How to reduce US space expenses through competitive and cooperative approachesby Takuya Wakimoto

|

| One approach to achieve cost reduction in the US space policy would be international cooperation. |

One obstacle of setting Acceptable Reasons for space policy is its “high risk, high cost, and long payback periods” architecture (Vedda, 2009, p.99). This structural limitation is like that in science and technology policy in general that is often less appealing for politicians to pursue: politicians and decision-makers tend to seek short-term results, not visionary long-term goals (Neal, Smith, & McCormick, 2011). One way to ameliorate this structure is to improve returns on investment. Some scholars examined NASA’s R&D contribution to the private economy and argue economic importance of space activities (Mathematica, 1976; Hertzfeld, 1992). Yet, returns from space are often vague (Bush, 2004) and often invisible in short run. So, what can be done to convince more politicians to support and sustain US space programs? One answer is cost reduction. Tackling the cost burden will change the dynamic of high-risk/low-return architecture and will enhance the competitiveness of space policies.

One approach to achieve cost reduction in the US space policy would be international cooperation. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) published a report in 1994 suggesting the two major reasons for the high cost structure of NASA: high fixed costs and funding late in a project’s life cycle (CBO, 1994). The report further recommends that international cooperation in space would enable cost sharing with other spacefaring countries. The insights of one historian, John Logsdon (2005), back the idea of inefficiency in space policy. Although each country has its own space programs, some of the programs are similar to other countries as well. Therefore, collaborating, sharing, and cooperating with global partners could be one approach to cutting cost of US space programs.

Today, more than 50 counties own and operate satellites (Harrison & Cooper, 2016), and each country pursues similar goals that of the US, such as space exploration, Earth science research, military operations, and economic growth. Opportunities for the US to share costs by international cooperation are numerous (Gibbs, 2012). A fundamental problem of international cooperation, however, is a juggling of military and civil/commercial technology. Military technology should be confined to one’s own country, or shared only with close allies. Moreover, it may not be desirable to share economic returns with other countries. These criteria limit the potential of the US to create partners in space. Thus, how do we balance competitive and international cooperation approaches in space?

In this respect, the purpose of this study is to identify how US could reduce overall space expenses by balancing competition and international cooperation in space. The overarching goal of balance is to sustain US future space programs under severe budget pressures. First, the paper briefly analyzes the US, Russia, China, ESA, and Japan’s latest space policies. Those five countries’ space policies are the compared to identify potential areas of synergy (international cooperation approach) and those areas that are less conducive to cooperation (competitive approach). This leads to recommendations about how the US should balance competitive and international cooperation in space.

Nation policy analysis

US space policy

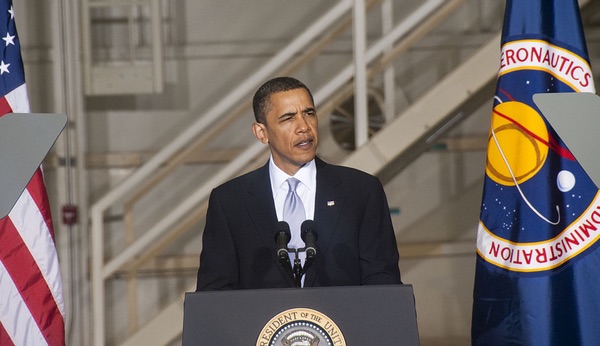

Since the current Trump administration has not yet released a new overarching national space policy, current national space policy (NSP) is the one implemented by the Obama Administration in 2010. Obama’ NSP was different from President George W. Bush’s policy especially in national security, human space exploration programs, and international cooperation. Obama placed less emphasis on the military aspect of space (compared to other objectives) than his predecessor. The Constellation program, a human spaceflight program developed by Bush aimed at returning to the Moon as a stepping-stone to the Mars and beyond, was cancelled (Obama, 2010). The policy placed more emphasis on international cooperation to promote sustainable space environment and peaceful use of space. The Secure World Foundation’s editor Victoria Samson argues the NSP 2010 was an effort to take a leadership role in encouraging the global community to carry out responsible behavior in space (Samson, 2011). Additionally, the NSP 2010 also indicated a strong interest in commercial sector to develop both crew and cargo vehicles.

