Equitable sharing of benefits of space resourcesby Vidvuds Beldavs

|

| Achieving a new consensus on outer space resources could be even more difficult now, in a time of increasing distrust and fragmentation internationally. |

The Moon Treaty was negotiated under the leadership of the United States. The US introduced the concept of the Common Heritage of Mankind into the draft of the Treaty in 1972 during the Nixon Administration.1 It is not an initiative of the Carter Administration. The US position remained unchanged over the decade until the draft was unanimously approved by COPUOS and subsequently unanimously approved by the General Assembly of the UN in 1979.

COPUOS reaches decisions by consensus among all member states. As a result, decisions can take longer than by majority vote. Consensus on policy governing the use of outer space resources was a remarkable achievement at the peak of the Cold War, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and the Iranian Revolution. In that era, memories of colonial exploitation were still fresh among leaders of developing countries. Neil Hosenbal deserves recognition for a historically significant achievement. The unanimous approval of the Moon Treaty could not have been achieved without him.

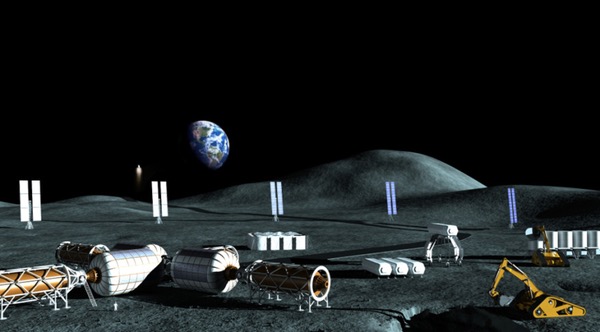

Achieving a new consensus on outer space resources could be even more difficult now, in a time of increasing distrust and fragmentation internationally. It is notable that recently the Russian Foreign Ministry signaled opposition to US and Luxembourg space law that permits appropriation of outer space resources. According to a December 1, 2017, article in Izvestia, Russia intends to mount a challenge in the upcoming session of the Legal Subcommittee of COPUOS April 9–20, 2018.2 An international consensus on general principles of outer space resource polity may, however, be necessary to enable developments like Moon Village and eventual settlements on Mars. Consensus on space resource policy could open the Moon and asteroids to peaceful use and potentially prevent war in space. However, the decade long saga of negotiating a Code of Conduct for outer space activities3 does not bode well for developing policy ex nihilo rather than building on the consensus achieved in COPUOS on the Moon Treaty during the 1970s. Can a Neil Hosenbal be found or emerge in our era who could guide the formulation of a consensus on space resource policy in the absence of a process and forum recognized by key spacefaring parties?

Common Heritage of Mankind

Central to criticisms of the Moon Treaty is the inclusion of the concept of the “Common Heritage of Mankind” (CHM) in the language of the Treaty and the call for the negotiation of an “international regime” to govern the exploitation of the natural resources of the Moon. The mining industry, whose interests were served by lobbyist Leigh Ratiner, had little concern about outer space resources in the late 1970s. Their primary interest was the Law of the Sea (LOS) Treaty then being negotiated. Ratiner saw no problem with CHM for outer space resources, if the CHM concept in the Moon Treaty were defined distinct from its usage in LOS in a protocol. During the 1980 Senate hearing, many organizations supported the position articulated by highly regarded space policy expert Eilene Galloway, who argued that it was entirely possible for the future lunar resource conference called for in the Moon Treaty to develop a regime like INMARSAT rather than like LOS. Galloway suggested that the United States set up an advisory committee to immediately begin working toward that goal.4

Another concern often raised about the Moon Treaty is that it is a socialist scheme that denies property rights and by implication restricts free enterprise. The Moon Treaty imposes no further restrictions on property rights than already exist in Article II of Outer Space Treaty:

Outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means.

| An international regime does not imply a rigid dictatorship that denies the sovereign rights of the participants. |

The Moon Treaty does not impose a moratorium on the exploitation of lunar resources prior to the negotiation and acceptance the international regime. This position was made clear in the closing statement of Neil Hosenbal, the head of the American delegation, at the final session of COPUOS where the Committee unanimously approved the language of the draft treaty that was subsequently submitted to the General Assembly of the UN for its unanimous approval.5 Explicit language in Article 6, par. 2, makes it clear that States Parties can extract space resources without limit even in the absence of an international regime:

In carrying out scientific investigations and in furtherance of the provisions of this Agreement, the States Parties shall have the right to collect on and remove from the moon samples of its mineral and other substances. Such samples shall remain at the disposal of those States Parties which caused them to be collected and may be used by them for scientific purposes. States Parties shall have regard to the desirability of making a portion of such samples available to other interested States Parties and the international scientific community for scientific investigation. States Parties may in the course of scientific investigations also use mineral and other substances of the moon in quantities appropriate for the support of their missions. [emphasis added]

International regime

The term “international regime” is a neutral term simply reflecting agreement on rules to govern an activity involving multiple states. As an example, there is international agreement on air traffic rules. Such air traffic rules could be referred to as a regime for air traffic control. A regime can be established without formal agreement: a simple verbal agreement by people using river water for irrigation could be a regime. An international regime does not imply a rigid dictatorship that denies the sovereign rights of the participants. There are numerous examples of voluntary international regimes, including the Antarctica Treaty.

