Review: The Astronaut Makerby Jeff Foust

|

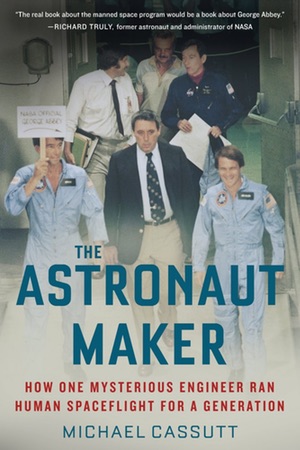

| Abbey, at the time of his forced retirement, had become one of the most powerful, and polarizing, figures in NASA. |

It brought back memories of similar events in the US nearly two decades earlier. In a statement released late on a Friday in February 2001, NASA announced that the agency had reassigned George Abbey, the director of the Johnson Space Center, to be the “special assistant for international programs,” a newly created post with little power and authority. It effectively marked the end of Abbey’s career, and less than two years later he formally retired from NASA.

Abbey, at the time of his forced retirement, had become one of the most powerful, and polarizing, figures in NASA—some wondered if he, rather than administrator Dan Goldin, was really running the agency—but also one who worked largely out of public view. He was particularly influential with the astronaut corps, with the perceived ability to either give his favorites plum flight assignments or freeze out those who fell into disfavor.

Abbey, though, was far more than a manager who handled shuttle flight assignments. His career at NASA stretched from Apollo to the International Space Station, playing key roles in both those programs, as well as the shuttle and other aspects of space policy. That career is described in detail in The Astronaut Maker, the new biography of Abbey by Michael Cassutt.

George William Samuel Abbey—he and his siblings all had two middle names— was born and raised in Seattle. He had planned to go to the University of Washington there on a Naval ROTC scholarship, but an older brother secured him a slot at the Naval Academy instead. Interested in flying, but not wanting to spend up to two years assigned to a ship before being eligible to apply to flight school, he accepted a commission in the Air Force upon graduation and soon was piloting both airplanes and helicopters before working on Dyna-Soar.

After the Air Force cancelled Dyna-Soar, Abbey was assigned to the Manned Spaceflight Center in Houston to help NASA manage the Apollo program: a position he didn’t want at first, but one which he excelled at, and liked so much he resigned from the Air Force to stay at NASA. Abbey, with his piloting background and technical experience, also sought to become an astronaut, applying through the Air Force in 1966 only to have his application rejected because he had not attended the service’s test pilot school.

While not becoming an astronaut himself, Abbey did more than just about anyone in the agency’s history to shape the astronaut corps. Named director of flight operations at what was now called the Johnson Space Center in 1976, he went to work on a new astronaut recruitment campaign to prepare for the shuttle program, specifically seeking minority and women candidates. Through the late 1980s, Abbey oversaw who was selected as astronauts and who would be assigned to shuttle flights, the role he is perhaps best remembered for at NASA.

In the late 1980s he was detailed to NASA Headquarters, an assignment that, like his original posting to Houston, he did not desire but later found essential. During his time in Washington he was involved in many major efforts, largely behind the scenes, from the Synthesis Group study on space exploration to the National Space Council. After what was effectively the firing of NASA administrator Richard Truly, Abbey became the special assistant to his replacement, Dan Goldin. The two worked so well together, Cassutt writes, “that NASA insiders were calling them ‘Chief Dan George’,” effectively running the agency together. (Mark Albrecht, the executive secretary of the National Space Council at the time of Goldin’s hiring, refuted the “mythology” that Abbey had somehow conspired to get Truly fired and pick Goldin. Instead, Albrecht said that Goldin “was my number one pick to head NASA” and that he introduced Abbey to Goldin shortly before Goldin was formally nominated.)

Abbey helped spearhead efforts to keep the space station program from being cancelled, and bring in the Russians to what became the International Space Station. Abbey soon returned to JSC, first as the center’s deputy director and later as its director, charged with managing both the shuttle and station programs. That meant dealing with problems with the station program and putting pressure on contractors, and others within NASA, to deliver.

| Abbey became the special assistant to Truly’s replacement, Dan Goldin. The two worked so well together, Cassutt writes, “that NASA insiders were calling them ‘Chief Dan George’,” effectively running the agency together. |

Cassutt argues that Abbey created too many enemies within NASA over this time, ultimately leading to a falling out with Goldin. Albrecht likened the demise of the Goldin-Abbey partnership to the relationship between Henry II and Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury—only rather than ending with Becket’s murder, this relationship ended with Abbey’s reassignment.

The Astronaut Maker is largely a sympathetic biography of Abbey. While Cassutt acknowledges the criticism Abbey received, including his “Dark Lord” mystique, he also emphasizes the work he did to make the astronaut corps more diverse and more closely tie JSC to the broader community (such as hosting longhorn cattle on JSC property for a local school system.) Abbey may have made enemies, but he had many supporters as well.

The book largely focuses on Abbey’s professional career. Cassutt speeds through Abbey’s childhood in a few pages, and while offering glimpses of his personal life—marriage and raising a family—there’s far more about Abbey the NASA manager. For example, his divorce from his wife of a quarter-century, Joyce, is mentioned only in passing in a couple sentences, without any mention of the reasons for the separation.

Overall, though, the book helps better understand one of the key individuals in the history of NASA’s human spaceflight efforts, a person who for man had been shrouded in mystery and mythology.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments subcommitted to deal with a surge in spam.