Russian space policy

The latest official Russian space policy paper, Major provisions of the Russian Federal Space Program for 2006–2015, was approved in October 2005. The principal goal of this policy is to satisfy increasing demands on space technology from the government, regions, and the public community (Roscosmos, 2005). This policy was set out in two stages of milestone to achieve principal objectives: increase satellite constellations’ capability to provide socioeconomic benefits, science and security, sustaining development of competitive rockets, and space technologies (Gibbs, 2011).

| Competition among other sovereign countries is inherently inevitable. But, countries could find a way to collaborate if this effort does not degrade its own country’s living standards and national security. |

While it may not yet be officially endorsed, however, there seems to be a movement to create a new Russian space policy. According to Russian Federal Space Agency’s web site, “Strategy of development of space activities in Russia until 2030 and beyond” had been drafted in 2012 (Roscosmos, 2012). This strategy sets Russian space policy’s general provisions, principles of space activities in the long-term, and a milestone of implementations. Overall strength of military capability and a protection of independence in space are especially emphasized.

Chinese space policy

In general, Chinese space policy establishment begins from a white paper issued by the Information Office of the State Council, and then finalized by announcements of high-level officials (Gibbs, 2012). Following this rule, the latest Chinese space policy seems to be publicly released on December 28, 2016, on the State Council’s website (State Council, 2016). The white paper seeks space policy as a driving force for social progress. This is not a new strategy but rather a long-standing principle that Chinese space policy has been developed through national prestige purpose and economic benefits in order to strengthen the Party (Pollpeter, 2015).

ESA Space Policy

The European Space Policy 2007 is the first and latest common political framework of space programs in EU and non-EU member states (European Space Agency, 2007). In this paper, the European Space Agency (ESA) recognizes space systems as “strategic assets demonstrating independence and the readiness to assume global responsibilities” (ESA, 2007, p.21). Thus independence, security, and prosperity of Europe are fundamental rationales for space. To achieve these goals, the policy focuses on space applications for global climate change, supplementing security and defense needs, developing a competitive space industry, investing in space science and space exploration, and securing unrestricted access to improve space technologies (ESA, 2007). Both EU and non-EU countries are recommended to follow these strategies so as to achieve unified progress in space.

Japanese space policy

In August 2008, the Japanese government renewed its Japan Basic Space Law to allow the Government to acquire military (self-defense) space capabilities. Prior to that, military use of space was deemed a violation of the country’s constitution. Thus Japanese space policy was restricted only for apparent peaceful purposes, meaning non-military applications. However, a long intergovernmental coordination, especially accelerated since North Korea’s Taepo Dong shock in 1998, bore fruit to issue new the Basic Plan for Space Policy (Basic Plan) in June 2009 (Suzuki, 2013). The Basic Plan includes military purpose of space in addition to originally pursue space goals such as to improve science and technology, achieve economic gain, and enhance situation awareness.

Deciding where to compete or to cooperate

This section further examines the five national space policies in order to identify those areas where US could cooperate versus where it should remain competitive. The study used the most common motivations of national space program suggested by Gibbs (2012) as a benchmark of comparison. Out of original nine common motivations, six motivations (hereafter referred to as Areas) were selected: Discovery/Knowledge and Understanding; Economic Growth-Job Creation and New Markets; Prestige/Leadership; Security and Defense; Education; International Relations/Rule Making. Slight modifications in the original motivations, which seemed to overlap or be ambiguous, made the classification of each national policy more intelligible. Results of comparison are shown in this chart.

The chart shows that all five countries set six Areas of national space policy except Japan, who does not have a goal involving Prestige/Leadership. In this respect, the US could seek a potential partner from among those four nations. However, there are limitations that restrict international cooperation, which involve security and economy. The fundamental ideology of a sovereign country is to maintain national security and improve living standards by building a strong economy (Coicaud & Wheeler, 2008). As a result, competition among other sovereign countries is inherently inevitable. On the other hand, countries could find a way to collaborate if this effort does not degrade its own country’s living standards and national security.

Therefore, a feasible balance whether US should take competitive or cooperative approaches could be determined by considering if the six aforementioned Areas are affected by national living standards (economy) and/or national security. An ordinal scale (low, medium, and high) is subjectively used to measure these two aspects. If, for instance, a direct impact on a national security is less, then an examined Area is scaled as “low”. Direct impact is emphasized here because decision-makers prefer short-term outcomes, and so recognized as more politically feasible. Table 1 shows a result of such taxonomy.

