rationale is salient across the programs of the world’s space powers, and especially so the Chinese human spaceflight program. Goodwin’s assertion is reflected in the 2011 and 2016 white papers laying out China’s purpose for space exploration, China’s ambition for space achievement is driven by a belief that the prestige benefits that result increase China’s national power, thereby enhancing China’s overall influence and giving China more freedom of action in a region where it seeks heightened hegemony. Moreover, the human spaceflight program is intended to demonstrate the strength and validity of the Chinese leadership to domestic constituencies:

“[A]s a single-party undemocratic state built upon the Chinese Communist Party’s legacy, the leadership seeks to tangibly demonstrate progress that resonates with the Party’s narrative of continual economic prosperity, scientific achievement, and national pride and unity so as to legitimize continued one-party rule… spaceflight is conducted to demonstrate that the Chinese Communist Party is the best provider of material benefits to the Chinese people and the best organization to propel China to its rightful place in world affairs.”7

The prestige rationale can also be seen in nearly every human spaceflight effort the United States has undertaken. As noted by Launius,

“The United States went to Moon for prestige purposes, but it also built the Space Shuttle and embarked on the space station for prestige purposes as well… [p]restige will ensure that no matter how difficult the challenges and overbearing the obstacles, the United States will continue to fly humans in space indefinitely.”8

Prestige and pride are powerful motivators, but are they alone enough to justify a robust human spaceflight program? Apparently not in the minds of policymakers, who weigh it against other indicators of national prestige, such as a strong national defense, global humanitarian presence, or leadership in the arts, athletics, or terrestrial sciences. Rather, it seems that the prestige and pride rationales for human spaceflight are most compelling in two cases: first, when there is a development in space that threatens the prestige of the nation and the pride its citizens hold in it. The Soviets beating the United States in orbiting the first satellite and astronaut, for example. Second, when a country sees space prestige as a method to complement and buttress a broader and pressing geopolitical goal. Such is the case for China, which actively seeks hegemony in the Asia-Pacific and hopes that its space program will demonstrate superiority over neighbors. Notably, at present both a distinct threat in space that threatens national prestige and a specific strategic goal that’s actively supported by leadership in space are lacking for the United States.

| Yet despite President Kennedy’s rhetoric laying out these rationales, a singular reason existed for Apollo’s conception and drove its continued funding and execution. The United States had to beat the Soviet Union to the Moon. |

This relates to Handberg’s notion of “compelling focusing events,” to which we return. Demonstrative of their importance, it is around these events which most of the enthusiastic narratives of human spaceflight have been built. The Apollo project, the shuttle program, the International Space Station were all successes the have been the product of fortuitous alignment of rationales put forward by domestic interests, the existence of external challenges those rationales were cohesive with, and political will to expend the necessary funds to achieve them.

Let’s explore these in turn. The Apollo landings, as perhaps the seminal series of events in the history of human spaceflight, have been ascribed with a slew of reasons for why they occurred: to promote peace “for all mankind,” to advance the technological and industrial capacity of the nation, to conduct scientific research and discovery. Yet despite President Kennedy’s rhetoric laying out these rationales, a singular reason existed for Apollo’s conception and drove its continued funding and execution. The United States had to beat the Soviet Union to the Moon. Without the broader context of the Cold War, Sputnik and Gagarin, the failed Bay of Pigs invasion and the Cuban Missile Crisis, the effort of landing on the Moon would not have begun or, if it did, the government would not have dedicated over four percent of annual GDP to achieve it. And, of course, once the “race to the Moon” was solidly won, subsequent missions lost political appeal and were accordingly cancelled.

Rationales put forth for the International Space Station include scientific research and international cooperation. It need be remembered, though, that the project evolved out of Space Station Freedom: a Reagan-era proposal for a US station that faced stiff Congressional skepticism for reasons of funding and purpose. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Russian economic crisis, and concerns about a diaspora among the Russian space industrial base, the United States brought in Russia and other international partners to the station project. In effect, the ISS found political support where Space Station Freedom failed for the prestige the project could achieve in a new global order, for the cost-sharing of a partnered effort, and in that it could serve to coopt Russian talent lest they went abroad to build space systems—or ICBMs.

