US space policy, organizational incentives, and orbital debris removalby Brian Weeden

|

| The US government has a mixed record of implementing the recommendations from scientists on dealing with space debris. |

Scientists studying the space debris problem have concluded that minimizing the creation of new space debris, also known as debris mitigation, was a necessary first step. Most recently, scientists have concluded that remediation, the process of reversing or stopping damage, will be necessary in space as well. The primary remediation mechanism is the removal of existing space debris, particularly the most massive objects residing in low Earth orbit (LEO) that are the biggest source of future space debris. It may also be necessary to remove portions of the smaller space debris population between one and ten centimeters in size that are currently untracked and pose a significant hazard to active satellites. Still others have proposed using just-in-time collision avoidance (JCA) to help prevent debris-on-debris collisions from generating additional debris.

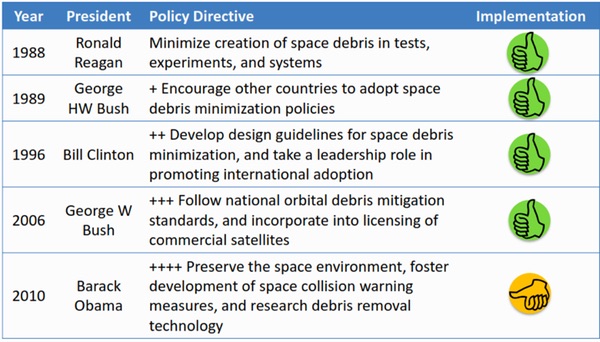

The US government has a mixed record of implementing the recommendations from scientists on dealing with space debris. Since the space program began in the mid-1950s, most presidential administrations have issued national space policies through presidential decision directives (PDDs), which are developed as the result of an interagency process that brings together multiple departments and agencies that have equity in a particular policy area. These PDDs have gradually included more of a focus on space debris, and directed the executive branch to take specific actions to deal with space debris. For the most part, these actions have been implemented, with the exception of the directive to implement the development of active debris removal (ADR) capabilities in the 2010 National Space Policy issued by the Obama Administration.

This article attempts to explain why the US government has only taken small steps toward implementing the ADR policy. The first section provides an overview of how US national policy on space debris evolved across multiple presidential administrations. The second section looks at the implementation, or lack thereof, of the space debris elements of the most recent national space policy issued by the Obama Administration in 2010. The third section examines the economics of space debris, and explains why this is a problem the private sector cannot solve on its own. The fourth section uses concepts from the field of public policy to explain why there has not been much progress on ADR. The fifth section outlines steps Congress and the Trump Administration can take to better align organizational incentives within the executive branch in order to make progress on ADR.

Evolution of US national policy on space debris

Since the 1960s, there has been a slow but continuous evolution in understanding of the threat posed by space debris. The scientific research on space debris was driven mainly by the need to understand space environmental risks for high-profile programs such as human spaceflight. Eventually, a combination of factors, including progress in the scientific understanding and unexpected external events, led to space debris being included in presidential policy directions on space. The following sections trace this evolution from the 1960s to the 2010s.

Space was not a pristine environment before humans began launching spacecraft into orbit. The solar system is home to many asteroids that, in turn, created an untold number of smaller fragments, called meteoroids, through collisions with each other. Occasionally, meteoroids re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere and become visible meteors streaking across the sky.

Beginning in the 1950s, NASA started to study the potential hazards present in the natural space environment, including meteoroids, as part of preparations for the American human spaceflight program. The studies included theoretical work, ground-based observation of meteors, hypervelocity impact testing on the ground of spacecraft, and flight experiments to measure the rate of actual impacts. These studies concluded that the meteoroid environment posed a real, but relatively small, risk for most spacecraft.

| The heightened awareness created by these events, and NASA’s work, led to the first official policy statement on space debris in 1988. |

In the late 1960s, some within NASA began to wonder if scientific study should begin to shift to assessing the potential hazard from human-generated space debris. By the end of 1968, there had already been more than a dozen on-orbit fragmentations of satellites or rocket bodies, which created hundreds of pieces of space debris. However, the few analyses that were done concluded that since many of the fragments were too small to be tracked by the North American Aerospace Defense Command’s (NORAD) tracking network, the increased risk was “inconsequential”.

