Eyes no longer on the prizeby Jeff Foust

|

| “This literal ‘moonshot’ is hard, and while we did expect a winner by now, due to the difficulties of fundraising, technical and regulatory challenges, the grand prize” will go unclaimed, Diamandis and Shingles wrote. |

It was intended to help begin a new phase of commercial spaceflight. “The Google Lunar X Prize is designed to kickstart Moon 2.0, a revolution in space to benefit all humanity,” said the narrator of a video played at the announcement event in Los Angeles, part of the Wired NextFest technology festival.

“We wanted an achievable first level, we wanted it to be doable by a small team,” said foundation chairman Peter Diamandis, who was joined at the event by Google co-founder Larry Page and Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin, among other luminaries (see “Google’s moonshot,” The Space Review, September 17, 2007).

More than ten years later, the prize ended with an electronic whimper. In a statement emailed by the foundation and posted on its website Tuesday, the organization announced that—to no one’s surprise, really—that the prize will expire in March without any team even launching a mission there.

“This literal ‘moonshot’ is hard, and while we did expect a winner by now, due to the difficulties of fundraising, technical and regulatory challenges, the grand prize of the $30M Google Lunar XPRIZE will go unclaimed,” said the statement, signed by Diamandis and Marcus Shingles, CEO of the X Prize Foundation.

After several extensions, the competition announced last year a final deadline: teams had to complete their missions by March 31, 2018. (The deadline previously required a launch by the end of 2017, but the foundation removed that requirement later last year, while maintaining the end-of-mission deadline of March 2018.) As last year progressed, though, it was increasingly clear that none of the five finalist teams—Moon Express, SpaceIL, Synergy Moon, Team Hakuto, and TeamIndus—would be ready to fly in time.

There was a flurry of activity towards the end of last year, as both SpaceIL and Team Hakuto made last-minute fundraising efforts to raise the money needed to build and launch their spacecraft. But even then, the teams were pessimistic that they would be ready to fly in time to meet the prize deadline.

“It is extremely challenging to make the end of March,” said Eran Privman, CEO of SpaceIL, in an interview last month when the team was seeking to raise $7.5 million. “We could take the spacecraft we just finished assembling, put it on the launcher, and launch by the end of March, but it wouldn’t be professional.”

“An extension of something like three to six months would be very helpful,” he said then. “We hope the management of the competition will be reasonable enough to understand that there are teams who are already close to launch.”

| “We held out an expectation or a hope that, if we all got together and had a chat with them, maybe there is a possibility, but that has not worked out,” said Narayan. |

Privman wasn’t alone in seeking an extension. Rahul Narayan, founder of TeamIndus, said in an interview last week that in order to complete their mission by the end of March, the team needed to launch its lander on an Indian Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV) by early March. Late last year, he said it clear they would not be ready in time to meet that launch deadline.

Narayan said he and other teams went to the X Prize Foundation and Google and sought yet another extension. “We held out an expectation or a hope that, if we all got together and had a chat with them, maybe there is a possibility, but that has not worked out,” he said.

Chanda Gonzales Mowrer, the X Prize Foundation official running the Google Lunar X Prize, suggested it was Google that had the final word on extending the prize, and decided not to. “A collective decision was made last year that there would be no more extensions and we have been very open with the public and with our teams that the end date for the competition would be March 31, 2018,” she said in a statement. “This being said, we appreciate Google’s commitment and respect their decision to have the prize purse expire on March 31, 2018, regardless of the progress we are seeing across the teams.”

A Google spokesperson declined to offer details about the company’s decision not to back another extension. “Though the prize is coming to an end, we continue to hold a deep admiration for all Google Lunar XPrize teams, and we will be rooting for them as they continue their pursuit of the Moon and beyond.”