Now, with the space station’s operational costs consuming a significant portion of NASA’s budget and its R&D output being less than expected and preferred (especially in the much anticipated field of space-produced pharmaceuticals), it is understandable that the agency, policymakers, and partners are noncommittal to extending its lifetime beyond 2024 or flying a follow-on platform after it deorbits.

The space shuttle was intended for cheap and routine access to space but, just as important, as a vehicle to deliver critical national security payloads, conduct classified missions, and (perhaps) retrieve and return sensitive satellites from orbit. Much of the will to fund it came from the Defense Department’s interest in the vehicle, which manifested in a complex set of design requirements. When the shuttle failed to live up to the former purpose and was significantly scaled back for the latter following the Challenger disaster, the program was arguably left adrift in search of a mission, eventually transforming into what was essentially a construction and delivery service for the ISS. It is not surprising then, even if disconcerting, that the program was ended without a follow-on capability in place.

And for these successes, there are others where an alignment of rationale and need didn’t exist outright, where the rationales put forward fell short of addressing an immediate national challenge, where the resources required couldn’t be justified when put against alternate projects. The whole of the Space Transportation System, the Space Exploration Initiative, the Vision for Space Exploration, and (to some) the “Journey to Mars” come to mind.

| Many of the rationales used to justify a human spaceflight program are either ancillary to the politically compelling purpose of meeting a perceived national crisis and geopolitical challenge, or are applied after the fact. |

How so? The Space Transportation System, of which the Space Shuttle was envisioned as just an element of the larger architecture, found itself struggling for political buy-in and resources in the wake of the “victory” of the space race and competing with the rising pressures of the Vietnam War and domestic social change. The Nixon Administration could only justify a part of the program, the vehicle that had won Defense Department buy-in and had distinct national security purposes. Moreover, the decision to move ahead with the shuttle was as political as it was motivated by some space-related rationale: Nixon didn’t want to be seen as the President who “killed the space program.” The Space Exploration Initiative, with a total price-tag of over $500 billion, was balked at by Congress for its cost. The Vision for Space Exploration was cancelled because, as suggested by President Obama in so many words, the United States had “already been” to the Moon. And today’s “Journey to Mars,” with its significant schedule slippage, aborted asteroid redirect element, and currently unfunded cislunar “proving ground” phase, seems to be faring little better.

Lessons from past programs

Several general points can be derived from these successful and failed human spaceflight projects of past. Foremost is an affirmation of the importance of the “compelling focusing event,” as described by Handberg, in providing the political impetus and will for starting and continuing support for a program to fly humans in space. The Apollo program and the International Space Station may have fulfilled important purposes—fostering international cooperation, demonstrating the United States’ leadership, enabling scientific discovery—but their inceptions were catalyzed as distinct policy responses to meet specific circumstances. The political consensus for each program coalesced around the perceived national need to address the external challenges of the “space race” and of the Soviet Union’s collapse.

These spaceflight programs won the support of broad enough political constituencies to be executed not merely because they involved outer space, but because they were seen as better tools to accomplish a strategic goal than terrestrial alternatives. As such, the substantial public funding and continued programmatic stability necessary for their success was provided until such time as the national need was met—but not much further after that. Other failed proposals, such as the Space Exploration Initiative or Vision for Space Exploration, would have equally fulfilled scientific, exploratory, and prestige purposes, but lacked a forcing function significant enough to warrant the creation of strong political coalitions that could bring them to fruition.

This leads to a second important point: that many of the rationales used to justify a human spaceflight program are either ancillary to the politically compelling purpose of meeting a perceived national crisis and geopolitical challenge, or are applied after the fact. Science, exploration, inspiration, as described above, are all often-cited rationales that are almost inherent elements of any effort in space. Yet they have rarely, if ever, been the explicit and primary purpose of human spaceflight. As noted earlier, stakeholders of the spaceflight effort seek to justify that effort by the interests they hold: scientists desire discoveries and research, and justify programs for their scientific benefits; educators and politicians see spaceflight’s inspirational value as a method to bring students into science and technology, and therefore talk of the jobs created by it. But these alone are not enough to catalyze a new program. The groups who advance them do so in the hope that policymakers, of whom they’re constituents, will continue to support the space effort to advance their vested interest. As perhaps best said by Robert Colborn, “most of the motives advanced for [human spaceflight] seem… more like by-products than like major purposes.”9 This is not to minimize the value of these rationales, but to underscore their apparent unimportance in the creation of public policy pertaining to space.

