Making The Farthest journey: An interview with director Emer Reynoldsby Emily Carney

|

| “I always thought Voyager such a romantic, inspiring, and exciting story, and it’s really not an exaggeration to say that it is humankind’s greatest journey of exploration ever.” |

Yet the Voyager Grand Tour was almost rendered impossible, given problems both probes suffered right out of the gate, and during their missions. Voyager 2 suffered “vertigo” (as described by space historian Ben Evans) as it rolled and pitched during its August 20, 1977, launch aboard a Titan IIIE-Centaur, then had issues making its burn toward Jupiter. In 1981, its camera swivel stuck as it transited behind Saturn, rendering images blank while engineers back on Earth scrambled to come up with a fix. Meanwhile Voyager 1, launched two weeks after its sister spacecraft on September 5, 1977, also faced launch vehicle problems: its high-energy Centaur upper stage was forced to burn longer than expected, with only moments to spare before its mission was jeopardized.

These moments of adversities (and triumphs) are explored in a recently-released documentary about the Voyagers, The Farthest: Voyager in Space. Directed by Emer Reynolds, the film discusses the missions’ nascent beginnings when the program was saddled with the unwieldy sobriquet of Mariner Jupiter-Saturn 1977, the iconic flybys, and the famous “Pale Blue Dot” image taken by Voyager 1 as it looked back toward Earth—by then less than a pixel wide—in 1990. It also delves into the contents of the Voyager Golden Record. Flown aboard both spacecraft, this messenger may, one day, illuminate the images and sounds of our world to distant, as-yet-unknown civilizations.

I had the opportunity to conduct an interview with Reynolds, and asked her about the timeless lure of the Voyager program, the diverse community of people behind the spacecraft, and what inspired her most about the missions.

In the last 50-plus years of spaceflight, there have been many iconic space probes and landers launched, encompassing the Mariner, Pioneer, Viking, and Cassini programs, and far beyond—not to exclude the many Russian and European spacecraft that also have explored our solar system and universe. What made you choose the Voyager program as a subject?

Emer Reynolds: I always thought Voyager such a romantic, inspiring, and exciting story, and it’s really not an exaggeration to say that it is humankind’s greatest journey of exploration ever. That one little spacecraft, on ’70s technology, with 240,000 times less memory than that of an average smartphone, could visit all four planets of the outer Solar System, and reveal its wondrous beauty and diversity for the first time...Voyager [still had] enough wild drama in her to keep going and reach interstellar space, becoming the first human-made object to do so! I think, as the great Larry Soderblom, geologist on the Voyager mission, says in the film, “There will never be another mission like it! It was the first and last of its own kind.”

| “At one film festival a scientist approached me in tears, to say how validated she felt by the film’s inclusion of so many women.” |

Plus this wondrous tale of the spacecraft and its curious and precious cargo, the Golden Record, was one that amazingly had never been told on a cinema screen before. There had been fine TV documentaries made, but it had never been given the full epic cinema treatment that this glorious and thrilling story deserves. It has the classic elements of all great stories: compelling, emotional characters; adventure, ambition, and danger; dazzling science and unimaginably exotic locations; love, music, and politics; time travel, controversy, exploding stars, colliding galaxies...and aliens! This is a film for anyone who has ever looked up and wondered.

What made The Farthest special, to me, was including the diverse array of people responsible for the program, starting from its inception in the early 1970s. In a way, the film tells their stories—we see them getting older with the project, as the spacecraft, too, become “older” and continue their journeys. Do you think the Voyager story becomes richer and “ages better” as the years pass? Why did you think it was important to tell the stories of the people?

Reynolds: Perhaps there’s some anthropomorphism and nostalgia in the story of a tiny plucky 1970s spacecraft, sent on a one-way mission of exploration, never to return. Perhaps because we never again attempted such an audacious mission, to slingshot one spacecraft around four giant unknown planets, it has a special place in our hearts. Perhaps from the vantage point of time we can see clearer the ambition and audacity of what these scientists and engineers dreamed up, of what they achieved. I don’t know, but I do know that people love Voyager. They really connect with “The little spacecraft that could!”