By the mid-1970s, there was renewed interest in studying orbital debris as a possible hazard, in part due to the experiences with longer-duration missions such as Skylab. The interest lead NASA scientists Don Kessler and Burton Cour-Palais to publish an influential paper that predicted significant growth in the population of human-generated space debris, and hence the collision hazard to spacecraft. The major prediction of their work was that by the year 2000, the density of space debris objects would reach the point where collisions would create new space debris faster than it was pulled out of orbit through atmospheric decay. Eventually, this would lead to exponential growth in the debris population and human-generated space debris, posing more of a hazard to spaceflight than the natural meteoroids. Kessler and Cour-Palais concluded that the only effective way to prevent this scenario was to re-enter large objects at the end of their useful life and minimize on-orbit explosions and fragmentations.

During the 1980s, the work of Kessler and Cour-Palais, combined with other high-profile events, led to increased attention on space debris. According to Kessler, NASA officially created an orbital debris team in 1979 with an initial budget of $70,000 and only one full-time member. Studies continued, as did on-orbit explosions and fragmentations. Three high-profile events in the mid-1980s boosted recognition of the problem significantly: NASA’s decision to build Space Station Freedom; the Department of Defense’s (DOD) anti-satellite (ASAT) test that destroyed the US Solwind satellite and created hundreds of pieces of debris; and the 1986 explosion of a French Ariane rocket stage that created hundreds more. By 1987, NASA was conducting research and organizing conferences in cooperation with Western Europe on the importance of minimizing the creation of debris.

The heightened awareness created by these events, and NASA’s work, led to the first official policy statement on space debris. In 1988, President Ronald Reagan announced a new national space policy, which revised his previous national space policy from 1982. The revised national space policy included a directive that stated:

“…all space sectors will seek to minimize the creation of space debris. Design and operations of space tests, experiments and systems will strive to minimize or reduce accumulation of space debris consistent with mission requirements and cost effectiveness.”

The 1988 Reagan National Space Policy also directed an interagency working group to develop recommendations on the implementation of the space debris policy, which culminated in a National Security Council report on space debris in February 1989.

Subsequent national space policies continued to mention the need for addressing the threat of space debris. In 1989, the George H. W. Bush Administration issued a new national space policy that reiterated the same statement on space debris from the 1988 Reagan policy, with an additional focus on encouraging all spacefaring countries to minimize space debris:

“…The United States government will encourage other space-faring nations to adopt policies and practices aimed at [space] debris minimization.”

The George H.W. Bush National Space Policy led to the creation of bilateral working groups between NASA and space agencies in Europe, Russia, and Japan, which were later merged into the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee (IADC) in 1993.

In the 1990s, the Clinton Administration continued and expanded a policy focus on space debris. The 1996 Clinton Administration’s national space policy included the same language as the George H.W. Bush Administration’s policy, but added a new focus on developing intra-governmental guidelines to minimize the creation of space debris, and working to promulgate those guidelines internationally:

The United States will seek to minimize the creation of space debris. NASA, the Intelligence Community, and the DOD, in cooperation with the private sector, will develop design guidelines for future government procurements of spacecraft, launch vehicles, and services. The design and operation of space tests, experiments, and systems will minimize or reduce accumulation of space debris consistent with mission requirements and cost effectiveness.

It is in the interest of the U.S. Government to ensure that space debris minimization practices are applied by other spacefaring nations and international organizations. The U.S. Government will take a leadership role in international fora to adopt policies and practices aimed at debris minimization and will cooperate internationally in the exchange of information on debris research and the identification of debris mitigation options.

| As a result of both the Clinton and Bush Administration policies, progress on international debris mitigation guidelines continued. |

The space debris mitigation language in the Clinton National Space Policy reflected work that was already going on within the US government. By 1995, NASA had already prepared a set of draft orbital debris mitigation guidelines. The draft NASA guidelines became the draft US Government Orbital Debris Mitigation Standard Practices, which were approved by the White House in 2001 after consultations with industry. The debris mitigation standard practices were implemented for US government space activities through departmental guidance and regulation, and for US.commercial space activities through pre-launch licensing processes.