Third, the rationales ascribed to a human spaceflight program generally lose importance or relevance once the program’s main purpose is complete and, accordingly, political will to sustain that program wanes. This is especially evident in the Apollo Program, where follow-on missions that carried scientific benefit were nonetheless cancelled after the United States clearly demonstrated its technical and scientific prowess. This again suggests the ancillary value of most rationales to the space effort and the significance instead of singular goals that a human spaceflight program seeks to achieve.

From these points, an overall conclusion can be drawn about human spaceflight, at least as a government-run effort. It is a tool to achieve immediate national needs toward which political consensus and will exists. More often than not, that consensus and will emerges from factors and circumstances in the broader domestic and international environment. Rationales justifying a program are equally valid and invalid depending on how they align with the necessity that program sets out to address, and may be reflected in political rhetoric regarding that program, but are generally not alone the driving force for its inception or even its sustainment.

Members of the space community should draw their own conclusions about their rationales from these points. Several suggestions, however, can be offered:

- While obviously having value, the conventional rationales for human spaceflight are evidently not compelling enough to win sustained support from broad political coalitions or raise the stature of human spaceflight in the policy agenda. Continuing to justify human spaceflight on the basis of these rationales is unlikely to result in dramatic shifts in the space program. The space community either needs to find new rationales to justify spaceflight, or redefine the scope and character of those they currently do.

- Rationales that are compelling must appeal to groups across the political spectrum, constituencies which exist outside the space community, and to policymakers who have immediate vested interests elsewhere. They cannot advocate for space for space’s sake alone; rather, they must advocate for space as a means to support society’s goals back on Earth. And to be successful against groups competing for the same limited resources, they must address current pressing needs (i.e. beat the Soviets to the Moon) rather than long-term or utopian ideals (i.e explore the unknown, settle outer space.) The space community’s rationales need to be more focused, short-term, and relevant to the needs of people on Earth.

- Rationales need an external forcing function, a “compelling focusing event,” to have relevance. The space community needs to be alert for perceived crises in the international and domestic arenas against which they can align their justification for spaceflight to drive the policy discussion. They must act as policy “entrepreneurs” by selling their rationales to policymakers as solutions to these problems.

Commercial human spaceflight rationales

Up to this point, this piece has discussed the relevance of rationales as they pertain to government-run efforts and public policy. But, again, the character of spaceflight is quickly changing with commercial and private actors entering the fold. Similar to the public sector, private companies are bounded in their desires by available resources. In the private sector, available resources are determined by market returns and capital investment. Where investors choose to allocate their funds is the result of risk calculation, market forecasting, and, occasionally, personal motivation. Likewise, where customers choose to spend their money is a decision on the perceived value of the service they will receive.

| By eliminating the pressure felt in the public sector to balance resources among competing groups, market-based human spaceflight enables other rationales to become more prominent so long as they are profitable. |

This warrants a brief look at the economic rationale for human spaceflight. Despite the growing optimism among the enthusiastic public and the private sector about the economic rationale for human spaceflight, it remains to be seen whether a sustainable and profitable economic endeavor in space requires a human presence. Tourism, be it on suborbital spacecraft, circumlunar flights, or orbital platforms, is approaching, but is unlikely to be a robust market or catalyze a dramatic growth in human presence in space. Unless the cost of spaceflight is dramatically reduced, tourism will remain the province of a niche community of the ultra-wealthy. And while space companies such as United Launch Alliance and Blue Origin talk about “a cis-lunar economy” and “millions of humans living and working in space,” there is still no clear answer as to what economic activity those humans would be doing. In-space assembly, manufacturing, and production can be automated, as can lunar and asteroid resource mining. If the ISS is to be trusted as a case study, basic and applied research conducted by humans is not a “killer application” for making money in space either.

Nonetheless, these companies will strive to see whether human spaceflight can be made economical. At present and into the near future, a variant of the economic rationale for human spaceflight could be seen as compelling, at least for the short-term: to see if a sustainable economic activity exists in space. Unlike the policy arena, whether this rationale remains compelling will not be judged against the needs of various constituencies and public interests, but by the market and the wallet.

