New vehicles, new companies, and new competition in the launch marketby Jeff Foust

|

| “We feel very confident about our schedule,” Bruno said of development of Vulcan. |

The introduction of the Falcon 9, with its low prices compared to those competitors, certainly changed the dynamics of the market. But today companies are still launching their satellites on the Ariane 5, Atlas V, H-2, and Proton, in addition to the Falcon 9. The Zenit-3SL has effectively been sidelined, but even there Sea Launch, transitioning to new ownership, is planning to revive the vehicle despite uncertain market prospects. The market has changed, but the vehicles, to first order, have not.

Five years from now, though, the situation may be very different. By the early to mid 2020s, the Ariane 5, Atlas V, and H-2 will all be retired, replaced by next-generation vehicles whose designs have been shaped by the cost pressures created by the Falcon 9. ILS is trying to find new niches for the Proton as its once-major share of the commercial market slips. And Blue Origin and SpaceX have new vehicles in the works that could further upend the market.

Vulcan: coming soon

The vehicle whose development has generated the most interest (outside of Blue Origin and SpaceX) is United Launch Alliance’s Vulcan. That vehicle is scheduled to make its first launch in a little more than two years: mid-2020, company officials have said recently.

“We feel very confident about our schedule,” company CEO and president Tory Bruno said in a roundtable with reporters March 13 during the Satellite 2018 conference in Washington.

That confidence comes even though ULA has yet to announce its choice for the engine for the rocket’s first stage: Blue Origin’s BE-4 or Aerojet Rocketdyne’s AR1. While BE-4 has long been considered the front-runner, ULA has not made a formal choice while BE-4 testing continues. Bruno has a one-word answer whenever someone asks when that selection will be made: “soon.”

Bruno acknowledges, though, that the BE-4 is a better fit to the company’s schedule for both that inaugural launch and plans to have the Vulcan certified by the US Air Force for national security missions in 2022. “The Blue Origin engine is further ahead in its development because it started first. The Aerojet Rocketdyne engine is not as far ahead because they started second,” he said.

The company’s timelines, he said, are consistent with selecting the BE-4. “If we were to select Aerojet Rocketdyne, that puts much more pressure on that” schedule, he said. “Our plan has a year to a year and a half margin. That would pretty much be consumed if we were to select AR1.”

| “I will not fly a car,” Bruno said of those initial Vulcan launches. “I guess if a customer wanted to pay me to fly a car I’d consider it. I will not fly my car. I like my car.” |

A number of factors go into the engine decision, Bruno said. They include technical aspects of the engine’s performance, the funding available for the engine’s development, schedule for the engine’s readiness, and the engine’s recurring price. “There are detailed criteria that we have been scoring each engine against as we move along,” he said. “It is the scoring against that that allows us to make an engine decision, which will happen soon.”

“Can you elaborate on ‘soon’?” a reporter asked.

“No.”

ULA is thinking ahead about marketing Vulcan, even with a key design aspect yet to be determined. The first two launches, Bruno said, will be commercial, although the company has yet to sign any contracts for it. Those initial commercial launches will satisfy certification requirements to allow Vulcan to also serve government customers.

“I will not fly a car,” he said of those initial Vulcan launches, a reference to the Tesla Roadster carried on the first Falcon Heavy launch in February. “I guess if a customer wanted to pay me to fly a car I’d consider it. I will not fly my car. I like my car.”

The company is paying increased attention to the commercial market as part of that effort. Earlier this year it announced it was taking marketing of the Atlas 5 in-house; that vehicle had been sold by Lockheed Martin Commercial Launch Services since the ULA merger took effect more than a decade ago.

“We can talk directly to those customers, which can make it easier to customize solutions for them,” he said, citing the large number of configurations based on the size of the payload fairing and number of strap-on boosters. “That’s very hard to do when we’re working through a third party. It’s much easier to do now.”

Bruno also said it would result in lower prices. “We should be able to offer them a better deal,” he said of potential customers. “We’re looking for the same kinds of margins. We’re not actually trying to do this to make higher profits. We’re trying to do this to be more competitive.”

