The Earth, space settlement, and the hard drive analogyby John K. Strickland

|

| Although Robinson strongly defends space science funding, he shows his skepticism that Mars settlement will begin any time soon. |

Robinson has long acknowledged his political views, but generally they do not interfere with his excellent storytelling. Much of the left has historically not been kind to or interested in space exploration, frequently considering it to be in effect a game played by rich white capitalists with expensive rockets as the toys. The article referenced a poem written in 1970 by Gil Scott-Heron that essentially argues for perfect economic equality before any space activity should be allowed, with the line “I can’t pay no doctor bill / but Whitey’s on the Moon.” Even the revered Carl Sagan, long hostile to human space exploration until his last years, would probably have objected to a private factory or mine on Mars, even if it were vital for creating a human settlement.

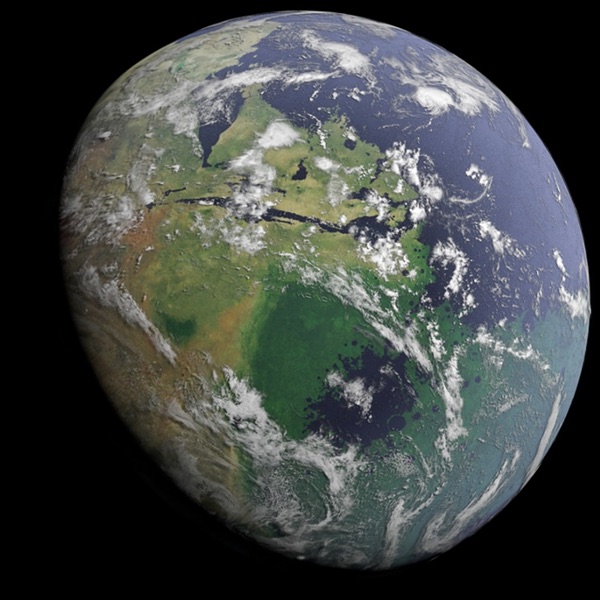

One of the common analogies used by space settlement supporters, including me, has been the “hard drive analogy.” It focuses on the concept of backing up a hard drive with years of data, text, and precious photos on it by making a copy of the whole drive or parts of it, and compares the idea of creating space settlements to making copies of the Earths biosphere, humanity, and all of its customs, knowledge, skills, and cultural and artistic records. We acknowledge that, for many people, it is a very large mental leap from a single hard drive backup to essentially backing up what most people consider everything that exists on Earth. (Many people have never backed up their hard drives and rely on good luck to protect them from data loss.) To most people, the universe around the Earth does not seem to be a significant part of their reality and since city lights make the stars hard to see, most people focus on the present, the Earth, and maybe just their immediate surroundings. For them, the universe beyond the Earth might as well not exist.

Although Robinson strongly defends space science funding, he shows his skepticism that Mars settlement will begin any time soon. He says:

Billionaires moving to space is not just similar to a sci-fi plot—it is a sci-fi plot, and not very realistic.

It has to be said: There is no Planet B. It’s here for us, or nowhere. But really, that is very obvious. Very few people actually believe that setting up a small settlement on Mars is an adequate safeguard or mitigation for the damage we are doing here on Earth. Those who do are fooling themselves.

Mars and all the rest of outer space are spectacularly unsuited as another basket to put our eggs in. The rich can always just move to Malibu or Davos and hire guards. That’s the outer space being referred to.

Astonishingly, Robinson here ignores the whole point of his famous trilogy, where humanity is able to modify its environment, eventually including entire planets, to enable its survival and ability to thrive and grow. He obviously does not realize that the problem of landing human-sized vehicles on Mars has been solved in principle (and demonstrated many times by the Falcon 9 rocket’s entry burn and landings) and envisions any attempts to create settlements as risky and doomed to fail and be forgotten. Notice that his negative focus is on the billionaire himself moving to Mars, not the settlers that Elon Musk envisions, who would need to work hard to make the settlement succeed. The space billionaires are actually the ones who are working to reduce the cost of access to space so that the ordinary person, not just government employees, can travel into it.

| Robinson also objects to the idea that capitalists like Elon Musk can get rich enough to do some of the things that government should be doing but refuses to do due to inertia, politics, a lack of imagination or corruption. |

People were living in the hostile environment of Siberia tens of thousands of years ago, and without the benefits of modern technology. Rapidly developing space technology is vastly more powerful than what those ancient Siberians had. For example, adding enough nitrogen and perfluorocarbon gases to the Martian atmosphere can make the planet livable again after being like an arctic desert in a near vacuum for about three billion years. Mars actually has plenty of water for human use, it is just all frozen solid. With enough air pressure, water would flow again and rain and snow would fall. Turning Mars into a living and warmer world would also allow backup biomes for much of Earth’s life forms, rather than just humans and their economically critical food and fiber species and pets. Fish and cetaceans could eventually thrive in at least one ocean, and birds could fly through Mars air.

