A distant flybyby Jeff Foust

|

| May agreed to write a song, even though he said it was something of a challenge. “I can’t think of anything that rhymes with Ultima Thule.” |

So, then, what to do with NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft and its latest achievement, a flyby of a distant Kuiper Belt object, formally designated 2014 MU69 and nicknamed by the mission Ultima Thule? The spacecraft’s closest approach to the tiny object, 6.6 billion kilometers from Earth, would take place just 33 minutes after midnight, Eastern time, on New Year’s Day.

At the Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland, mission control for New Horizons, the answer was to throw a party. As New Horizons hurtled towards Ultima Thule at 14 kilometers per second, the mission team, invited guests, and the media gathered in a large auditorium at the center for a celebration unlike any other New Year’s Eve event in the world.

The event was, well, eclectic. There were some conventional aspects, such as updates about what the spacecraft was doing—or, rather, should be doing, since it was not in contact with the Earth at the time—as it approached the object, and a panel discussion about exploration of small bodies in the solar system in general. There was also, though, a talk by a paleontologist, Kenneth Lacovara, who likened Ultima Thule to “a fossil in the sky.” There was also a singalong with the repeated refrain “It is amazing! I am amazed!” that was followed by a talk by Walter Alvarez, the geologist who codiscovered the iridium layer at the K-T boundary that provided evidence of the impact that wiped out the dinosaurs 65 million years ago. The evening was a mashup of New Year’s Rockin’ Eve and TED.

Shortly before midnight, the audience moved into a neighboring reception area where, equipped with traditional party favors and glasses of champagne, they rang in the new year at midnight. Thirty-three minutes later, they did another countdown and celebration, this time to mark New Horizons’ closest approach to Ultima Thule, passing 3,500 kilometers away from the object.

In between, the crowd got to listen to the world premiere of a new song by Brian May, the guitarist for Queen who also has a doctorate in astrophysics and is a member of the New Horizons science team, specializing in 3-D imagery. “I’m here to work,” he told reporters earlier in the day. But, he added, Alan Stern had called him several months earlier with a request: “Can you make some music for the Ultima Thule flyby?”

He agreed to, even though he said it was something of a challenge. “I can’t think of anything that rhymes with Ultima Thule.”

The next morning, the celebration turned to anticipation. Several hours after closest approach, New Horizons was programmed to transmit a “health and safety” check back to Earth, a burst of telemetry that would contain no science data but instead information on the performance of the spacecraft. At the spacecraft’s distance some six light-hours from Earth, that signal would arrive around 10:30 a.m. Eastern on New Year’s Day.

So the same revelers that marked the new year and the flyby hours earlier were back in the APL auditorium to watch a feed from the mission control center in another building at the lab. There was a hush as the room hung on every word spacecraft controllers spoke as the 15-minute communications window opened.

The mood lightened, though, with each “green” report from various subsystems being greeted with cheers. New Horizons had operated as expected. “We have a healthy spacecraft,” said Alice Bowman, the New Horizons mission operations manager. “We’ve just accomplished the most distant flyby. We are ready for Ultima Thule science transmission.”

Alan Stern, principal investigator for New Horizons, leads the mission team into the auditorium at APL after controllers confirmed the flyby was a sucecss. (credit: NASA/Joel Kowsky) |

So why go through all the effort to fly a spacecraft past a distant object, only a few tens of kilometers in diameter? The flyby was a bonus for a spacecraft launched in 2006 with the primary mission of flying by Pluto and its moons, which it achieved in July 2015. Ultima Thule itself wasn’t discovered until 2014, part of a concentrated effort by project scientists using the Hubble Space Telescope to look for any Kuiper Belt objects in range of New Horizons after its flyby.