Bruno, during a panel discussion the day before at Satellite 2018, said ULA was now able to focus more on the commercial market because of the success it achieved for its government customers. “Our job for the first decade was to help the United States avoid a serious crisis in space. The assets were aging out. The replacements were late. We were asked to be able to fly with perfect reliability because you couldn’t afford to lose any,” he said.

“That crisis is over. We helped solve it,” he said. “So now, we are able to shift our attention to the commercial marketplace, and we’re pretty excited to be able to do that.”

| “We don’t really have the luxury of some of my other colleagues up here as far as funding, so we’re very strategic about how we do our development,” said ILS’ Pysher. |

That doesn’t mean, though, that commercial will be the largest part of ULA’s customer base. Bruno estimated during the roundtable that the company would have the ability to launch up to 20 Vulcan rockets a year when in full production, and after the Atlas V is phased out in the early 2020s. (The “single-stick” version of the Delta IV is retiring this year, but the larger Delta IV Heavy may continue flying into the mid-2020s until replacement vehicles, including a heavier version of Vulcan, are certified.)

Of that projected future launch rate, Bruno estimated only about 20 to 30 percent will be commercial. “The majority, our core, will still be national security space and NASA science missions,” he said.

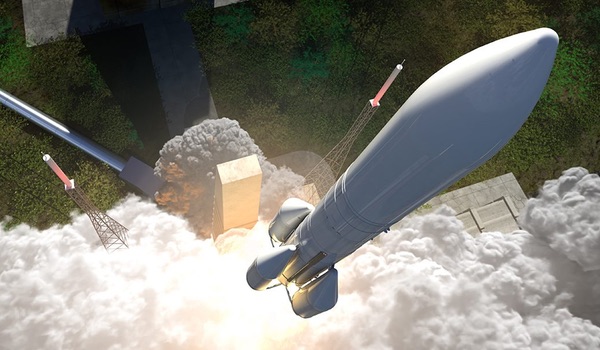

Ariane 6 is scheduled to make its first launch in 2020, with the Ariane 5 phasing out of service a few years later. (credit: Arianespace) |

New vehicles and new entrants

Vulcan, though, is not the only next-generation vehicle entering service in the next few years. Arianespace is developing the Ariane 6, whose development remains on schedule for a first flight around the same time as Vulcan in mid-2020.

“We’re targeting a maiden flight in the middle of 2020,” said Stéphane Israël, CEO of Arianespace, during the Satellite 2018 panel. “We are on track to do so.” Key tests of the vehicle’s engines are ongoing, he said, with a critical design review scheduled for this summer.

MHI has been developing a successor to the H-2, the H3, which is also scheduled to debut in 2020. Like the Ariane 6, it has a critical design review coming this year while tests of the rocket’s first stage engines continue, said Ko Ogasawara, vice president and general manager of space systems business development at MHI. “It’s completely on track,” he said during the panel session.

He added that, in addition to the development of the H3, MHI was building a second launch pad at the Tanegashima Space Center. With one launch pad currently available for the H-2, the vehicle’s launch rate is limited to about six per year given time needed to repair the pad between launches. With a second pad, he estimated the H3 could perform two launches in three weeks, and ten in a year.

ILS is in a different situation. Long-term plans have been to ultimately replace the Proton with the Angara rocket, a vehicle whose development predates not just other next-generation vehicles but even some of the companies in the industry, like Blue Origin and SpaceX. For now, the company is looking for ways to modify the Proton rocket to address changes in the market.

“We don’t really have the luxury of some of my other colleagues up here as far as funding, so we’re very strategic about how we do our development,” said Kirk Pysher, president of ILS. “Currently we’re investing in the factory to bring new technology into the quality systems to help eliminate some of the opportunities for human error.”

ILS has also been offering new, smaller versions of the Proton M. The Proton Medium is a two-stage version of the Proton intended for medium-sized GEO satellites as well as for LEO satellite constellations. “It suits very well with the LEO constellation programs,” he said. “The restartable Breeze-M upper stage allows us to insert into multiple planes. That vehicle is nearly at the sweet spot of where we believe the market is today.”