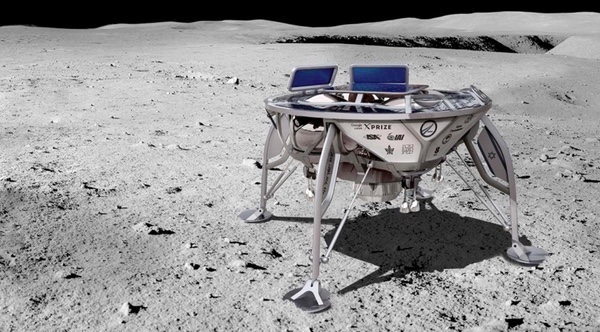

An illustration of Moon Express’ first lander, the MX-1E. The company is still planning to launch that mission, perhaps late this year or in 2019, as part of a series of lunar lander missions. (credit: Moon Express) |

The future of the teams, and of prizes

The X Prize Foundation did leave the door open to continuing the competition in some form, even without a cash prize purse. “This may include finding a new title sponsor to provide a prize purse following in the footsteps of Google’s generosity, or continuing the Lunar XPRIZE as a non-cash competition where we will follow and promote the teams and help celebrate their achievements,” Diamandis and Shingles said in their statement.

The teams plan on continuing development of their lunar landers regardless of the prize’s future, although with potential changes in their designs and schedules. Narayan said it has cancelled its PSLV launch contract with Antrix, the commercial arm of the Indian Space Research Organisation, but will continue work on its lunar lander for a future launch, possibly on another PSLV.

“We believe there is growing interest in doing science and delivering payloads to the Moon. As an aerospace startup, we see ourselves being part of that industry,” he said. “Over the next three to five years, we’re looking to launch to the Moon multiple times.”

| “We started the company to build a great business, not to simply win the prize” said Jain. “Winning the prize would have been just fine, too, because it’s icing on the cake, and who doesn’t love icing?” |

Technical work on that initial lander built for the X Prize is 80 to 85 percent complete, Narayan said, but was only “50 to 60 percent complete when it comes to the fundraising journey.” He said it’s unlikely they’ll make major changes to the lander now the prize is over, but could make some minor adjustments, such as adding payloads to the lander’s rover and reducing its range now that it no longer needs to travel 500 meters, a prize requirement.

He added TeamIndus’ partnerships with those flying payloads on the lander will be retained. That includes Team Hakuto, who had previously agreed to fly its rover on the TeamIndus lander.

Team Hakuto is a project of Japanese space startup ispace, which raised $90 million in Series A funding in December. That funding, company officials said, will be used for its own lunar missions: an orbiter planned for launch in late 2019 and a lander a year later.

“We wanted to make sure that our financing for the next two missions was in place,” Takeshi Hakamada, founder and CEO of ispace, said in an interview last month. “Through these two missions, we’re going to validate our technology to land on the Moon safely. After we validate the technology, we’re going to enter the lunar transportation business.”

Like TeamIndus’ Narayan, Hakamada said he sees a steady demand for lunar missions from companies and space agencies. “We are going to establish a transportation business to the Moon,” he said. “One key concept is regular, scheduled transportation to the Moon.” Such missions, he added, could fly as frequently as every month depending on customer demand.

Moon Express is also staying focused on its long-term lunar mission plans. The company had been quietly deemphasizing the prize last year, promoting instead a series of missions using its MX series of lunar landers that ranged from landing a telescope to performing a sample return mission.

A day after the X Prize Foundation announced the end of the competition, Moon Express chairman Naveen Jain noted it was unfortunate that the prize has ended. “Disappointment is certainly there,” he said in a speech webcast to the audience at the Space Tech Summit in San Mateo, California. He echoed the comments by the foundation that someone else might pick up sponsorship of the competition and its prize purse, although no companies have so far publicly stepped forward offering to do so.

“From our perspective, it doesn’t really matter that much,” he added, “because we started Moon Express fundamentally because it’s a good business, and that does not change.” Moon Express may still launch its first lander mission later this year, he said, “and if it goes to next year, so be it. We’re so close to making it happen.”

“With or without the prize, I think we’re going to be just fine,” he said. “We started the company to build a great business, not to simply win the prize. Winning the prize would have been just fine, too, because it’s icing on the cake, and who doesn’t love icing?”

