Keep dreaming, young lady, keep dreamingby Dwayne A. Day

|

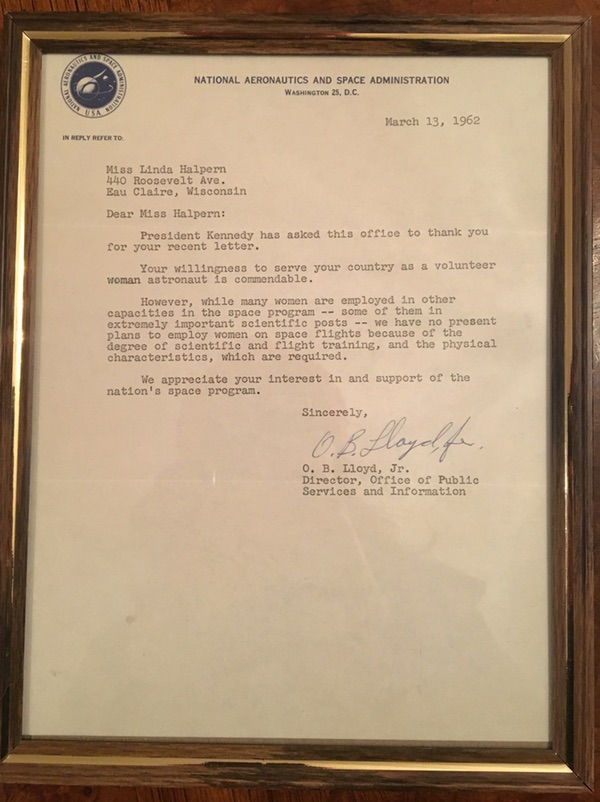

| In fact, February and March 1962 appear to have been a rather active time for discussion of the possibility of female astronauts—and efforts by government officials to squash such talk. |

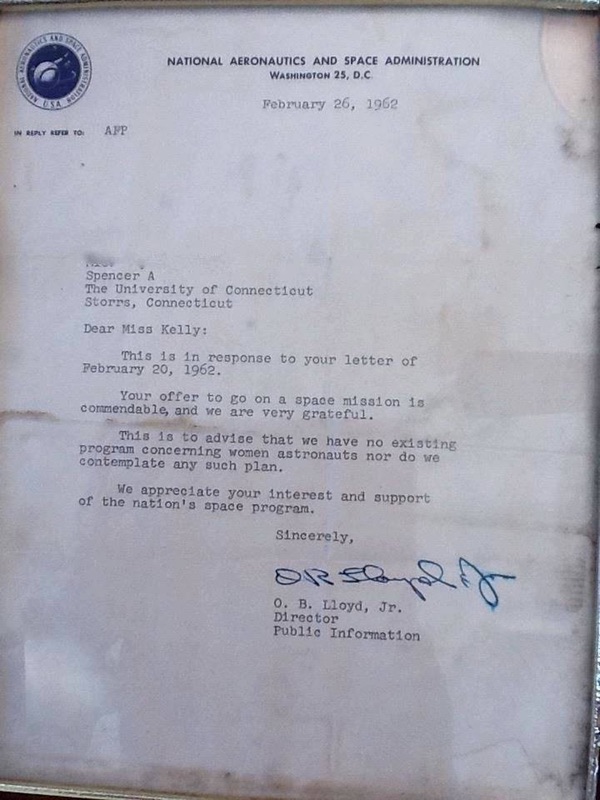

Crushing girls’ and women’s dreams of spaceflight appears to have been a regular task for Mr. Lloyd, because only a few weeks earlier he had written a similar letter to a female student at the University of Connecticut. That letter turned up on Reddit.com in January 2013 shared by somebody who claimed it had been sent by NASA to their friend’s mother in February 1962. The letter was apparently in response to a Ms. Kelly’s query about going on a space mission. “This is to advise that we have no existing program concerning women astronauts nor do we contemplate any such plan.”

|

The existence of two letters concerning the same subject written within weeks of each other implies that there may have been more. In fact, February and March 1962 appear to have been a rather active time for discussion of the possibility of female astronauts—and efforts by government officials to squash such talk. Jackie Cochran, Jerrie Cobb, and the other so-called “Mercury 13” women had been publicly speaking and agitating about the issue, and two of them were about to meet with Vice President Lyndon Johnson. Johnson’s assistant Liz Carpenter drafted a letter for Johnson that asked NASA administrator James Webb to look into it. The draft letter was dated March 15, 1962, and was discovered by historian Margaret Weitekamp in the LBJ Presidential Library (in 2016, Dr. Weitekamp wrote about the Halpern letter.) The letter was reprinted in her 2005 book Right Stuff, Wrong Sex and stated:

I have conferred with Mrs. Philip Hart and Miss Jerrie Cobb concerning their effort to get women utilized as astronauts. I’m sure you agree that sex should not be a reason for disqualifying a candidate for orbital flight.