During the conference ILS announced “multiple launch assignments for Proton Medium launches” starting in late 2019. Absent from the announcement, though, was any mention of the customers, or the specific number of launches.

| “We spent so much time and effort getting these vehicles certified—certified for crew, certified for the US Air Force and the national security space community—we’re going to want to make sure we’re flying these vehicles as long as those customers need to fly them,” Shotwell said of Falcon 9 and Heavy. |

But as established companies work to develop new vehicles or revamp existing ones, new (or relatively new) entrants are still shaping the market. SpaceX, which introduced the Falcon Heavy last month, is planning to start launches using the new Block 5 version of the Falcon 9 in April. That vehicle, often called the “final” update to the Falcon 9, incorporates enhancements to improve the reusability of the first stage, allowing it to be reused ten or more times, versus the two to three flights of older versions of the rocket.

There’s also SpaceX’s next-generation vehicle, the BFR (formally designated as “Big Falcon Rocket” but with an alternative, cruder expansion) that is in development. At the Falcon Heavy launch last month, company CEO Elon Musk said “short hops” of the upper stage, or “spaceship,” part of BFR could begin next year, possibly at the company’s South Texas launch site under construction. Musk reiterated that timetable during an onstage interview at the South by Southwest festival in Austin, Texas, March 11.

When the BFR enters service—the early 2020s, if you concur with Musk’s admittedly “optimistic” schedules—it won’t mean the immediate end for existing vehicles. “There’ll be significant overlap from when the BFR is flying with the Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy,” said SpaceX president and COO Gwynne Shotwell at the Satellite 2018 panel. “We spent so much time and effort getting these vehicles certified—certified for crew, certified for the US Air Force and the national security space community—we’re going to want to make sure we’re flying these vehicles as long as those customers need to fly them.”

She offered her own ambitious schedule for BFR. “BFR will probably be orbital in 2020 or so,” she said. “We should see short hops starting next year, 2019.”

And Blue Origin is making progress on its own large orbital launch vehicle, New Glenn. With the factory for it now complete and the BE-4 engines it will use going through testing, the company expects to have a first launch for the vehicle, from a pad under construction at Cape Canaveral, by the end of 2020 (see “A changing shade of Blue”, The Space Review, March 19, 2018.)

A big selling point for the vehicle, company CEO Bob Smith said, was not just its payload mass capacity but also its large volume enabled by a payload fairing seven meters in diameter, a design change the company announced last fall. “Everybody wants more volume,” he said. “It’s received a tremendous reception in the marketplace.”

But that competition also creates conflicts. Blue Origin is offering ULA the BE-4 engine for Vulcan, yet Blue Origin’s New Glenn will compete against Vulcan for commercial launches and possibly national security missions as well, as Smith has previously suggested an interest in certifying New Glenn for government payloads.

Bruno, at the media roundtable, said he was not concerned. “It’s not an unusual thing in our industry to be in that situation,” he said. He cited as an example Orbital ATK, which is competing with ULA for the ongoing Launch Service Agreements program by the Air Force to certify vehicles like Vulcan and Orbital’s Next Generation Launcher. Orbital, he said, also is a supplier to ULA, providing solid rocket boosters for the Delta IV and soon Atlas and Vulcan. Orbital has also purchased Atlas launches of its Cygnus cargo spacecraft.

“That full circle is not all that rare, and we have ways of constructing our contracts and our relationships to allow us to feel comfortable with that,” he said, adding ULA would take a similar approach if it selected the BE-4 for Vulcan while competing against New Glenn.

That and other developments make for an interesting next few years for the industry, as venerable launch vehicles are retired and promising, if still unproven, vehicles take their place. “Six healthy launch companies. That’s pretty exciting,” Bruno said on the panel that he shared with Arianespace, Blue Origin, ILS, MHI, and SpaceX. How many of those companies can remain healthy, particularly given weak demand for GEO satellites and uncertain futures for LEO constellations, will be a key challenge for the next several years.