The search for life in Congressby Jeff Foust

|

| “We’re making progress as we search for life’s origin, evolution, distribution, and future in the universe,” Cruz said. |

The search for life beyond Earth wouldn’t appear to qualify as one of those issues. Yet, last week, the Senate Commerce Committee’s space subcommittee devoted a hearing to the subject of “The Search for Life: Utilizing Science to Explore our Solar System and Make New Discoveries.” For nearly 90 minutes on what would turn out to be the Senate’s last day in session before a two-week summer break, a handful of senators turned their attention to the subject of NASA’s astrobiology efforts, at least on a broad scale.

The subcommittee’s chairman, Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX), billed the hearing as the second in a series to prepare for a new NASA authorization bill, succeeded the one signed into law in March 2017. (The first hearing, two weeks earlier, was on human exploration of Mars.) “Since the enactment of the NASA Transition Authorization Act of 2017, we have even more reason to be encouraged that we’re on the right path,” he said, referring to a provision in that bill that formally made “the search for life's origin, evolution, distribution, and future in the universe” part of NASA’s mission.

That encouragement, he said, came from evidence of a subsurface lake of liquid water on Mars, published last month in the journal Science. “We’re making progress as we search for life’s origin, evolution, distribution, and future in the universe,” he said. A future NASA authorization bill needs to continue that progress, he said, and “equip NASA with the capabilities that it needs to support science missions and priorities that will lead to discoveries across our solar system.”

“This is one of the gee-whiz parts of NASA,” said Sen. Bill Nelson (D-FL), ranking member of the full Senate Commerce Committee, “and it is complementary with the human missions of NASA.”

That search for life language included in NASA’s charter is broad, and cover a wide range of missions that NASA does. Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA’s associate administrator for science, tried to touch on as many as possible in his five-minute opening statement, from the recently launched TESS mission to look for exoplanets to the upcoming Mars 2020 rover and Europa Clipper missions that will aid in the search for past or present life on those potentially habitable worlds.

“The work of NASA’s science is at the forefront of scientific discovery and innovation,” he said. “The questions we seek to answer affect humanity on a global scale, and focus on our place in the universe. We did we come from? Are we alone?”

Other witnesses narrowed their attention on specific projects. Ellen Stofan, a planetary scientist and former NASA chief scientist who is now director of the National Air and Space Museum, focused on efforts to find evidence of life in the solar system. “There is no other topic I find as exciting or as fundamental to future discoveries that will one day be highlighted in my museum as this one,” she said.

| “There is no other topic I find as exciting or as fundamental to future discoveries that will one day be highlighted in my museum as this one,” Stofan said of looking for evidence of life in the solar system. |

That search included looking for life in the subsurface oceans of icy moons like Europa and Enceladus, as well as seeking signs of past life on Mars. The latter, she argued, could be enabled by human missions to the planet. “If life evolved on Mars in its wet, early Earth-like period, fossilized microorganisms should be present in surface rocks,” she argued. “Biologists, geologists, and chemists on the ground could do more than identify evidence of past life on Mars. They would study its variation, complexity, and relationship to life on Earth much more effectively than our robotic emissaries.”

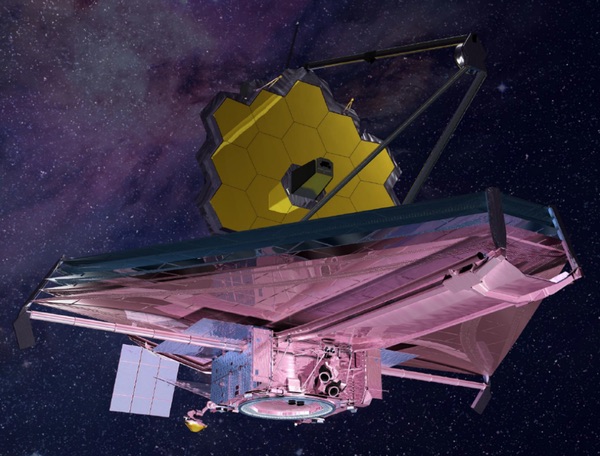

The other two witnesses discussed searching for evidence of life beyond our solar system by studying the habitability of exoplanets using JWST and the Wide-Field Infrared Survey Telescope (WFIRST). “When launched, James Webb Space Telescope will be able to characterize the atmospheres of some of these planers,” said David Spergel, professor of astronomy at Princeton University.

“The WFIRST coronagraph is poised to be the next step in exoplanet characterization,” he said, a thousand times more sensitive than previous instruments that block out light from stars to enable direct observations of planets orbiting them. “It will not only be able to image massive planets around nearby stars, but be a stepping-stone for developing technologies for the next generation of great observatories.”

“Despite the delays and cost growth, the exoplanet community is tremendously enthusiastic because Webb will provide our first capability to study exoplanets in the search for life,” said Sara Seager, professor of physics and planetary science at MIT. She also promoted the concept of a starshade as an alternative means of blocking starlight to enable direct observations of exoplanets by future space telescopes such as WFIRST.