Table 1: Balancing Competitive and Cooperative Approaches in US Space Policy

| # | Interest Areas | Direct Impact on Living Standard (Economy) | Direct Impact on National Security | Possibility of Competitive or Cooperation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Discovery/ Knowledge and Understanding | Low | Low | Cooperation |

| 2 | Economic Growth-Job Creation and New Markets | High | Low | Competitive |

| 3 | Prestige/ Leadership | Low | Medium | Competitive and Cooperation |

| 4 | Security and Defense | Low | High | Competitive and Cooperation |

| 5 | Education | Low | Low | Cooperation |

| 6 | International Relations/Rule Making | Low | Low | Cooperation |

Table 1 indicates one competitive Area, three cooperative Areas, and two Areas where both competitive and cooperative approaches could be pursued:

- Competitive approach: Economic Growth-Job Creation and New Markets;

- Cooperative approach: Discovery/Knowledge and Understanding, Education, and International Relations/Rule Making;

- And both competitive and cooperative approaches: Prestige/Leadership and Security and Defense.

How the US should balance competitive and cooperative approaches in space?

This section attempts to indicate reasons why US should take competitive or cooperative approaches in space, along with some suggested approaches.

Competitive (domestic) strategy

Economic Growth-Job Creation and New Markets seemed to be an option less likely for the US to cooperate with other countries, thus, perhaps the only area that the US should approach independently.

| The US could use existing international communities to take a leading role to create integrated programs. US efforts to explore space could be a rationale on the surface, but the actual intention could be the cost sharing of US space programs. |

The US should seek a competitive approach in space for its domestic economy. The global space economy totaled about $323 billion and $329 billion in 2016. Seventy-six percent of these amounts were linked to commercial space (The Space Foundation, 2017). Overall US space revenue, in particular, was estimated at $43 billion in 2012 and roughly 73,000 full time employment (OECD, 2013). The space industry is a relatively new market and is expected to consistently grow. Thus, the US government should provide incentives and a regulatory environment for the US space industry to optimize its revenue.

According to a 2017 Aerospace Industries Association report, however, today’s US regulatory and policy environment is limiting space economy expansion (AIA, 2017). One example is the International Traffic of Arms Regulations (ITAR) on satellites and related technology exports. ITAR was first enacted in 1999 and relaxed in 2014 under export control reforms by the Obama Administration, yet, this regulation still restricts the US space industry from exporting while many of these technologies are said to being obsolete (AIA, 2017). Relaxation of ITAR will increase the volume of exports that will increase the learning curve effect as well as the scale of the economy. Thus eventual cost reduction through mass production could be expected. In conclusion, relaxation of regulations seems to be necessary for the US space industry to seize more from a $300 billion market.

International Cooperation Strategy

US space policy could develop international cooperation in following three Areas: Discovery/Knowledge and Understanding, Education, and International Relations/Rule Making.

Discovery/Knowledge and Understanding

Each country addresses their enthusiasm about deep space exploration by both robotic and human missions. This enthusiasm may have originated from what historian Roger Launius suggests in his five rationales of human spaceflight as “human destiny,” where it is a “logical step in human exploration,” or Michael Griffin’s “Real reasons… involve curiosity” (Launius, 2006; Griffin, 2007). Pursuing the unknown is in humanity’s inherent interest. Hence, human space exploration and space science experiments could be performed through international cooperation to satisfy ubiquitous desires.

Here is an example of potential international cooperation in science experiments. US space science experiments, for instance, could be conducted in the future Chinese space station. The current International Space Station (ISS) could be terminated after the Chinese station became fully operational. If US could end operations of the ISS, its annual operation cost of $3–4 billion could be eliminated (NASA Office of Audits, 2014).

Today, there are several bodies designed to promote and aid the feasibility of such international cooperation development. For example, the International Space Exploration Coordination Group (ISECG), a voluntary and non-binding coordination forum at the agency level, is studying human Moon and Mars exploration through international cooperation, while an intergovernmental Group on Earth Observations (GEO) is attempting to integrate Earth observation data to tackle global issues. The US could use these existing international communities to take a leading role to create integrated programs. US efforts to explore space could be a rationale on the surface, but the actual intention could be the cost sharing of US space programs.

Education

Education is the base of science and technology development, which is an indispensable element to achieve national economic growth (Neal, Smith, & McCormick, 2011). The US national approach in education is outlined in the National Science and Technology Council’s (NSTC) Federal Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) Education 5-Year Strategic Plan. NASA’s roles include that of supporting STEM education (NASA Act 2016). The NSTC plan indicates strong collaboration among schools, universities, research agencies, businesses, and communities is necessary to improve American STEM education. However, neither the NASA Act nor the NSTC plan refer to how the US could promote STEM education under international cooperation.