No spacecraft had yet flown past a small body in the Kuiper Belt, the ring of small icy objects in the outer solar system believed by many scientists to be remnants from the formation of the solar system more than 4.5 billion years ago. “The Kuiper Belt is just a scientific wonderland,” said Alan Stern, principal investigator for New Horizons, during a briefing prior to the flyby. “From a scientific standpoint there’s nothing like this.”

| “The Kuiper Belt is just a scientific wonderland,” said Stern. |

Ultima Thule is part of a family of Kuiper Belt objects called “cold classicals.” The name, scientists said, has nothing to do with their temperature—although they are indeed extremely cold given their distance from the Sun—but the fact that their orbits, circular and in the same plane as the solar system, indicate that they have not been altered since the solar system’s formation.

“It’s probably the most primitive object ever encountered by a spacecraft,” New Horizons project scientist Hal Weaver said of Ultima Thule. “It’s the best possible relic of the solar system’s formation out at those distances.”

The full story of Ultima Thule will play out over many months. Given the spacecraft’s limited power and extended distance, it will take about 20 months to return all of the data collected by New Horizons during the flyby. In the days after the flyby, only a few minutes and other data had made it back, but what scientists could see so far was lending credence to the believe that the object was ancient and pristine.

That confirmation came in the form of the shape of the object. Prior to the flyby, Ultima Thule was not resolved in images from the Hubble Space Telescope, appearing as only a point source. Other telescopes also could not determine its shape. The object’s “lightcurve,” or change in brightness as a function of time, was flat in observations taken by New Horizons on approach, offering no clues about its shape. The best image prior to closest approach, taken New Year’s Eve, showed an elliptical object, but scientists couldn’t yet determine if it was simply a single extended object or two objects closely orbiting one another.

“That image is so 2018,” Stern said at a January 2 briefing, revealing one taken shortly before closest approach and transmitted back to Earth later New Year’s Day. It revealed that Ultima Thule was a “contact binary”: two bodies touching one another. The larger body, dubbed “Ultima,” is 19 kilometers across, while smaller “Thule” is 14 kilometers across.

The contact binary shape of the object suggests it came together slowly through accretion, as expected from models of solar system formation. “What we think we’re looking at is the end product of a process that probably took place only a few hundred thousand or maybe a few million years at the very beginning of the formation of the solar system,” said Jeff Moore, a member of the mission science team from NASA’s Ames Research Center.

The two bodies came together at a very low speed, he said, on the order of a few kilometers per hour, slow enough to preserve each object. “If you had a collision with another car at those speeds, you may not even bother to fill out the insurance forms,” he said.

“What we’re looking at is basically the first planetesimals,” Moore said. “These are the only remaining basic building blocks.”

With the limited data returned so far, scientists couldn’t say too much more about Ultima Thule. The object has a reddish appearance, which would be expected if the object had an icy surface altered over billions of years by radiation. A search for moons and an atmosphere turned up empty, although more images yet to be returned will be needed to rule out any small moons in the vicinity of the object. While the images showed some variations in brightness on the surface, and hints of topography like ridges and craters, Stern cautioned not to read too much into the limited data. “We’re going to see Ultima in much higher resolution” in later images, he said.

Brian May, the Queen guitarist who also has a doctorate in astrophysics, meets with the media during flyby events at APL. (credit: NASA/Bill Ingalls) |

The only problem during the flyby was not with the spacecraft itself but the nickname of the object that it flew by. In the months leading up to the flyby, the mission ran a competition for an informal name—one not sanctioned by the International Astronomical Union, the body responsible for approving names for solar system objects and features on their surfaces—to be used during the flyby. Such a name, they argued, would be easier than the official designation of 2014 MU69.

| “Just because some bad guys liked that term,” Stern said of past uses of the Ultima Thule name, “we’re not going to let them hijack it.” |

Ultima Thule didn’t come out on top in the naming competition, finishing seventh behind names ranging from Mjölnir (Thor’s hammer) to nuts like Almond, Cashew, and Peanut, given the irregular shape scientists expected to see. (It did finish just ahead of Tiramisu, the dessert.) The mission, though, selected Ultima Thule, a name dating back to classical times, for its connotation of being “beyond the borders of the known world,” reflecting the object’s distance from Earth.