Robinson also totally ignores the entire concept of people living inside rotating space settlements in Earth or solar orbit instead of on planetary surfaces, which are at the bottom of gravity wells. In 1974, Gerard K. O’Neill argued that such habitats might be superior to those on planetary surfaces. (Copies of hard drives can be made in more than one way.) Large numbers of such settlements can be made out of materials from asteroids and can eventually support huge numbers of people and biome refuges. Gravity and temperatures can be precisely maintained in such structures. So space settlements on planetary surfaces are not the only option. The development of new means of construction and fabrication in space will enable such huge structures to be built economically.

Robinson also objects to the idea that capitalists like Elon Musk can get rich enough to do some of the things that government should be doing but refuses to do due to inertia, politics, a lack of imagination or corruption. He asks, “Why are there people as rich as this anyway?” What is really going on now is that some of the billionaires have realized that governments are mired down, frequently unable to act, and somebody needs to be the point man. Some of them are ready to step up to the plate. If there were no billionaires, there would be no future point men to do what the government will never do.

Paradoxically, Robinson supports a vastly expanded NASA budget, spent almost entirely for space science. He extols the idea of Mars as a permanent scientific laboratory zone like Antarctica, but including no human settlements. He considers governments the only legitimate actors for large-scale projects. Like many of those on the left who hold science in awe, he also seems to believe that humanity should be the tool of science, whereas science is supposed to be a tool for humanity’s benefit.

| The Earth, the only known abode of life, is precious beyond measure. Why would space settlement advocates want to let its ability to support life be destroyed? Are not two copies better than one? |

Robinson continues with this attitude: “Very few people actually believe that setting up a small settlement on Mars is an adequate safeguard of mitigation for the damage we are doing here on Earth.” Here he is perpetuating the view of human space activities as a zero-sum game where a tiny number of space explorer heroes win and the Earth loses. In fact, many human activities end up as a win-win situation. A single, small, static, human settlement, permanently restricted to the underground, would not be very useful if it stays that way. Humans only thrive when their community is growing.

The anti-space settlement position relates to the left-wing attitude, similar to the old “Earth First” argument, that space settlement advocates do not value the Earth, but just want to abandon it to its fate and escape to a “space nirvana.” Thus, in their view all efforts in space, not just settlement, should be stopped until the entire Earth is an environmental paradise with all social ills, war, and political strife eliminated and where everyone is economically equal. This argument ignores the fact that if the Earth became uninhabitable for whatever reason, the main “hard drive repository of life” would have been lost. Space advocates are probably more aware of this than most people. Many are also strong backers of space solar power, which is the only known energy source that has the sheer capacity to replace existing fossil fuels without requiring massive amounts of mining and industrial activity.

The Earth, the only known abode of life, is precious beyond measure. Why would space settlement advocates want to let its ability to support life be destroyed? Are not two copies better than one? Settlement advocates consider the Earth and its biome so precious that they want to go to a stupendous effort to make a viable copy or copies of it. In no way would they stand by while the Earth itself was lost. If the ability to terraform a planet can be developed, and the Earth’s habitability were lost for any reason, that ability could be used to make the Earth habitable again and the backup settlements could act as seed reservoirs. In addition, space development would give humanity a much more powerful ability to protect the Earth from natural catastrophes such as asteroid impacts. One potential reason for the apparent lack of other civilizations is that Earth has been very lucky in not having more frequent extinction-level impacts. This suggests that having an active in-space asteroid defense system may be very important.

Here on the Earth’s surface, we are in effect at the bottom of a gravity well thousands of kilometers deep, where very large rocks (asteroids) can fall on our heads at any time, potentially obliterating all life at the bottom of our cozy pit. If we had a foothold on the vast gravitational plain that surrounds the Earth, we could prevent such calamities. The dinosaurs had no such protection and their world ended in a blaze of blinding light, terrifying tsunamis, and a literal global rain of fire, probably followed by an impact winter. To most space opponents, such threats do not seem real, but at least the news media now recognizes the danger after coverage of the Chelyabinsk meteor event in 2013 showed that such an event could be terrifying and catastrophically destructive.

To prevent humanity and most of the other millions of species alive on the Earth now from going extinct, we need to continue climbing out of our gravity well, developing and settling in many locations where it is practical and affordable. Eventually, we should be able to expand to settle locations in other star systems, bringing life itself to other parts of our galaxy. Much as the establishment of the New World settlements and eventually the United States (free of the restrictions and customs of the Old World) helped lead to the creation of true modern democracies and freedoms, independent human settlements off the Earth may also lead to undreamed-of human advances. Let’s celebrate and encourage the continuing human expansion into space and all that it offers humanity.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments subcommitted to deal with a surge in spam.