Could you advise me whether NASA has disqualified anyone because of being a woman?

As I understand it, two principal requirements for orbital flight at this stage are: 1) that the individual be experienced at high speed military test flying; and 2) that the individual have an engineering background enabling him to take over controls in the event it became necessary.

Would you advise me whether there are any women who meet these qualifications?

If not, could you estimate for me the time when orbital flight will have become sufficiently safe that these two requirements are no longer necessary and a larger number of individuals may qualify?

I know we both are grateful for the desire to serve on the part of these women, and look forward to the time when they can.

Sincerely,

Lyndon B. Johnson

Johnson chose not to send the letter to NASA. Instead, in large script he wrote at the bottom “Lets stop this now! File.” Liz Carpenter duly filed the letter and it remained unknown for four decades, until Weitekamp unearthed it. Had NASA administrator Webb received a letter from the vice president, the agency probably would have responded differently than it already had to Ms. Halpern and Ms. Kelly and who knows how many other women who had been asking about when women astronauts might fly.

| There is a larger cultural history of women astronauts, and the aspirations of girls and young women who read about the Mercury program and watched missions on television and dreamed of flying in space themselves. Like cultural history in general, it is not easy to cover this topic because it was not always, or even often, recorded, but that is no reason that the subject should be ignored. |

What we have now are three letters, dated February 26, March 13, and March 15, 1962, the latter one never sent. That seems like more than a coincidence and probably the result of very active discussion—and lobbying—by women around the country. One possibility is that there was an active letter-writing campaign by young women to NASA to try to exert pressure on the agency to start accepting women astronauts. Perhaps there are more rejection letters written by Mr. Lloyd still waiting to be found, buried in archives or in dusty boxes in attics. What is almost certainly not a coincidence is that the letters all followed John Glenn’s February 20, 1962, orbital flight. Young women saw that flight and were inspired by Colonel Glenn.

By the early 1960s, NASA was receiving pressure from several directions to allow women to become astronauts, and had repeatedly refused, although up until summer 1962 agency officials had treated the issue as a minor annoyance that did not require high-level attention or formal policy declarations. Only a few months after these letters to NASA about women astronauts were written, in summer 1962, John Glenn—by then America’s hero—testified in front of Congress that there were no plans for women astronauts and that they were not necessary. He even joked that if women became astronauts, the men would welcome them “with open arms,” to the laughter of the men on the House Space Committee. Clearly, he did not consider it a serious subject. “I think this gets back to the way our social order is organized, really,” Glenn said. “It is just a fact. The men go off and fight the wars and fly the airplanes and come back and help design and build and test them. The fact that women are not in this field is a fact of our social order.”

Most of the historical literature about the possibility of women astronauts during the Mercury program has focused on the “Mercury 13.” In April Netflix premiered a new documentary about them and two docudramas on that subject are reputed to be in the works. But the subject of women astronauts during the Mercury program goes beyond that topic and deserves more attention. There is a larger cultural history of women astronauts, and the aspirations of girls and young women who read about the Mercury program and watched missions on television and dreamed of flying in space themselves. Like cultural history in general, it is not easy to cover this topic because it was not always, or even often, recorded, but that is no reason that the subject should be ignored. Rather, it is a challenge to enterprising historians.