This does not suggest that the US education policy is pursued independently. The National Research Council’s (NRC) report urges that the US should promote global exchange in education and R&D talent: “US discourages or simply prevents the emigration of top talent. With more than 95 percent of the world’s talent residing outside the United States, recruiting internationally is essential, and will remain so even if our domestic compulsory education system becomes enviable.” (NRC, 2010, p.93) Unfortunately, there isn’t a clear way to reduce US space expenses for education by fostering international cooperation. Further research is required.

International Relations/Rule Making

The third potential Area of cooperation is International Relations/Rule Making. A global perspective on space was first addressed in the Outer Space Treaty (UN COPUOS, 1967). Since then, the governing of space exploration and the use of space have been sought internationally. This tendency gained more attention when, for instance, the Soviet’s nuclear-powered surveillance satellite Cosmos 954 crashed in Canada in 1978 (Health Canada, 2008), or the Chinese anti-satellite test in January 2007 that generated a large amount space debris, which fostered international community to protect long-term space sustainability (Gibbs, 2012). Commercial space activities further push the global community to create appropriate global rules to protect the competitiveness of space (Edythe, 2012).

Since the US has been a prime investor in space activities, the US should sustain its leadership in making rules to control free and peaceful use of space. Rules, including but not limited to protection of the space environment, sharing of space-derived information, global environment observation and disaster protection, and non-proliferation of space technology and export control are necessary. The UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) could be an appropriate place for the US to address these issues. As in the past, the US should continue proposing agendas to COPUOS and take initiatives in building a peaceful space environment.

| Although the international community may not be able to create concrete space rules, the US could take a leadership by making domestic space rules which serve as precedents for other countries. |

However, it is becoming increasingly difficult to create legally binding international rules. For example, a recent movement to create a binding international rule to mitigate space debris is proving difficult as it tends to be challenging to settle on an enforcement mechanism (Carns, 2017). Making a rule for non-proliferation of military technologies is another challenging field. In short, building valid international rules are politically less feasible. Thus, countries are now seeking more feasible, near-term, and pragmatic actions, such as transparency and confidence-building measure (TCBMs). A TCBM is not an approach to regulate space activities. Rather it calls on the international community to increase lucidity in space activities.

Whether through binding rules or TCBMs, the US would be the most powerful nation for any effort to create a peaceful space environment because the country’s domestic regulations for space activities have been often used for structuring space norms (Edythe, 2012). Therefore, although the international community may not be able to create concrete space rules, the US could take a leadership by making domestic space rules which serve as precedents for other countries.

After international rules and/or TCBMs are successfully developed, obtaining capabilities to monitor space activities becomes indispensable. This is where the US could reduce cost by sharing expenses with partners. Each country could incur costs to develop, operate, and maintain such space applications.

Combining competitive and cooperation strategies

Two Areas could be categorized under both competitive and cooperative approaches: Prestige/Leadership and Security and Defense.

Prestige/Leadership

Prestige and leadership is an area that can be pursued both independently and through international cooperation. The Space Race emerged when US national prestige was degraded by Sputnik in 1957 (McDougall, 1987). The consequences of that Space Race tell us that space technology is an effective tool to appeal to an advanced society and revive national prestige. However, an Apollo-like crash program to improve national prestige and leadership would not be necessary until the next political crisis occurs. Rather, space is deemed to be an effective tool to elaborate international prestige and leadership.

Both NASA and the Obama Administration expected to use outer space in order to realize international prestige and leadership through global partnerships (NASA, 2003; Obama, 2010). International cooperation would provide opportunities for the US to earn applause from international community with appealing advanced science and technology projects. For instance, the recently completed Cassini mission to Saturn, a joint program with NASA, ESA, and the Italian space agency, verified US advanced technologies. Cost-sharing based on function of individual organization was incorporated in this mission.

Security and Defense

Security and the defensive purposes of space is also an area where both competitive and cooperation approaches could be pursued. Space assets are amplifiers of the warfighter. Space systems enhance land, air, and sea forces through satellite communication systems; positioning, navigation, and timing; intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance systems; integrated tactical warning and attack assessment; and environmental monitoring (Hays, 2009). As can be inferred from the chart possessing these capabilities are vital for a sovereign country’s existence, thus, the US should maintain the competitive outlook. On the other hand, US cannot dismiss foreign countries’ security concerns, too: for example. a security concern of South Korea often becomes a security issue of the US, too.

