When spacecraft dieby Jeff Foust

|

| “We’re not going to be surprised, whether it’s a day from now or a month from now or two months from now, when we find out Kepler has run out of fuel,” said Hertz. |

For now, Kepler seems to be in more immediate peril. In July, and again in September, the spacecraft interrupted observing campaigns because of issues linked to declining amounts of fuel. Both times controllers were able to downlink the data the spacecraft collected during those truncated imaging campaigns and then decided to start the next observing campaign, knowing that the spacecraft was running on fumes.

“We’re not going to be surprised, whether it’s a day from now or a month from now or two months from now, when we find out Kepler has run out of fuel,” said Paul Hertz, director of NASA’s astrophysics division, during an October 22 meeting of the agency’s Astrophysics Advisory Committee.

Just a week earlier, he said, Kepler had started its latest observing campaign, called Campaign 20. Past observing campaigns by Kepler, where it looks at a single part of the sky, had lasted up to 80 days, but he suggested controllers would cut those observations short if there were signs the spacecraft was nearly out of fuel, so it could transmit back those final observations.

In fact, even as Hertz spoke, Kepler was experiencing problems. The project announced October 23 that the spacecraft had entered what it called a “no-fuel-use sleep mode” when controllers checked in with the spacecraft October 19, and were investigating the problem.

As of late last week, there were no updates on the health, or the future, of Kepler. “NASA is still analyzing the data to determine the next steps, and will provide an update when we can,” a project spokesperson said.

Kepler needs to use thrusters because of the failure of two of its four reaction control wheels that ended the spacecraft’s primary mission in 2013. The spacecraft has since relied on its remaining reaction control wheels and its thrusters, along with ingenious use of solar pressure on the spacecraft, to allow it to point at different areas of the sky for weeks at a time, rather than the sole focus on a single part of the sky of Kepler’s original mission. That will no longer be possible, though, when Kepler exhausts its hydrazine.

Dawn is in a similar predicament: it has relied on its hydrazine thrusters for attitude control once its reaction control wheels have failed. The spacecraft, in orbit around the dwarf planet Ceres, is still operating, but is also running out of hydrazine.

“To within our current uncertainty, there’s zero usable hydrazine remaining,” said Marc Rayman, chief engineer and mission director for Dawn, during a talk in early October at the International Astronautical Congress in Bremen, Germany. At the time of his talk, he said current projections called for running out of hydrazine in mid-October, but as of late October the spacecraft was still functioning.

| “To within our current uncertainty, there’s zero usable hydrazine remaining,” said Rayman of Dawn. |

Rayman said mission planners are working on developing sequences for operating the spacecraft into December should their estimates of the remaining hydrazine turn out to be wrong. “But, you know what, we’re probably not wrong,” he said. “But we’re going to continue as long as we can.”

Dawn, which launched more than a decade ago and orbited the asteroid Vesta before arriving at Ceres, is wrapping up an extended mission that put the spacecraft into an elliptical orbit, bringing it within about 35 kilometers of the surface of Ceres. That increased demands on the attitude control thrusters, but has provided scientists with high-resolution images and other data of selected regions of Ceres.

Dawn’s fate is complicated by planetary protection protocols, given that Ceres has water and organics, two of the key ingredients for life. NASA requires that Dawn remain in orbit for at least 20 years after the end of its mission before impacting its surface.

That should not be a problem, Rayman said. Simulations of the spacecraft’s orbit show a 99 percent chance it will still be in orbit after 50 years, the longest the simulations have been run. “The lifetime in orbit is likely significantly longer than that.”

That 20-year requirement, he noted, is not based on factors like radiation exposure sterilizing the spacecraft but rather to provide time for NASA or another agency to mount a follow-up mission to study the dwarf planet before Dawn impacts and contaminates Ceres. “There are good arguments for revisiting such criteria,” Rayman said, “but that’s not a topic for here.”

