Rethinking satellite servicingby Jeff Foust

|

| “We’re moving right along,” DARPA’s Kennedy said of RSGS in November. “We expect to launch in 2021.” |

There’s also an emerging market for satellite servicing in the form of operators of commercial communications satellites in geostationary orbit (GEO). In the last few years orders of new GEO satellites have plummeted as operators weigh the impact of new technologies, like high-throughput satellites and proposed low Earth orbit constellations. The ability to extend the lives of their existing satellites for a fraction of the cost of a new one offers them a chance to buy time regarding their next major investments, either in GEO or in LEO.

So with the momentum building for satellite servicing, it was a surprise Wednesday morning when one of the major companies in this emerging market decided to bail out. In a brief statement, Space Systems Loral (SSL), a division of Maxar Technologies, announced it was terminating an agreement with DARPA on a program called Robotic Servicing of Geosynchronous Satellites (RSGS).

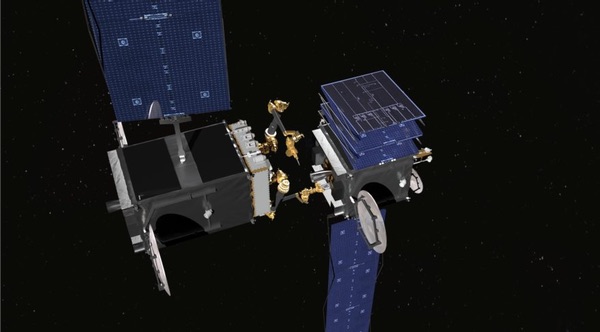

DARPA awarded the program to SSL in 2017 through an other transaction agreement, an approach similar to NASA’s Space Act Agreement that allows for partnerships with companies rather than traditional contracting arrangements. Under the agreement, SSL would provide a spacecraft bus, similar to the ones it builds for GEO satellites, while DARPA would provide the robotic servicing payload. After an on-orbit demonstration, SSL would be free to use the spacecraft for commercial servicing through a new company called Space Infrastructure Services partially owned by SSL.

Work on the RSGS program appeared to be going well. Last August, DARPA announced the robotic servicing payload, being developed by the Naval Research Lab, has passed its preliminary design review, showing it would be able to service at least 20 satellites once in orbit. “We are well on our way to significantly improving the resiliency and functionality of government and commercial spacecraft in geosynchronous orbit,” Joe Parrish, DARPA’s program manager for RSGS, said in a statement then.

“We’re moving right along,” Fred Kennedy, director of DARPA’s Tactical Technology Office, said during a talk at a November meeting in Washington of the Consortium for Execution of Rendezvous and Servicing Operations, or CONFERS, a group created with DARPA’s support to establish best practices regarding satellite servicing. “We expect to launch in 2021. We have an agreement with the Air Force to go do that launch. I’m very pleased to say we’re on track. Hopefully we will stay on track.”

Then—quite suddenly, at least to most in the industry—it went off track. SSL said in its statement that it was terminating the RSGS agreement because it needed “to focus its resources on ensuring optimal returns when weighed against other capital priorities, such as WorldView Legion,” a remote sensing satellite system being built by SSL for DigitalGlobe, another division of Maxar.

A company official also blamed the decision on economics. “While disappointed that we are unable to find an economically viable path to support RSGS and meet our return criteria, we are dedicated to partnering with the US government to realize the full potential of in-space robotic servicing of spacecraft, as well as assembly and manufacturing in space,” said Richard White, president of SSL Government Systems, in the statement.

SSL is involved with another satellite servicing program, called Restore-L, funded by NASA, That program seeks to develop a spacecraft for satellite servicing in low Earth orbit, with an initial goal of refueling the Landsat-7 spacecraft. That program, though, is run as a more conventional contract, with NASA putting up the money and, unlike RSGS, no commercialization plans.

| “We’re looking at all these key building blocks for servicing,” Sauzay said. “But one of the key questions, obviously, is the business case: how it can happen, how it can work.” |

DARPA said it would find a way to press ahead with the RSGS program without SSL. “The design of the robotic payload is expected to be adaptable to a variety of potential spacecraft buses,” the agency said in a statement. “Over the next few months, DARPA will be evaluating multiple options for the RSGS program going forward, including a potential recompetition or restructure of the program.”

