Seeking regulatory certainty for new space applicationsby Jeff Foust

|

| “If we don’t do Article VI right, it can have a drag effect, a chilling effect on our technology development,” Gold warned. |

One obstacle such non-traditional missions have faced in the United States is regulatory uncertainty. The FCC oversees communications satellites, placing requirements on them as part of the licensing process, while NOAA does the same for Earth observation satellites. The FAA handles launches and reentries, but not what takes place in between. Everything else falls into a gray area, with no single agency clearly responsible.

Such oversight is needed, most argue, because of language in Article VI of the Outer Space Treaty. “The activities of non-governmental entities in outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, shall require authorization and continuing supervision by the appropriate State Party to the Treaty,” that section of the 50-year-old treaty states.

What such “authorization and continuing supervision” means is left up to each country, and just how that applies in the US for those non-traditional applications is unclear. “No two words in the English language make me more nervous than ‘continuing supervision,’” said Mike Gold, vice president for regulatory issues at Maxar Technologies—the new name of MacDonald, Dettwiler and Associates after its merger with DigitalGlobal—and chairman of the FAA’s Commercial Space Transportation Advisory Committee, at a panel discussion last month in Washington organized by the Space Transportation Association.

“If we don’t do Article VI right, it can have a drag effect, a chilling effect on our technology development,” he said. “Or, if we do get it right, it can really bolster this industry, and bolster the US.”

Other companies represented on the panel also sought clarity on how to address oversight for emerging space applications. “What is the regulatory clarity? You need to understand that to be able to assess the risks, quantifying the risks, of going forward,” said Jennifer Warren, vice president of technology policy and regulation at Lockheed Martin. “We’ve been very straightforward with the executive branch over the last number of years that we would really like to see a clear designation of a supervisory authority under Article VI.”

“Ensuring the US commercial space industry remains a global leader is contingent on a streamlined, responsive, and transparent process under a consolidated regulatory authority that will ultimately meet the requirements of Article VI,” said MaryLee Pollitt, trade compliance analyst at Sierra Nevada Corporation.

| “You might expect that we might have some Article VI challenges,” said Astrobotic’s Hendrickson. “Thankfully, I can say that it’s actually quite the opposite: we don’t have regulatory hurdles at the moment.” |

But even without that regulatory clarity, companies developing such non-traditional missions have been working through the existing regulatory process with some success. Last year, Moon Express announced that it won a payload review from the FAA for its first lunar lander mission, going through the existing review process for commercial launches and voluntarily providing additional information to demonstrate its compliance with aspects of the Outer Space Treaty. That approval, while a milestone for the company, is widely seen as a one-off process and not a precedent for other ventures.

Astrobotic, another company planning commercial lunar landers, is working through similar regulatory issues. “You might expect that we might have some Article VI challenges,” said Dan Hendrickson, vice president of business development at Astrobotic. “Thankfully, I can say that it’s actually quite the opposite: we don’t have regulatory hurdles at the moment.” He thanked the FAA’s Office of Commercial Space Transportation (AST) for providing guidance to the company as it goes through a mission approval process for its first lander.

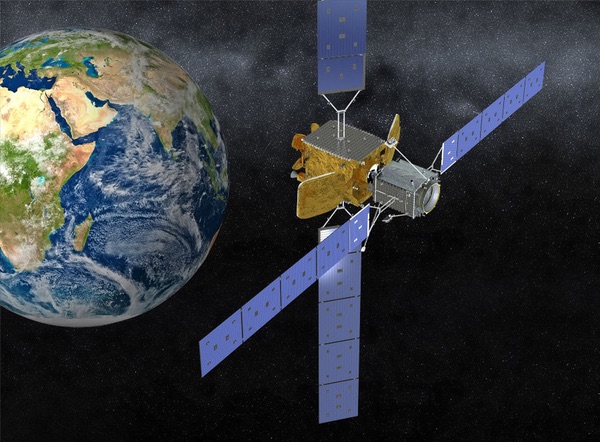

Orbital ATK, meanwhile, is working through regulatory processes for the company’s first Mission Extension Vehicle, scheduled for launch in about a year to attach to, and extend the life of, commercial communications satellites.