Security issues outside US territory is often regarded as key US national security concerns; the National Security Strategy of 2006 addresses that “the survival of liberty at home increasingly depends on the success of liberty abroad.” (Bush, 2006, p.3). Space is thus used for the reconnaissance of regions far outside the US territory. These satellites’ development, maintenance, and operation could be managed by international cooperation since allies are also benefiting from these technologies. Hence, for the US, international cooperation is considered as a crucial strategy to sustain space capabilities: “With our allies, we will explore the development of combined space doctrine with principles, goals, and objectives that, in particular, endorse and enable the collaborative sharing of space capabilities in crisis and conflict” (DOD&IC, 2011, p.9). US intention toward international cooperation is thus clear.

The US-Japan security cooperation for space information sharing demonstrates a potential cost reduction approach. In April 2015, the Guidelines for Japan-US Defense Cooperation (Guidelines) were revised to enhance the Japan-US alliance. With regard to the space domain, the Guidelines emphasized the use of space for defense purposes and ballistic missile defense of the region (Chanlett-Avery & Rinehart, 2016). The Guidelines further addressed the effective cooperation in military space, stating, “the two governments will ensure the resiliency of their space systems and enhance space situational awareness cooperation” (MOD, 2015, p.21). These include gathering and sharing of intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance; logistics support; and training, among other araes. Therefore, improvement of the Japanese military space capability corresponds to an increase in the US regional security capability. Understanding this interdependency in military space between the US and Japan would help us find an approach to reduce cost. The following illustrates possible cost reductions from US-Japan military cooperation.

| Strong leadership would provide more opportunities for the US to develop collaborative space programs with foreign partners, which will help reduce US space spending. |

A report from the Center for Strategic and International Studies (2003) suggest that if the US could help Japan to improve an more economically efficient launch vehicle, then, Japan could also develop more valuable military space programs that contributes to regional security. The US could also reduce overall space data analysis expense by training less experienced Japanese analysts and share the US analysts’ workload. Japan’s own regional navigational satellite system, the Quasi-Zenith Satellite System (QZSS), could supplement US Global Positioning System. Moreover, QZSS would be a backup for the US military capability in East Asia region if the US space system became unavailable (Suzuki, 2017). This cooperation and mutual assistance would have a cost reduction effect in both development of hardware and in operations.

As these examples indicate, international cooperation in regional security has the potential to reduce US military space expenses, including space infrastructure and operation costs. However, since much of the information is not available to the public, further study is required on cost reduction pertaining to military space cooperation.

Conclusion

The 2010 National Space Policy addresses US leadership roles of creating peaceful space environment. The US should become, or continue to be dominant, in both competitive and cooperative programs to acquire and appeal overwhelming power among countries. Strong leadership would provide more opportunities for the US to develop collaborative space programs with foreign partners, which will help reduce US space spending.

References

Bardach, E. (2012). A Practical Guide for Policy Analysis: The Eightfold Path to More Effective Problem Solving (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Bush, G.W. (2004). President Bush Announces New Vision for Space Exploration Program. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

Bush, G.W. (2006). The National Security Strategy of the United States of America. Retrieved on October 14, 2017.

Carns, M.G. (2017). Consent not required: Making the Case that Consent is not Required Under Customary International Law for Removal of Outer Space Debris Smaller than 10CM2. The Air Force Law Review, Maxwell AFB77, 173-233.

Center for Strategic and International Studies. (2003). U.S.-Japan Space Policy: A Framework for 21st Century Cooperation. Washington, DC. Retrieved on October 14, 2017.

Chanlett-Avery, E. & Rinehart, E.I. (2016). The U.S.-Japan-Alliance (7-5700, RL33740), CRS Report: Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress. Congressional Research Service. Retrieved on October 16, 2017.

Coicaud, J.M. and Wheeler, J.N. (eds.) (2008). National interest and international solidarity: particular and universal ethics in international life. New York, NY: United Nations University Press.

Congressional Budget Office (1994). Reinventing NASA. Congress of the United States Congressional Budget Office.

Department of Defense and Office of the Director of National Intelligence (2011). National Security Space Strategy. Retrieved on October 16, 2017.

European Space Agency (2007). Resolution on the European Space Policy: ESA Director General’s Proposal for the European Space Policy (ESA BR-269). Retrieved on October 12th 2017.