The timing of the decision was surprising, but the fact that SSL is revisiting some of its programs because of financial issues is not. With the decline in GEO satellite orders, SSL executives said in recent months they’ve considered divesting itself of that business and focusing more on smaller satellites. In December, the company sold some of what may be its valuable asset: real estate in Palo Alto, California, in the heart of Silicon Valley.

But if the business case for satellite servicing doesn’t work for SSL, does that raise a red flag for the industry in general? Prior to SSL’s decision, more companies were showing an interest in satellite servicing, although without the support of a government agency like NASA or DARPA.

One example is Northrop Grumman Innovation Systems, the former Orbital ATK, which has been working for several years on its Mission Extension Vehicle (MEV). Less complex than DARPA RSGS concept, the MEV would attach to a satellite in GEO and handle maneuvering and stationkeeping.

Privately developed, the first MEV is being completed for launch later this year, while Northrop Grumman builds a second MEV. The MEVs will be operated by a wholly owned subsidiary, SpaceLogistics LLC, with plans for more advanced systems, including pods that could be attached to satellites by a larger spacecraft.

“It’s sort of what we think of as the baby step, the minimum risk entry into this market area,” said Northrop Grumman’s Jim Armor of the MEV at the CONFERS meeting in November. The MEV is based on the same bus the company uses for GEO satellites. A single MEV, he added, could operate for more than 15 years in orbit, servicing multiple satellites.

Other companies best known as satellite manufacturers are also wading into the satellite servicing field. “It is time for our industry to move from the age of pioneers to the commercial age,” said Emmanuel Sauzay, director of commercial space at Airbus, at the CONFERS meeting. “We think that on-orbit servicing is probably the way for us to change the way we will manufacture satellites in the future.”

Airbus unveiled last fall a new initiative called O. CUBED Services to do pursue various on-orbit servicing initiatives, including servicing satellites in GEO and deorbiting satellites in LEO. For now, though, those efforts are still in the planning stages.

“We’re looking at all these key building blocks for servicing,” Sauzay said. “But one of the key questions, obviously, is the business case: how it can happen, how it can work.”

| “It’s like trying to buy an iPhone. You try to time the market,” La Rosa said. |

Another satellite manufacturer is keeping an open mind about satellite servicing. “Thales Alenia Space, to be honest, didn’t really see a real existing market for this type of activity,” Max La Rosa, a business development director at the company, said of satellite servicing at the CONFERS meeting. “We kept the idea in a drawer hoping for future applications.”

That assessment is changing, he said. “It’s like trying to buy an iPhone. You try to time the market,” he said. “From that perspective, we’re starting to have the feeling at Thales that, even at this conceptual stage for now, the market demand for on-orbit servicing may have the same pace.”

In the case of Thales, he said the company would likely skip near-term steps like satellite life extension, because it would be late to the market. “We think, at least from our perspective, that it’s better to look forward to the second generation of on-orbit servicing,” he said, such as replacing satellite payloads or on-orbit assembly. Such systems, though, might not be ready until the mid-2020s in even an optimistic scenario, he said.

None of these companies, in the months since the CONFERS meeting, have suggested second thoughts about pursuing satellite servicing, either in the near or long term. And even amid problems with other space companies outside of satellite servicing—including recent layoffs at SpaceX, Stratolaunch, and Virgin Galactic—some advised not to read too much into SSL’s decision to drop out of the RSGS program.

“I think that’s maybe symptomatic of some broader financial issues that are going on with Maxar today,” said Andrew Rush, president and CEO of Made In Space, during a panel discussion on the state of the space industry held by the Space Foundation in Washington hours after SLS announced it was terminating its RSGS agreement. He and other panelists remained bullish about the space industry in general, and did not seem fazed about SSL’s decision regarding RSGS.

“I don’t think that goes to the efficacy of the RSGS program, of satellite servicing,” he continued. “I think we’ll see that continue to blossom.”

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments subcommitted to deal with a surge in spam.