|

Women astronauts in popular culture

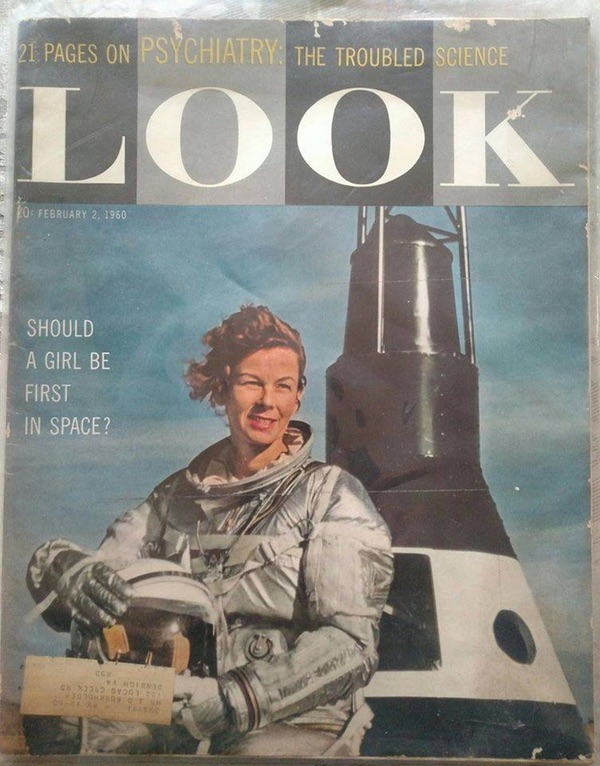

The subject of women astronauts must have seemed very real to young women at that time, because it was in the news and in the popular culture. The February 2, 1960, issue of Look magazine featured a woman in front of a Mercury mock-up and the heading “Should a girl be first in space?” The article itself took a rather pessimistic view, citing Brigadier General Don Flickinger, assistant for bio-astronautics of the Air Research and Development Command, who believed that women astronauts would not be considered until the United States had a semi-maneuverable spacecraft that could carry three people. The article suggested that the Soviet Union might have such a spacecraft by 1965. The article also noted that the Soviet Union, due to a manpower shortage, employed more women in technical roles than the United States. The obvious, although unstated implication was that the Soviets would launch a woman astronaut first—which of course they did, in June 1963.

The article also stated that “our first girl in space will probably be a flat-chested lightweight under 35 years of age and married. Though not an outstanding athlete, she will have extraordinarily precise co-ordination. She will be a pilot. Her interests will tend toward swimming and skiing, rather than a more muscular sport like wrestling. She will adjust well to isolation and be able to ‘hibernate,’ but also to snap into immediate alertness. Her personality will both soothe and stimulate others on her team.”

| Martin Caidin declared that “There’s no reason in the world why a woman wouldn’t do as well as a space ship crew member as a man.” But he went downhill from there. |

It continued: “Her first chance in space may be as the scientist-wife of a pilot-engineer. Her specialties will range from astronomy to zoology. She will not be bosomy because of the problems of designing pressure suits. She will not smoke or have a history of major surgery or mental disorder. Her menstruation will be eliminated by inhibiting medication. She will be willing to risk sterility from possible radiation exposure.”

The author claimed that this sketch of the first woman astronaut was based upon discussion with “doctors, generals, psychologists and engineers directly involved in our manned space programs.” They agreed that women would follow men into space. “Many believe that women’s biggest obstacle to being first is our cultural bias against exposing them to hazardous situations. That is why they cannot become military test pilots, the convenient category of healthy, skilled specialists from which our seven astronauts were chosen. Several authorities, in fact, privately question the use of the test-pilot category for the first manned test flights.”

There had been other discussions of women astronauts early in the space age. The March 1958 issue of Real (“The exciting magazine for men”) featured a lunar spaceship on the cover and the heading “You and space travel.” Inside was an article by Martin Caidin, who declared that “There’s no reason in the world why a woman wouldn’t do as well as a space ship crew member as a man.” But he went downhill from there, concluding that the primary reason to include women on spaceship crews was so that men could have sex with them. (The idea that the libidos of male astronauts would create problems was not unique to Mr. Caidin: A.E. van Vogt’s 1950 novel The Voyage of the Space Beagle included an all-male crew that had been chemically castrated to keep them content.)

Women also served as astronauts in science fiction movies. The 1950 film Rocketship X-M featured a female crewmember on the first mission to the Moon (which accidentally ended up on Mars). The 1953 movie Project Moonbase started with the premise that the first American astronaut was actually a woman, although the film went out of its way to portray her as qualified for the flight primarily because of her size, not her piloting capabilities, and at one point a general threatens to bend her over his knee and spank her like a child. Perhaps to make up for this sexist treatment, the film also featured a female president.

These are only a few examples from the time period, but they illustrate that the idea of female astronauts was in American popular culture throughout the 1950s and into the 1960s. It was entirely conceivable that a young woman could have seen the cover of Look magazine, or seen Project Moonbase on television or in a theater, and believed it would be possible to become an astronaut—only to write NASA and have their dreams crushed.

A few months ago, one of NASA’s first female astronauts, who flew several shuttle missions, was asked if she had dreamt of becoming an astronaut when she was a little girl. No, she said, because when she was growing up in the 1960s there were no women astronauts, so she didn’t think it was possible. The dreams, and the inspiration—not to mention the flights in space—were left for the men.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments subcommitted to deal with a surge in spam.