In the 2000s, the George W. Bush Administration continued the policy focus on debris mitigation guidelines established by the Clinton Administration. The 2006 George W. Bush National Space Policy included much of the same language as the 1996 Clinton National Space Policy, but added more focus on preserving the space environment and including debris mitigation requirements in the licensing of US commercial space activities:

Orbital debris poses a risk to continued reliable use of space-based services and operations and to the safety of persons and property in space and on Earth. The United States shall seek to minimize the creation of orbital debris by government and non-government operations in space in order to preserve the space environment for future generations. Toward that end:

Departments and agencies shall continue to follow the United States Government Orbital Debris Mitigation Standard Practices, consistent with mission requirements and cost effectiveness, in the procurement and operation of spacecraft, launch services, and the operation of tests and experiments in space;

The Secretaries of Commerce and Transportation, in coordination with the Chairman of the Federal Communications Commission, shall continue to address orbital debris issues through their respective licensing procedures; and

The United States shall take a leadership role in international fora to encourage foreign nations and international organizations to adopt policies and practices aimed at debris minimization and shall cooperate in the exchange of information on debris research and the identification of improved debris mitigation practices.

As a result of both the Clinton and Bush Administration policies, progress on international debris mitigation guidelines continued. The IADC continued to develop technical space debris mitigation guidelines, and in September 2007 published the IADC Space Debris Mitigation Guidelines, which represented the consensus views of the technical experts from eleven national space agencies. In parallel, a working group within the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (UNCOPUOS) negotiated a simplified version of the IADC guidelines, which were endorsed as voluntary measures by the full United Nations General Assembly in December 2007.

While the efforts of the IADC and UNCOPUOS to develop mitigation guidelines were successful, incidents in space continued to increase the amount of space debris. On January 11, 2007, China conducted an ASAT test that destroyed one of its own weather satellites at an altitude of around 860 kilometers. On February 9, 2009, the Iridium 33 satellite, an American commercial satellite, collided with Cosmos 2251, a dead Russian military satellite, at an altitude of around 800 kilometers. Taken together, the two events created more than 5,000 pieces of trackable space debris (larger than 10 centimeters) in what was already the most highly congested region of Earth orbit.

The massive amount of orbital debris created by the 2007 Chinese ASAT test and the 2009 Iridium-Cosmos collision effectively reversed the reduction in space debris resulting from the debris mitigation guidelines, and prompted research to look beyond just mitigation to remediation of the space environment. New studies done by NASA and other agencies concluded that space debris remediation, mainly through removal of large space debris objects from LEO and GEO, was the only practical method to reduce the long-term collision threat to operational satellites.

The on-orbit events and studies prompted the Obama Administration to increase the focus on preserving the space environment in its national space policy. The 2010 National Space Policy stated that the United States considers the sustainability of space to be vital to its national interests and added a new section on “Preserving the Space Environment and Responsible Use of Space” that contained the language from the George W. Bush policy but added specific policy direction on space collision warnings and active debris removal (ADR):

Preserve the Space Environment. For the purposes of minimizing debris and preserving the space environment for the responsible, peaceful, and safe use of all users, the United States shall:

- Lead the continued development and adoption of international and industry standards and policies to minimize debris, such as the United Nations Space Debris Mitigation Guidelines;

- Develop, maintain, and use space situational awareness (SSA) information from commercial, civil, and national security sources to detect, identify, and attribute actions in space that are contrary to responsible use and the long-term sustainability of the space environment;

- Continue to follow the United States Government Orbital Debris Mitigation Standard Practices, consistent with mission requirements and cost effectiveness, in the procurement and operation of spacecraft, launch services, and the conduct of tests and experiments in space;

- Pursue research and development of technologies and techniques, through the Administrator of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the Secretary of Defense, to mitigate and remove on-orbit debris, reduce hazards, and increase understanding of the current and future debris environment; and

- Require the head of the sponsoring department or agency to approve exceptions to the United States Government Orbital Debris Mitigation Standard Practices and notify the Secretary of State.