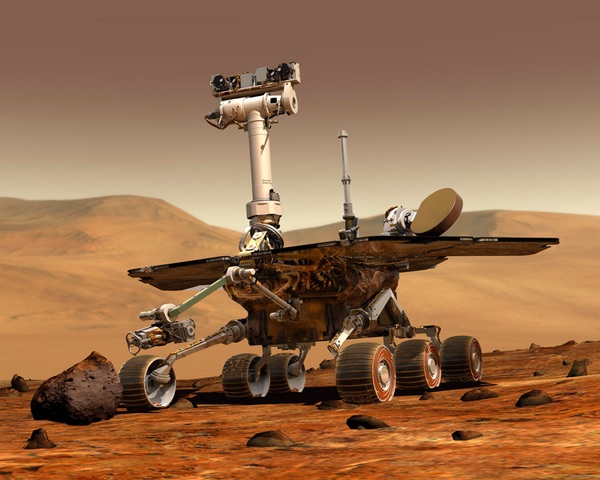

An illustration of Opportunity, one of the twin Mars Exploration Rovers, which has been out of contact with the Earth since a dust storm in early June. (credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech) |

The impending demise of Dawn and Kepler is no surprise: project officials knew for months, even years, that the spacecraft would be running out of hydrazine by late 2018, and planned those missions accordingly. At this point, each additional day of operation either spacecraft can provide is a bonus for missions that long exceeded their original lifetimes.

The situation is different for Opportunity rover on Mars. It, too, has long exceeded the 90-day mission lifetime for it when it landed on the Red Planet in January 2004. Unlike Dawn and Kepler, though, there’s been no consumable like hydrazine setting an upper limit on its life; rather, it’s been the health of the rover as it suffers the wear-and-tear of Martian surface operations.

Opportunity was still working well in early June when a powerful dust storm developed and spread across the planet. That storm darkened the skies, depriving the rover of solar power. (The rover Curiosity, with its radioisotope thermoelectric generator, was not similarly affected.) Controllers could only watch and wait for the skies to clear to see if the rover survived the storm (see “A fading Martian Opportunity”, The Space Review, September 4, 2018).

By early September, skies above the Opportunity landing site had cleared to a point where the rover would receive enough sunlight to generate power again. NASA kicked off what it called an “active listening” effort at this point, transmitting commands in the blind to the spacecraft to help it resume operations if was not able to do it self, and listening for any response.

Opportunity, though, has remained silent, and NASA is considering ending that active listening effort. “We intend to keep pinging Opportunity on a daily basis for at least another week or two,” said Lori Glaze, acting director of NASA’s planetary science division, during an “agency night” presentation at the American Astronomical Society’s Division for Planetary Science meeting a week ago in Knoxville, Tennessee.

| “The batteries may be getting too cold, and that may be too much for the little rover that could,” Glaze said of Opportunity. |

When NASA announced its plans for that active listening effort in late August, it said it would attempt that for only about 45 days. “If we do not hear back after 45 days, the team will be forced to conclude that the sun-blocking dust and the Martian cold have conspired to cause some type of fault from which the rover will more than likely not recover,” John Callas, Opportunity project manager, said in a statement outlining those plans then.

Back in August, some former rover engineers and controllers criticized the plans, saying the 45-day period was too short and started too early, when there was still some degree of dust left over in the atmosphere from the storm. “I’ll be blunt: 45 days is absurdly short, and certainly arbitrary,” said Scott Maxwell, a former Mars rover driver, in a tweet. He thought the effort should have waited until skies were clearer, and lasted longer.

While project officials said the 45-day period for active listening is driven by the expectation that the spacecraft likely has failed if it doesn’t respond by the end of the window, there’s another factor as well: NASA’s next Mars lander, InSight, will arrive at the planet November 26, and the agency wants to start getting ready for that.

“We want to wind that down before InSight gets to Mars and make sure all our orbital assets are focused on a successful landing of InSight,” Glaze said last week.

However, Opportunity got a respite as this article was being prepared for publication. Late on October 29, JPL announced that NASA “will continue its current strategy for attempting to make contact with the Opportunity rover for the foreseeable future,” citing the potential for winds in the coming months to blow dust off the rover’s solar panels. “The agency will reassess the situation in the January 2019 time frame.”

However, Glaze said last week that the odds of hearing anything might still be low since, with the blanket of dust that had moderated temperatures gone, conditions are back to getting very cold at night, with decreasing sunlight as well because of the seasonal cycle. “The batteries may be getting too cold, and that may be too much for the little rover that could,” she said.

NASA hasn’t given a firm timeline for ending efforts to listen for Opportunity’s signals and this conclude the rover is dead. In late August, a JPL spokesperson, DC Agle, said those efforts would likely last at least through January. “The most likely recovery is for Opportunity to autonomously wake up and talk to us,” Agle said. “That’s why we are listening all that time.”

But, eventually, the sound of silence from Opportunity will become deafening, and it will be time to move on to the other missions at Mars, and elsewhere in the solar system, that are still alive and returning data that is changing our understanding of the universe and our place in it.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments subcommitted to deal with a surge in spam.