SpaceIL had indicated that it planned to carry out its mission regardless of the prize, seeing it as an opportunity to inspire Israeli youth and encourage them to pursue science and engineering careers. While the team initially said its deadline for raising the money was the end of Hanukkah, and then the end of last year, it has not provided an update on its progress raising the $7.5 million.

“SpaceIL is committed to landing the first Israeli spacecraft on the Moon, regardless of the terms or status of the Lunar X Prize. We are at the height of our efforts to raise the funds for this project and to prepare for launch,” spokesman Ryan Greiss said in a statement after the X Prize Foundation announced the end of the competition.

Then there is the most quixotic of the five finalists, Synergy Moon, an international venture that incorporated several of the competition’s teams that failed to make the cut a year ago. The team has provided few details about its lander, and plans to launch it on an Interorbital Systems’ Neptune rocket, a vehicle that has yet to make its first flight.

Those obstacles, and the end of the prize, have not stopped Synergy Moon from continuing its efforts. “Synergy Moon is still sending a mission to the moon this year,” team leader Kevin Myrick said, adding more details would be forthcoming next week.

| “In conclusion, it’s incredibly difficult to land on the Moon,” Diamandis and Shingles said in their statement (emphasis in original). “If every XPRIZE competition we launch has a winner, we are not being audacious enough” |

The team also issued a press release stating that it was creating a new “space coalition” called Being in Synergy intended “to bring awareness and access to private space exploration, travel, technology and education to a broader audience.” The statement added that the team will make a “decisive announcement” about its lunar plans on April 12, the 57th anniversary of Yuri Gagarin’s launch.

And what of prizes themselves? When the X Prize Foundation announced the Google Lunar X Prize more than ten years ago, prizes were at perhaps the peak of their influence. It was less than three years since Scaled Composites won the Ansari X Prize, opening the door for a new era in commercial suborbital human spaceflight. NASA had caught prize fever as well, setting up a series of competitions under its Centennial Challenges program.

Today, prizes have lost some of their luster. Besides the failure of the Google Lunar X Prize, the suborbital spaceflight industry has not advanced as fast as expected in the years after the Ansari X Prize. There still hasn’t been a crewed suborbital commercial spaceflight since SpaceShipOne’s final prize-winning flight in October 2004, although both Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic appear to be finally inching closer to such flights this year, or next (see “2018 may (almost) be the year for commercial human suborbital spaceflight”, The Space Review, January 2, 2018). NASA’s Centennial Challenges program also continues, but at a low level.

Diamandis and Shingles, in their statement announcing the end of the competition, tried to play up what it produced over the last decade, from more than $300 million in investment and other revenue for the teams to milestone prizes totaling more than $6 million that the competition awarded in recent years as incentives to the teams.

The foundation also claimed it changed perceptions about commercial lunar missions. “Many now believe it’s no longer the sole purview of a few government agencies, but now may be achieved by small teams of entrepreneurs, engineers, and innovators from around the world,” they wrote of lunar missions. Of course, there were commercial lunar ventures prior to the prize, from LunaCorp and Applied Space Resources to Diamandis’ own Blastoff, all of which failed to blast off.

But at the prize ends, there is a renewed interest in lunar missions, thanks in part to changes in US space exploration policy. The Trump Administration’s fiscal year 2019 budget request, due to be released February 12, is expected to include programs to implement Space Policy Directive 1 (see “Where, but not how or when,” The Space Review, December 18, 2017). That will likely include opportunities for commercial ventures like X Prize teams; former competitors, such as Astrobotic; and other companies with lunar lander concepts, like Masten Space Systems and Blue Origin.

Depending on how that initiative develops, and who participates, the Google Lunar X Prize might yet have some influence on the future of space exploration and commercial space development. It may be years, though, before it’s clear what influence, if any, the prize really had.

“In conclusion, it’s incredibly difficult to land on the Moon,” Diamandis and Shingles said in their statement (emphasis in original). “If every XPRIZE competition we launch has a winner, we are not being audacious enough, and we will continue to launch competitions that are literal or figurative moonshots, pushing the boundaries of what’s possible.” The literal moonshots, though, will have to wait a while longer.