Gibbs, G. (2012). An Analysis of the Space Policies of the Major Space Faring Nations and Selected Emerging Space Faring Nations. Annals of Air and Space Law, 37, 279-332.

Griffin, M. (2007). Proceedings from Quasar Award Dinner Bay Area Houston Economic Partnership on January 19, 2007: Space Exploration: Real Reasons and Acceptable Reasons. Houston, TX: National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

Handberg, R. (2002). Rationales of the Space Program. In: Sadeh E. (eds) Space Politics and Policy. Space Regulations Library Series,2, Springer, Dordrecht.

Harrison, T. & Cooper, Z. (2016). Next Steps for Japan-U.S. Cooperation in Space. Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Hays, P., (2009). Space and Military. Edited by C. Damon, P.T. Frances, Space and Defense Policy. Rutledge.

Health Canada (June 24th, 2008). The COSMOS 954 Accident,. Retrieved on October 14, 2017.

Hertzfeld, H. (1992). Measuring the Returns to Space Research and Development. In Greenberg, J. and Hertzfeld, H. (Eds.), Space Economics (151-169). Washington, D.C.: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics.

Hertzfeld, H. (2007). Commercial space and superpower in the USA. Space Policy, 23, 210-220.

Logsdon, J. (2005). Which Direction in Space?. Space Policy, 21, 85-88.

Logsdon, J. (2010). John F. Kennedy and the Race to the Moon. Palgrave Macmillan.

Mathematica, Inc. (1976). Quantifying the benefits to the National economy from secondary applications of NASA technology. National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

McDougall, W. A. (1997). The Heavens and the Earth: A Political History of the Space Age. Baltimore, MD: The John Hopkins University Press.

Ministry of Defense. (2015). The Guidelines for Japan-U.S. Defense Cooperation. Retrieved on October 14, 2017.

NASA (December 19th, 2003). Briefing for the President: Future U.S. Space Exploration: Alternative Visions, Key Elements, and Issues for Decision (unpublished presentation provided for President G. W. Bush). National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

NASA Office of Inspector. (2014) Extending the Operational Life of the International Space Station Until 2024 (IG-14-031, A-13-021-00). Audit Report, September 18, 2014, Office of Audits. Retrieved on October 16, 2017.

Neal, H. A., Smith, T. L., and McCormick, J. B. (2011), Beyond Sputnik: U.S. Science Policy in the Twenty-First Century. University of Michigan press.

Obama, B. (2010). Remarks by the President on Space Exploration in the 21st Century. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

Obama, B. (2010). NATIONAL SPACE POLICY of the UNITED STATES of AMERICA. Retrieved October 12th 2017.

OECD. (2014). The Space Economy at a Glance 2014, OECD Publishing. Retrieved on October 16, 2017.

Pollpeter, K. (2015). China Dream, Space Dream: China’s Progress in Space Technologies and Implications for the United States. Retrieved on October 12th 2017.

Roscosmos (2005). Russian Federal Space Program for 2006 – 2015 (No. 635). Government of Russian Federation.

Roscosmos (2012). Strategy of development of space activities in Russia until 2030 and beyond. Retrieved on April 29th 2012.

Samson, V. (2011). India, China, and the United States in Space: Partners, Competitors, Combatants? A Perspective from the United States. India Review, 10:4, 422-439.

Special Report on Innovation in Emerging Markets. (April 17th, 2010). The World Turned Upside Down. The Economist. Retrieved on October 14, 2017.

State Council (2016). Full text of white paper on China’s space activities in 2016. The State Council, The People’s Republic of China. Retrieved on October 12th 2017.

Suzuki, K. (2013). The contest for leadership in East Asia: Japanese and Chinese approaches to outer space. Space Policy, 29, 99-106.

Suzuki, K. (2017, October 10). Satellite Gives Japan Global Edge. The Wall Street Journal, p.A8.

The Space Foundation (August 3rd, 2017). Space Foundation Report Reveals Global Space Economy at $329 Billion in 2016. Retrieved on October 16, 2017.

United Nations COPUOS (1967). Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies (18 UST 2410, 610 UNTS 205, 6 ILM 386). Retrieved on October 14, 2017.

Vedda, V. (2009). Choice, Not Fate: Shaping a Sustainable Future in the Space Age. USA: Xlibris Corporation.

Weeks, E. (2012). Outer space development, international relations and space law: a method for elucidating seeds. Newcastle, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.