In terms of the characters, science can be intimidating so I knew it would be important to express the story through the enthusiasm and personal involvement of our compelling cast of characters. We took our time in each interview, time to draw out each personality; their humanity, humor, and honesty, in order to talk to the human heart and poetic searching. I was moved and honored by how amazing and generous and deeply involved in the adventure our contributors were. [I was also moved by] how emotionally invested they were in Voyager, and how prepared they were to share that love and feeling with us and the world. The study of science, though based on facts and observable events, is not cold and indifferent. It is full of hope and joy and enthusiasm and love.

Another thing I felt that was subtly addressed (but yet very well addressed) was the inclusion of women and more diverse scientists/workers as the program unfolded. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, women were really still an oddity in scientific fields. As far as diversity is concerned, how do you think that further contributes to the Voyager legacy?

Reynolds: We made a very deliberate decision and a conscious effort to include as many women contributors as we could. There were many women at the heart of the Voyager mission and story, and though they may not have been team leaders at the time of launch, they have gone on subsequently to hold very senior NASA and space science roles, such as Linda Spilker, project scientist for Cassini; and Carolyn Porco, imaging team leader on Cassini, and all the women we speak to in the film are such amazing communicators, so open and funny and honest. The audience really responds very strongly to them. Along with myself, our core creative team also contains many women—producer Clare Stronge, line producer Zlata Filipovic, cinematographer Kate McCullough, archive researcher Aoife Carey, and production manager Siobhan Ward—so it was a natural path for us to take, to be fully inclusive. To present women being amazing scientists and engineers as a normal, unremarkable fact of life mattered hugely to us.

At one film festival a scientist approached me in tears, to say how validated she felt by the film’s inclusion of so many women.

There were sequences in The Farthest that underscored the fact that, for the first time, humanity was visiting strange new worlds. A favorite scene of mine was when Voyager 2 was leaving Saturn, and the Pink Floyd song “Us And Them” is playing; the imagery of Saturn along with the epic music had such an “otherworldly” (pardon the pun) feel. It really captured a certain mood of that era (the late 1970s and early 1980s). Were the music/imagery combinations intentional?

Reynolds: I really love that scene too—looking back and seeing the shadow of Saturn fall across the rings, and realizing we are for the first time “on the other side of Saturn!” and how the song chimes with Carolyn Porco’s thoughts: “All of planetary exploration is a story about longing.” The music fills one with that awe and ache.

| “I love the madness of the Golden Record. How would we communicate with aliens, were we to ever encounter any?” |

The scene though does generate a lot of debate, particularly with men, along the lines of “Great to see The Floyd in there, but was it the right Floyd song to use?!” All the scenes with commercial tracks in the film were designed to push the story and emotion forward, and also to anchor us in time. In my mind, Voyager having left in 1977, had not updated its record collection, so it was stuck in musical time! So all the tracks—as diverse as Floyd, Gallagher and Lyle and The Carpenters—were drawn from before 1977. With the notable exception of (though it sounds 1970s) the beautiful closing song “The Race” by Archer Prewitt, with its haunting lyrics “We won the race, we’ve claimed our place, forever cold and lost in space,” which was part of the genesis of the film when I heard it on a lonely car journey in the rain, driving from Belfast to Dublin, over ten years ago.

Something else I felt was moving about The Farthest was how it paid tribute not to just Carl Sagan (who undoubtedly did contribute a lot to the program), but also to lesser-heralded, less famous scientists such as Ed Stone, and of course many of the people who were responsible for building the spacecraft who might otherwise become a footnote in space history. Did you have any favorite contributors to the documentary, and why?

Reynolds: That’s too hard, that’s like asking a parent to choose a favorite child! I love and admire them all! They gave so much of themselves to the mission, and to us, in allowing their stories to be told, and being so open and generous with their time and emotions and memories and experiences. It was so important to us to tell the story firsthand through the scientists and engineers who actually designed, built and flew the mission, so trying to talk to as many of them in-depth about their contribution was vital.

Producer Clare Stronge also did all the initial research to find all the characters that would tell the story, and she spent so much time getting to know all these wonderful people, and sharing our vision for the film. We wanted to express the human heart of the mission. We wanted to truly communicate, without jargon—not to dumb down the science, but more to really reach a wide audience and have them share in the glory of Voyager’s adventure. When we got to filming, each interview was more than three hours long, to really reach into the depth of their experiences, and we created a relaxed atmosphere where the feeling of being filmed would hopefully fall away and we could just chat naturally. We could have made ten films with the richness of the stories told.