But immediately after the flyby, some people noted the name had also been used by the Nazis, appropriated from those earlier accounts to be the mythical homeworld of the Aryan race. That connection wasn’t widely known earlier, beyond a single Newsweek story, but in days after the flyby some called on NASA and the mission to revert to 2014 MU69 or use a different nickname for the object.

Stern defended the name during a press conference January 2. “The term ‘Ultima Thule,’ which is very old—many centuries old, possibly over a thousand years old—is a wonderful meme for exploration, and that’s why we chose it,” he said. “Just because some bad guys liked that term, we’re not going to let them hijack it.”

Thomas Zurbuchen, the NASA associate administrator for science, also backed the continued use of the name. “If there is a connection, it is very tenuous,” he said of any Nazi ties to the name in comments after the press conference. He emphasized the “positive message” of the name and that a search conduced prior to its selection turned up a wide range of other uses of the name. They range from bands to Finnish glassware to a lodge in northern Alaska.

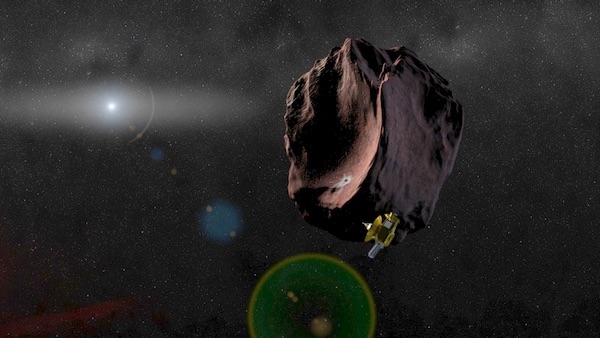

An illustration of New Horizons flying past a Kuiper Belt object. The mission hopes to achieve another such flyby in the 2020s. (credit: JHUAPL/SwRI) |

After all the excitement fades from this flyby, will there be an encore? Project officials hope so—if they can find a new target.

“We have power and fuel to run this bird into the mid-2030s, maybe longer,” Stern said at a briefing prior to the Ultima Thule. “What the science team and the mission team want to do after we get all the data back from Ultima is to propose to NASA to explore the outer parts of the Kuiper Belt.”

That proposal would come in the next senior review of planetary science missions, in 2020, around the time New Horizons completes returning data collected from this flyby. That proposal will involve the search of objects in range of New Horizons, given its available fuel to adjust its trajectory, and planning for any flyby.

| “The big bottleneck is being able to send data back,” said Weaver. “We can’t possibly take thousands of images and send those all back.” |

The difficulty will be in finding an object. Any target will be further away from the Sun and likely dimmer, making it hard for even the largest telescopes to find it. “To look for it we’ll use every tool that’s possible,” Stern said, including both Hubble and new large groundbased telescopes, as well as possibly the James Webb Space Telescope after its 2021 launch.

The best tool for finding a new target, though, may be New Horizons itself. The spacecraft’s Long Range Reconnaissance Imager, or LORRI, first saw Ultima Thule in August, when the spacecraft was more than 160 million kilometers away. Stern added it may have been possible to see it even sooner.

Turning New Horizons into a Kuiper Belt object hunter will require changes to the spacecraft’s software. “The big bottleneck is being able to send data back,” said Hal Weaver, given low data rates. “We can’t possibly take thousands of images and send those all back.”

Weaver said that, even before the Ultima Thule flyby, the project team was looking at changes to software on New Horizons allowing it to add together images and sending back only the combined image, allowing scientists to spot the moving objects that could be candidates for a flyby.

However, while the mission had several years to prepare for the Ultima Thule flyby, based on its 2014 discovery, an object detected by the spacecraft itself will likely be found only months before a flyby. “What we’ll have to do is build a generic flyby mode and do a flyby on warning if we detect it from onboard the spacecraft,” Stern said.

New Horizons will remain in the Kuiper Belt through the late 2020s, giving the project plenty of time to find a target. But, first things first. We’ve got to focus on Ultima Thule right now,” Weaver said just before the spacecraft made its close approach to that body. “But right after the flyby we’ll jump on this problem.”

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments subcommitted to deal with a surge in spam.