Article 11, par. 5 of the Moon Treaty calls for the establishment of an international regime:

States Parties to this Agreement hereby undertake to establish an international regime, including appropriate procedures, to govern the exploitation of the natural resources of the moon as such exploitation is about to become feasible.

Feasibility includes economic and technical feasibility. If there would be no customers and markets for lunar and other outer space resources, no rules would be needed to govern the extraction of resources other than safety rules affecting all states. Hosenbal, in his closing statement, saw the need for experimentation and some exploitation of lunar resources as necessary to establish feasibility. If economic feasibility could not be established, use of lunar resources could continue in support of space missions. An example could be mining of lunar water ice for fuel and radiation shielding for missions to Mars. If, however, industrial use of lunar resources becomes feasible with growing markets, then rules to govern resource use will become increasingly necessary.

An international regime could establish industrial use rights to a defined territory that could give a company exclusive rights to exploit resources in the territory on the Moon for a defined period. Much of the lunar surface is covered by lunar regolith, pulverized surface rocks pummeled by meteorites, the solar wind, and cosmic rays for billions of years. While deposits of high-value minerals such as rare earths or platinum group may be discovered, most of the Moon’s surface consists of less valuable materials where multiple parties would compete for control of the same territory. Rules for use rights to such territory are unlikely to involve competitive bids. The rule could be simply that a claim of a party to a defined territory would be honored if improvements are made. In cases where highly valuable resources are present in a defined area the rules would need to provide for a transparent, competitive bidding process.

In the early phases of lunar development, use rights could be granted at no cost, just a declared willingness to work to develop lunar resources. However, an international regime may also require evidence of performance to retain exclusive rights even in such simple cases. The possibility of requiring performance can be included among the rules of the international regime based on the principles presented in Article 11, par. 7. Evidence of performance was a feature of homestead grants to farmers in the 1862 Homestead Act.6

| After the period of lunar exploration and as industrial development of the Moon gets underway, the needs of private enterprise and industry will become increasingly important. The rules of the international regime will need to reflect the interests of potential investors to support lunar development, and not UN bureaucrats. |

If major investment is required, investors may require lengthy periods of use rights, possibly extending to 100 years or more. These and other options can be accommodated within the rules that comprise the international regime. It is also clear that formulation of the rules would need to be dynamic and include input from investors, industry, and other interested parties.

After the period of lunar exploration and as industrial development of the Moon gets underway, the needs of private enterprise and industry will become increasingly important. The rules of the international regime will need to reflect the interests of potential investors to support lunar development, and not UN bureaucrats. Such investors are likely to require that use rights can be transferred to protect their investment. For example, a startup may demonstrate its technology to process lunar regolith to produce semiconductors sufficient to interest other investors, but the startup may not have the capacity to commercialize the technology itself. Transfer of its use rights to lunar territory could enable the startup to sell its assets to a larger firm that could commercialize the technology.

Whether the Moon Treaty is ultimately ignored or accepted as governing the use of lunar resources, the principles of Article 11, par. 7 can be used to construct an international regime for lunar development. Such a regime would need to meet the requirements of commercial business as well as of governments that provide support for lunar development. Additionally, benefits need to be made possible for developing countries that may have little direct role in making lunar development possible, but that are part of humankind. Bear in mind that Article I of the Outer Space Treaty raises general obligations:

The exploration and use of outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, shall be carried out for the benefit and in the interests of all countries, irrespective of their degree of economic or scientific development, and shall be the province of all mankind. [emphasis added]

Key principles guiding the formulation of the rules for the International Regime to govern the use of outer space resources are identified in Article 11, par. 7: “The main purposes of the international regime to be established shall include:

| Principle | Significance for space economy |

|---|---|

| (a) The orderly and safe development of the natural resources of the moon; | Lunar development should follow good business practices, managing health and safety considerations and environmental risks. |

| (b) The rational management of those resources; | Resources need to be managed to assure long term development rather than to maximize short term gains that may leave resources unexploited. |

| (c) The expansion of opportunities in the use of those resources; | The exploitation of the resources needs to generate sufficient returns on investment to justify expansion whether through increased volume of use or in the range of products produced from the resource or markets served. Investor needs must be satisfied, and the design of the regime must foster expansion of opportunities. |

| (d) An equitable sharing by all States Parties in the benefits derived from those resources, whereby the interests and needs of the developing countries, as well as the efforts of those countries which have contributed either directly or indirectly to the exploration of the moon, shall be given special consideration.” | This clause is an attempt to address the obligations imposed by Article I of the Outer Space Treaty that exploration and use of outer space shall be carried out for the benefit and in the interests of all countries, irrespective of their degree of economic or scientific development. For benefits to be shared the benefits must first be created in a form that can be shared. Equitable sharing of benefits is a common principle in agreements. No one could justify inequitable sharing of benefits derived from outer space. |