Those ideas all sound great—who isn’t curious about how prevalent life is in the solar system or universe?—but the ideas presented come with their own baggage. As Seager noted, JWST is facing delays that push its launch back from the fall of 2018 to the spring of 2021, increasing its cost through launch by 10 percent to $8.8 billion. That new cost and schedule estimate, announced by NASA in late June, was the subject of a two-part hearing by the House Science Committee spanning two days in late July.

Senators, though, only briefly touched upon the JWST overrun during this hearing. “What explains that incredible increase in cost and delay in deployment?” Cruz asked Zurbuchen more than an hour into the hearing.

“That’s the question I’m asking myself and my team on a regular basis,” Zurbuchen responded. He blamed the increase on several issues, including “excessive optimism,” and development of multiple new technologies, and additional time needed to complete integration and testing work for the spacecraft.

| “Since JWST is an agency-wide priority, these new costs should be spread across the agency,” Spergel argued. “If they are borne entirely by the astrophysics directorate, they’ll have a devastating effect on future missions and the scientific program.” |

Cruz asked if the experience with JWST should cause NASA to revisit the use of cost-plus contracts, like the one prime contractor Northrop Grumman has for the mission, versus fixed-price approaches. Zurbuchen argued that cost-plus was appropriate for one-of-its-kind projects like this. “For new, innovative projects of the type that nobody has ever done, it will be very hard to get a fixed-price contract from a company,” he told the senator.

An open question is how NASA will pay for JWST’s increased costs. At last month’s House hearings, NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine suggested that WFIRST be slowed down to cover those increased costs, a process an agency spokesperson later said could result in delaying WFIRST by about three years. (The administration’s fiscal year 2019 budget proposal for NASA, in fact, called for cancelling the mission entirely, but House and Senate spending bills do provide at least some funding for the mission.)

In his testimony, Spergel sought to soften the blow the JWST delay would have on WFIRST or other NASA astrophysics programs. “JWST’s delays are frustrating for all of us. While the report by the [Independent Review Board] is painful to read at times, I believe that JWST will not only be a transformative astronomical observatory, but will be a flagship for all of NASA,” he said. “Since JWST is an agency-wide priority, these new costs should be spread across the agency. If they are borne entirely by the astrophysics directorate, they’ll have a devastating effect on future missions and the scientific program.”

Other senators didn’t directly address the future of JWST and WFIRST, or planetary science missions with high price tags, like Mars sample return and a follow-on Europa lander mission in early stages of development. But Sen. Ed Markey (D-MA), the subcommittee’s ranking member, used the hearing to call attention to NASA’s Earth science program, which has been the target of budget cuts in the administration’s 2018 and 2019 budget proposals.

“Our investment in NASA’s Earth science and climate research programs and missions must be both abundant and unwavering,” he said in his opening statement, citing concerns about the effects of climate change. “We must be sure NASA’s Earth science program has the resources necessary to provide our scientists with the latest data so that Congress and agencies across the government can combat this problem head-on.”

When it was his turn to pose questions to the witnesses, he again returned to Earth science, seeking assurances from Zurbuchen that NASA’s climate science work will remain a priority in the years ahead, and quizzed the other witnesses to “give an example of how deep space exploration relates to, or helps us, back here on Earth.” The responses were predictable, discussing things like how studying other planets helps put the Earth in perspective, as well as development of spinoff technologies.

Other senators at the hearing focused on topics other than the search for life, asking about issues ranging from space weather to planetary defense to the use of the decadal survey approach to identify scientific priorities and corresponding missions. The witnesses sought to offer different arguments for supporting their missions, including international competition.

| “I have been very impressed by the investments the Chinese are making in space science. They were really not even significant players 10 years ago,” Spergel said. “Looking to where they might be a decade from now, if we stop investing, they will be the leaders.” |

Spergel, for example, discussed China’s growing capabilities in space science. “When I was in Beijing last year, I was impressed by China’s plans to launch a large space telescope off of its space station with its primary focus studying dark energy,” he said. “This telescope will have the world’s largest space camera and use Chinese military technology to construct a large off-axis telescope.” He added, though, that NASA’s WFIRST remained the “premier” upcoming dark energy mission.

Cruz asked Spergel if he thought the US was leading in space science. “I think we are leading the world,” he said, but mentioned capabilities in Europe and China. “I have been very impressed by the investments the Chinese are making in space science. They were really not even significant players 10 years ago. Looking to where they might be a decade from now, if we stop investing, they will be the leaders.”

In the halls of Congress, that’s an argument that might resonate better with members that high-minded questions about whether we’re alone in the universe when it comes to winning funding for future missions that seek to answer those questions.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments subcommitted to deal with a surge in spam.