“We’ve had a very positive experience with every department and agency. They all wanted to help, they have all been leaning forward to make this happen,” said company vice president Jim Armor.

It’s not been a completely smooth process, though. “We expected some confusion over the last six or seven years, and we found it,” he said. The company found, for example, that that it needed to get a NOAA license for commercial remote sensing because cameras on its vehicle, intended to support satellite servicing, could also image the Earth in that process. Orbital ATK eventually got its mission authorization to comply with Article VI through the FCC, which licenses the communications for the mission and also approved its orbital debris mitigation plan.

Armor said that while they have been able to “muddle through” under this approach, a recent change by NOAA in oversight of “non-Earth imaging” by satellites, including of other satellites, has created some complications. “Our operations plans are not quite in disarray, but we are having to go through them again,” he said.

No companies, though, have argued that a lack of clear authority among agencies to provide the requisite oversight of non-traditional space missions have blocked their plans. If companies are, at the very least, able to muddle through under the current system, is regulatory reform, in the form of giving that authority to a single agency, absolutely needed?

Yes, both executives and government officials argued during the panel discussion. “The current process is broken,” said George Nield, associate administrator for commercial space transportation at the FAA. “There is no government department or agency that is clearly identified as having responsibility to authorize and continuingly supervise.”

When it comes to non-traditional space applications, “all of the agencies involved are trying to figure out how to make it work, what’s an interim step, what can we do for now,” he continued. “But we are clearly looking for a long-term solution, and we need that soon.”

“All of the committees and departments and agencies are trying to be helpful,” Armor said, likening it to spinning a group of plates. That effort, he said, doesn’t scale as the number of missions, by his company and others, increases. “We’re going to need a lot faster, and more often, updates and licensing agreements.”

“Clarity and predictability: these are the values that are needed, not just for operations, but for investment, for insurers,” said Gold. “Right now, we may already be behind some of the foreign competition. If you go to Luxembourg and ask how this issue is being addressed, or the UAE or the UK, there’s a clear path.”

| “The current process is broken,” said Nield. “There is no government department or agency that is clearly identified as having responsibility to authorize and continuingly supervise.” |

Nield has long made clear that he would be willing to have AST take on that responsibility for authorization and continuing supervision for non-traditional space missions. However, one bill in the House, the American Space Commerce Free Enterprise Act, would instead give that responsibility to the Department of Commerce’s Office of Space Commerce, which today has only a few staff members. That bill was approved by the House Science Committee in June, but has yet to be taken up by the full House.

Panelists didn’t directly address that bill, but argued they thought that AST, and not Commerce, should have that responsibility, based on its experience with payload reviews in general.

“I’m really happy with the FAA commercial space transportation approach,” Armor said. “I think growing that in the Department of Transportation makes sense.” He added that, speaking as chairman of the commercial space committee of the Aerospace Industries Association, that group endorsed assigning that authority to the FAA.

Astrobotic’s Hendrickson also backed keeping that regulatory authority in the FAA. “If we were to change that, by perhaps moving that authority on Article VI to another government agency as far as the interface with industry is concerned, that could create quite a bit of turmoil and questions among our payload customers around the world,” he said.

“Among industry, it’s become pretty clear that AST, giving its forward leaning towards enabling industry, is a great place to be,” Warren said, adding that was true whether AST remained within the FAA or, as some have suggested, moving it out of the agency into a separate office under the Secretary of Transportation, where it existed for a decade before being subsumed within the FAA in the mid-1990s.

“The mindset and culture that has enabled this industry to get where it is today is the culture we want to see for the new commercial space applications,” she said of AST.

Nield said that authority could be granted through legislation, including as a provision of the next overall reauthorization of the FAA. It could also, he said, be done simply through executive order, such as when President Reagan did in the 1980s when he gave oversight of commercial launch to the Department of Transportation.

“What if we’re not able to get this resolved in the near future? What happens then?” he asked. Companies could slow down their projects, he said, or move ahead and accept the risk that regulatory issues could block their projects, possibly late in development. Or, he said, companies could move to countries that provide more regulatory certainty. “That would be a really sad day for US leadership in space.”