The Voyager Golden Record, a collection of sounds, greetings, songs, and images summarizing our planet, is also discussed at length in The Farthest. To some, the idea of putting a disc of images and songs on a spaceship might seem utterly crazy, even if there’s a remote chance one day, an extraterrestrial might find it. Do you think a “Golden Record” could fly on a spacecraft in today’s day and age?

Reynolds: One commentator described the film as “partly about the desire to know; partly about the desire to want to be known.” I love the madness of the Golden Record. How would we communicate with aliens, were we to ever encounter any? What would we want them to know about us? Why does it matter that they know about us? It’s a little crazy, but it really does matter to us, that someone, far off perhaps in space and time, knows we were once here. Long after our Sun becomes a red giant and the Earth has ceased to exist, Voyager and its Golden Record will still be out there circling the Milky Way, and could well in time become the only remnant of our existence. That is mind-blowing and humbling.

Could it work today? What is certain is that today it wouldn’t be an idiosyncratic collection curated by a small team who freely chose the music and greetings to go aboard. It would be huge worldwide committees—guaranteeing representation for all cultures, and there would be voting by the public on what music to include, and corporations paying for their logos and products to be featured. Instead of the limited space for data that the Golden Record had, there would be a key drive containing billions of pictures and films and information. Would that tell an alien more about us than Voyager’s 90 minutes of selected music, for example? I’m not sure it would...

Pale Blue Dot: A tiny blue pixel in a shaft of sunlight on the right of this image denotes the Earth as viewed by Voyager 1 in 1990. (credit: NASA/JPL) |

Lastly, what is your favorite image (if you can choose just one) from the Voyager program, and why?

Reynolds: Can I choose two? I have quite a few favorites! The famous Pale Blue Dot image obviously, is deeply moving. When we contemplate this image that Voyager 1 took from nearly four billion miles away, it really evokes a deep perspective shift in our understanding of our place in the Universe. We are so tiny, a mote of dust in a sea of cosmic night. The film tries to explore these ideas in a poetic questioning of our humanity, our responsibility and place in the Universe...asks us to turn our eyes anew toward our fragile home, to look at it from a distance, and perhaps see more clearly the amazing and rare jewel we live upon; a vista that could perhaps wake us from our nihilistic slumber before we destroy the only planet we know for certain, in this limitless and unbounded Universe, that supports life.

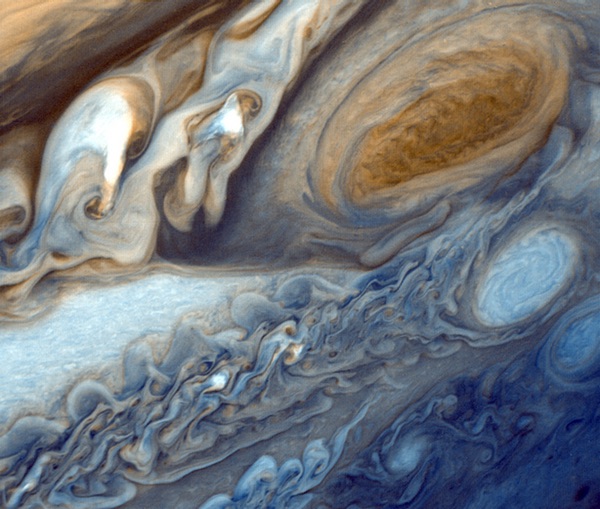

My other favorite is of Jupiter: a glorious painterly swirl of color and texture, and so very beautiful. I used this image as a visual reference in pre-production, in terms of the colors and visual palate of the film—the chromes, the blues, the oranges—and also kept it on my phone to show any willing stranger, “Look! Look at the magnificence of what Voyager saw!”

This close-up of swirling clouds around Jupiter’s Great Red Spot was taken by Voyager 1. It was assembled from three black and white negatives. (credit: NASA/JPL) |

The Farthest: Voyager in Space is available on iTunes and Amazon. It airs November 15 at 10pm Eastern/9pm Central on PBS, and will stream online via PBS from November 16-30.