This last point is important: by eliminating the pressure felt in the public sector to balance resources among competing groups, market-based human spaceflight enables other rationales to become more prominent so long as they are profitable. This is particularly true for the “utopian” rationale of human spaceflight: colonizing other worlds, ensuring humanity’s indefinite survival, and creating new civilizations in the space frontier. This utopian rationale has always been an underlying assumption of human spaceflight, even if it has not been applied as a distinct or even ancillary goal of programs to date. Taken against the analysis above, this is understandable: it does not address an immediate and distinct national need, there is no forcing function for it (nor, hopefully, will there be, considering that would entail some sort of extinction-level event occurring), and it is difficult to see how it would win support from powerful political groups who worry more about first improving the plight of Earth and those living upon it. Nonetheless, per Launius,

While “[t]he quest for utopia in space has been implicit rather than explicit, there has never been any question but that the long-term objective of spaceflight is human colonization of the cosmos. Virtually all models for the future of spaceflight have at their core human expansion beyond Earth.”10

This motivation underlies the plans of Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk, who indeed see the economic rationale of their companies’ plans as a means toward this end. While the latter rationale will necessarily rely upon the success of the former, it is easy to see an undeniable paradigm shift occurring with the embrace of the utopian rationale as a key purpose for human spaceflight.

The future of human spaceflight

Taken all together, what does this mean for human spaceflight in the coming decades? It is, of course, impossible to foresee the future, but some predictions may be made. Unless the United States faces a geopolitical crisis which warrants a space solution or develops a national grand strategy which cohesively integrates human spaceflight as a valued tool to achieve its aims, it is unlikely that the stature or funding of its human spaceflight program will increase. Large spaceflight programs with enormous costs will likely continue to face significant fiscal pressures and programmatic instability as space policy ascends and descends in political importance. Even if, as said by Launius, prestige and pride will ensure that the United States continues to fly humans in space, they will not guarantee a robust human presence or the success of an ambitious program; there is no reason to assume so, if they haven’t done so historically. Meanwhile, other “rising” countries with distinct geopolitical goals, such as China, will continue to exploit the prestige factor of human spaceflight until such time as their aspired position is obtained.

| The answer to “why” will change according to circumstances, politics, and economics. Still, attempting to find a definitive and singular answer for it will likely remain as popular an activity as it is an ultimately futile one. |

However, if the private sector succeeds in its economic aspirations, human spaceflight may become more prevalent and the rationales used to justify it more varied. There could emerge a successful synthesis of the private sector’s aspirations, justifications, and capabilities with the civil space program’s goals and needs: humans in space because of economic reasons working to support a government-directed program, for example. This synthesis of capabilities and rationales may be key to the 21st century’s “full realization of both the practical and inspirational potentials of space.”

Does all of this answer the question of “why?” No. Perhaps this is because it is a question without a single, compelling, definitive answer. The answer to “why” will change according to circumstances, politics, and economics. Ultimately, it comes down to spaceflight’s value as a tool to be used when the time and circumstances are right. And still, attempting to find a definitive and singular answer for it will likely remain as popular an activity as it is an ultimately futile one. What would be more fruitful for the space community is not continuing to seek them out; instead, it would be find a way to adjust the answers which do exist in such a way to make them compelling when the country needs to address a crisis and is asking “how.”

Endnotes

- John M. Logsdon, “Which Direction in Space?” Space Policy, May 2005. Pg. 88.

- Ibid. Pg. 87.

- Ibid.

- Roger D. Launius, “Compelling Rationales for Spaceflight: History and the Search for Relevance” in Steven Dick and Roger Launius, Eds. Critical Issues in the History of Spaceflight (2006). Pg. 68.

- Roger Handberg, “Rationales of the Space Program” in Eligar Sadeh, Space Politics and Policy, 2002. Pg. 29.

- Harold Leland Goodwin, “Space: Frontier Unlimited” (1962). Pg. 111.

- Cody Knipfer, “The Asian Space Race and China’s Solar System Exploration, Domestic and International Rationales,” The Space Review, 2016.

- Roger D. Launius, “Compelling Rationales for Spaceflight: History and the Search for Relevance” in Steven Dick and Roger Launius, Eds. Critical Issues in the History of Spaceflight (2006). Pg. 50, 52.

- Robert Colborn, “In Our Opinion,” International Science and Technology, January 1963. pg. 19.

- Roger D. Launius, “Compelling Rationales for Spaceflight: History and the Search for Relevance” in Steven Dick and Roger Launius, Eds. Critical Issues in the History of Spaceflight (2006). Pg. 43.