Foster the Development of Space Collision Warning Measures. The Secretary of Defense, in consultation with the Director of National Intelligence, the Administrator of NASA, and other departments and agencies, may collaborate with industry and foreign nations to: maintain and improve space object databases; pursue common international data standards and data integrity measures; and provide services and disseminate orbital tracking information to commercial and international entities, including predictions of space object conjunction.

| The massive amount of orbital debris created by the 2007 Chinese ASAT test and the 2009 Iridium-Cosmos collision effectively reversed the reduction in space debris resulting from the debris mitigation guidelines. |

The historical record outlined above shows a slow but steady increase in policy directives focused on space debris. These directives were largely developed in response to, rather than in anticipation of, real-world activities. The policy directives also reflected work already being done by scientists and the organizational interests of the departments and agencies participating in the interagency policy process. Thus, they are more of a codification of interests and concerns rising from the bottom up rather than a function of top-down directives from elected officials. However, that level of organizational buy-in did not mean the policy directives were always implemented, particularly in the case of the Obama Administration’s 2010 National Space Policy, which the next section will examine in more detail.

Implementation of the space debris measures and the 2010 National Space Policy

The implementation track record of space debris policy goals established in the Obama Administration’s 2010 National Space Policy has been mixed, particularly on the new additions of space collision warning measures and ADR. The following sections discuss the progress, or lack thereof, on three main elements of the 2010 National Space Policy on space debris: space collision warning measures, international initiatives, and the development of ADR technology.

The most progress has been made on the space collision warning measures. In 2010, United States Strategic Command’s (USSTRATCOM) Joint Space Operations Center (JSpOC) at Vandenberg Air Force Base expanded its screenings for potential on-orbit collisions to include all operational satellites, including commercial and foreign satellites. Under the new SSA Sharing Program, the JSpOC began providing warnings of close approaches (conjunctions) directly to all satellite operators, and created a process for operators to get more detailed data on conjunctions in order to make decisions about maneuvers to reduce the risk of a collision. In 2016, that mission was transferred to the newly-reconstituted 18th Space Control Squadron (18 SPCS). By the end of 2016, the SSA Data Sharing Program was providing close approach warnings on nearly 1,500 active satellites to 285 organizations, resulting in 128 avoidance maneuvers to reduce the risk of collisions.

However, the Obama Administration was unable to go beyond the DOD’s efforts and create a more holistic space traffic management (STM) effort with civil agencies. Shortly after issuing the 2010 policy, the Obama Administration convened an interagency group to develop recommendations for STM, and specifically to shift authority for SSA data sharing and providing close approach warnings from the DOD to a civil agency. However, after several years of discussions, no decisions were reached, mainly due to national security concerns, debates over which civil agency would be the best choice, and how it would coordinate with the other agencies that have oversight authorities over private sector space activities.

| The DOD’s reluctance to move forward on ADR is understandable, given its organizational interests. While it has the largest space budget of any governmental entity and is extremely reliant on space, cleaning up the space environment is not one of its core missions. |

Limited progress has also been made in the international measures directed by the 2010 National Space Policy. The United States has focused its multilateral diplomatic efforts to address space debris and the space environment mainly on participation in the Working Group on the Long-term Sustainability (LTS) of Outer Space Activities under the Scientific and Technical Subcommittee (STSC) of UNCOPUOS. The Working Group was created in 2010 to examine and propose measures to ensure the safe and sustainable use of outer space for peaceful purposes and for the benefit of all countries. In June of 2016, the Working Group on LTS reached consensus on an initial set of 12 voluntary guidelines for enhancing space sustainability based on existing best practices. The guidelines endorsed by the LTS Working Group include promoting sharing of information on space debris and investigating measures to manage the space debris population. The LTS Working Group plans to continue to discuss 16 additional guidelines, with the hope of reaching consensus in 2018.

The United States has also engaged in a series of bilateral engagements on SSA data sharing. Following the 2010 National Space Policy, USSTRATCOM was given authority to lead negotiations with commercial satellite operators and foreign governments on data-sharing agreements. As of October 2017, USSTRATCOM had signed agreements with 13 foreign governments, two international organizations, and more than 60 commercial entities. These bilateral agreements provide the policy framework for which the United States can exchange SSA data with foreign governments and commercial satellite operators to support both space debris monitoring and collision warning, and national security needs.

However, it is the third main directive of the 2010 National Space Policy—developing ADR technology—where there has been little to no progress by the DOD and NASA. According to a US government participant in a workshop convened by National Research Council in 2011, a space debris remediation plan was discussed (but not implemented) in the 2010 National Space Policy due to concerns over costs, lack of specific agency responsibility, and political concerns over the weapons-like concern of some of the ADR techniques.