Equitable sharing of benefits

To share benefits equitably they must first be created in a form that can be shared. Clearly to impose some kind of royalty on resources that are extracted from the Moon or other celestial bodies may never create a benefit of potential value to developing countries. There would be no logic to actually share lunar resources as claimed in the statement from Wikipedia on the Moon Treaty that “extracted resources must be shared with other countries.”7

The lunar resource that is attracting the most intense interest at this time is lunar water. Dr. George F. Sowers Jr., Professor of Space Resources at the Colorado School of Mines and formerly chief scientist for United Launch Alliance, stated in a September 2017 Congressional hearing that lunar water at $500 per kilogram FOB lunar surface would be a gamechanger,8 representing a huge potential savings compared with the roughly $5,000 per kilogram cost to launch water to low Earth orbit. Possibly, lunar water will be a gamechanger. However, the size of the market and the benefits for people on Earth appear to not warrant any effort to quantify benefits to developing countries.

Over the next two decades there could be several missions to Mars that could use lunar water. None are likely to be private ventures even if companies providing various services for such missions could make a profit selling services to the government. Such a benefit to the US, China, Russia, ESA or other publicly funded efforts would generate no quantifiable benefit of value to developing countries. There would be no basis for equitable sharing of benefits from such a resource.

| An alternative way to frame equitable sharing of benefits for all States Parties would be to include lunar/outer space resources as an additional UN Sustainable Development goal. |

“Developing country” has many definitions. Over the years, as global wealth has increased, the number of developing countries has decreased. The category of least developed country (LDC) has a precise definition, while the World Bank stopped using the term “developing country” to define the development state of countries in 2016.9 If UN Sustainable Development goals were to be met, the number of LDCs would decrease dramatically. Would that mean that the number of countries warranting special consideration per Article 11, par. 7 (d) would decrease accordingly?

An alternative way to frame equitable sharing of benefits for all States Parties would be to include lunar/outer space resources as an additional UN Sustainable Development goal. Formulated in this way, the international regime for lunar development could include this goal: “Lunar resources will be developed to meet the space exploration interests of spacefaring states and to address the development needs of LDCs.”

Meeting Development needs of LDCs.

LDCs have inadequate infrastructure, particularly electrical power. Space-based solar power (SBSP) has been advocated as a solution to the power needs of LDCs by Dr. A. P. J. Abdul Kalam, the late former president of India.10 If the international regime for lunar development included among its goals that lunar resources will be developed to meet the development needs of LDCs, then efforts could be directed towards production of solar cells from lunar regolith as well as structures for space power facilities in Earth orbit. John Mankins’ recent review of SBSP points to the potential for space-power to compete with alternative sources.11 In the long term, the use of lunar resources can potentially reduce the cost of SBSP even more, opening the possibility of low-cost, carbon-free electrical power available even in the most remote regions on Earth. Lunar resources for solar power has been analyzed intensely by NASA with continuing efforts12 as well as by non-NASA researchers such as Peter Schubert.13

LDCs are deeply impacted by natural disasters. An early application of SBSP could be for disaster relief. The SBSP could be designed to be able to target disaster zones with portable rectennas transported by air to the site, potentially positioned on aerostats hovering above cloud layers delivering power to points below via cables. Rapid response capability to deliver substantial electrical power to disaster zones could be beneficial to all countries but particularly beneficial to developing countries.

The benefits to LDCs could be very large from SBSP constructed using lunar resources. LDCs could be shareholders in utilities that manage the SBSP facilities. The consumers in developing countries would pay for the power. World Bank and other concessionary financing could be used to finance SBSP systems. Direct benefit to LDCs from lunar development could fulfill Article 7(d) of the Moon Treaty of equitable sharing of benefits from lunar resources without imposing additional costs on the space exploration programs of spacefaring countries. The Moon Treaty is flexible enough to accommodate such interpretations of sharing of the benefits of use of outer space resources.

Endnotes

- Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space verbatim record of 203d meeting Neil Hosenbal closing statement pages 21.

- See Izvestia article (in Russian).

- US-China Economic and Security Review Commission. “China’s Position on a Code of Conduct in Space” September 11, 2017.

- The sole objection to the Treaty for Ratiner and the mining industry was the inclusion of CHM. See “Moon Treaty Hearings”, L5 News, September 1980.

- Hosenbal, pP. 22.

- “What Is a Land Grant? (Part 2): Grants to Individuals for Homesteading and Settlement” Grants.gov, November 21, 2016.

- Wikipedia. “Moon Treaty: Ratification.”

- House Science Committee. “Testimony of Dr. George F. Sowers, Jr.” September 7, 2017. pg. 4.

- Wikipedia. “Developing country.”

- National Space Society. “Kalam-NSS Energy Initiative.” November 4, 2010.

- Mankins, J. 2017 “New Developments in Space Solar Power”

- NASA. “NASA Selects Economic Research Studies to Examine Investments in Space” September 13, 2017.

- Schubert, Peter. “Energy Resources Beyond Earth – SSP from ISRU” November 2014.