Initially, the DOD showed significant motivation on ADR. In September 2009, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) announced a study known as “Catcher’s Mitt” to examining the issues and challenges with removing man-made debris from orbit. The study, which concluded in 2011, included a Request for Information for possible technical approaches and economic assessments, and an international workshop co-hosted by DARPA and NASA in December 2009. However, no follow-up actions were taken, despite the study’s conclusion that US military should pursue ADR.

The DOD’s reluctance to move forward on ADR is understandable, given its organizational interests. While it has the largest space budget of any governmental entity and is extremely reliant on space, cleaning up the space environment is not one of its core missions. Furthermore, the US military has historically been very sensitive to international perceptions that it is weaponizing space, not necessarily because it does not want to do so but because of the political impact such perceptions may have on domestic support in Congress and international support from its allies. Thus, the US national security space community has strong concerns that any military-backed initiative for ADR may stimulate comparable programs by others in response or create geopolitical complications.

The DOD is also shifted its focus over the last few years away from concerns about space environmental threats and towards hostile counterspace threats. The 2007 Chinese ASAT test was just one in a string of tests since 2005 that appear to be aimed at developing at least two different ASAT weapons systems, and a 2013 test at GEO was particularly alarming to some in the US national security community. In addition, there is evidence that Russia has reactivated some of its own ASAT programs that were left fallow after the end of the Cold War, and may have used counterspace jamming capabilities in its military intervention in Ukraine. As a result, the DOD has focused a significant amount of attention to addressing the potential threat from the counterspace capabilities of potential adversaries, and less on space debris.

NASA has had some organizational support for ADR, but it’s faced challenges from both the budget and NASA’s organizational structure. Three different NASA field centers—Ames Research Center in California, Johnson Space Center in Texas, and Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland—have all indicated a strong interest in being the “center of excellence” for space debris within NASA, partly because they saw it as a potential source of additional funding. Each of the three centers has a different focus, largely as a function of its broader expertise and mission set, and are competitive with each other to a degree on the space debris issue.

Partly as a result of this competition between centers, and partly due to broader budget constraints, NASA’s budget submissions reflect an increased rhetorical focus on space debris, but little actual monetary commitment. The term “space debris” did not even appear in NASA’s fiscal year 2009 (FY09) budget estimate, as it was considered to be a small part of operations and protection for both the Space Shuttle and the International Space Station (ISS). Beginning in FY10, NASA included in its budget documents a specific reference to space debris, and outlined efforts to conduct scientific studies to characterize the near-Earth space debris environment, assess its potential hazards to current and future space operations, and identify and implement means of mitigating its growth, but did not provide a dedicated budget line for doing so.

| While the US government has made progress on implementing space debris collision warning measure and fostering international discussions, minimal progress has been made on developing ADR technology. |

Since 2011, NASA has invested a small amount of money in research and development for ADR technology. A NASA Innovative Advanced Concepts (NIAC) Phase I award was given out in 2011 to study Space Debris Elimination. Throughout 2011 and 2012, NASA began to review proposals for ADR concepts, culminating in a $1.9 million contract to a Star Technologies, Inc., in 2013 to develop the technology for an electrodynamic tether that could remove debris from LEO, but the funding was not continued past FY14. In 2016, NIAC awarded another Phase I contract to the Aerospace Corporation to develop the concept for its two-dimensional “brane” spacecraft for orbital debris removal, which was followed up with a Phase II contract in 2017.

While these small research and development grants are a step in the right direction, NASA has also decided to set strict limits on its investment in carrying research and development of ADR technologies forward. In June 2014, NASA formally adopted a policy to limit its ADR efforts to basic research and development of the technology up to, but not including, on-orbit technology demonstrations. It is believed that the main reason for this limitation was an unwillingness by NASA to take on a potentially costly major new initiative without additional funding from Congress.

Figure 1. Summary of US national space policy on space debris and its implementation. |

Thus, while the US government has made progress on implementing space debris collision warning measure and fostering international discussions, minimal progress has been made on developing ADR technology. The initial interest shown by the DOD has waned, and NASA has decided it will not pursue R&D of ADR technologies beyond some very limited low-level efforts. The next section discusses the economics of space debris, and why government involvement in ADR is critical for making progress.