Cost challenges continue for NASA science missionsby Jeff Foust

|

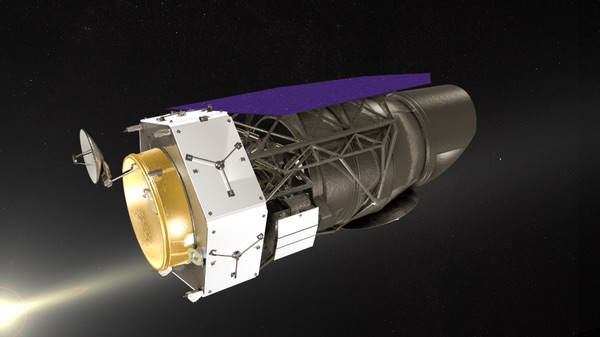

| There was little obvious concern about the future of WFIRST despite the threat of cancellation hanging again over the mission. “We know it’s going to be great when it works,” said Mather. |

NASA’s detailed budget request, released last week, said the decision to cancel WFIRST was due to “its significant cost and higher priorities within NASA, including completing the delayed James Webb Space Telescope.” JWST, of course, has suffered its own set of problems that pushed back its launch from the fall of 2018 to March of 2021 and cost its cost to grow by 10 percent to $8.8 billion.

The good news is that, for now, JWST is remaining on that revised budget and schedule. “Mission success is what our primary goal is,” said Dennis Andrucyk, deputy associate administrator for science, of JWST during a presentation at the American Astronautical Society’s Goddard Memorial Symposium last week. “It’s a very expensive mission, but I think the resulting science is going to change the way we think about astrophysics.”

There was, at that two-day symposium, little obvious concern about the future of WFIRST despite the threat of cancellation hanging again over the mission. Speakers discussed the mission and the science it would do as if it was a fait accompli. “We know it’s going to be great when it works,” John Mather, a Goddard astrophysicist and Nobel Laureate in Physics, said of WFIRST in a speech at the conference.

In an earlier panel at the conference on astrophysics research, Adam Riess, a professor at Johns Hopkins University and another Nobel Laureate, talked up the potential of WFIRST. “It is, I’m told, on schedule and on budget,” he said of the mission. WFIRST, he said, “will be a fantastic missing tool in our toolkit of space astrophysics,” particularly in unraveling the mysteries of dark matter and dark energy. He, like Mather, made no mention of the fact that WFIRST was, for the second year in a row, in danger of cancellation

But given the problems with JWST, the top-ranked flagship mission in the 2000 astrophysics decadal survey, and WFIRST, the top-ranked flagship mission in the 2010 decadal survey, should astronomers rethink the viability of such missions as they begin work on the 2020 decadal survey?

Riess didn’t think so. “I think we should continue to be bold with these missions,” he said. “When we can imagine very exciting, very bold programs, and we can make the case of how interesting and exciting they are, then I think the funding will materialize.”

“Are we going to be able to afford what we want to do in the future?” Mather asked in his talk. He was optimistic, given technological advances that have increased the capabilities of telescopes. “I think yes. The future is pretty long and exponential growth matters.”

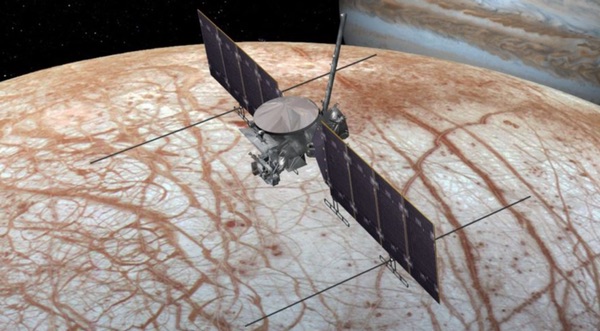

Citing cost growth and other risks, NASA removed an instrument from the Europa Clipper mission, a decision that did not sit well with some scientists. (credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech) |

Overruns mar Mars 2020, Europa Clipper instrument clipped

The budget proposal offered mixed news for planetary science missions. The budget included continued funding for the Europa Clipper mission to that icy moon of Jupiter, the next planetary flagship mission after the Mars 2020 rover. The budget also included, for the first time, funding to start initial work on future Mars sample return missions: one to collect the samples that the Mars 2020 rover caches and place them in Mars orbit, and another to collect that sample canister in orbit and return them to Earth.

| “I think we should continue to be bold with these missions,” Riess said. “When we can imagine very exciting, very bold programs, and we can make the case of how interesting and exciting they are, then I think the funding will materialize.” |

But the detailed budget proposal also confirmed rumors that had been circulating in the planetary science community for months: Mars 2020 was over budget. The budget request stated that problems with two of that mission’s instruments, the Planetary Instrument for X-ray Lithochemistry (PIXL) and Scanning Habitable Environments with Raman & Luminescence for Organics & Chemicals (SHERLOC), along with the rover’s sample caching system, “have resulted in mission cost growth” for Mars 2020. The proposal didn’t disclose the magnitude of the cost overrun or how NASA would pay for it, saying those details will be disclosing in a forthcoming operating plan for fiscal year 2019.

The disclosure of that overrun came on the first day of the 50th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference outside Houston. At a NASA town hall meeting that evening, agency officials acknowledged the issue. “Yes, there has been cost growth” with Mars 2020, said Lori Glaze, acting director of NASA’s planetary sciences division. “It is less than 15 percent over the agreed-upon cost for [Mars] 2020.” That previous cost agreement pegged the mission at $2.1 billion, plus $300 million for its first Martian year of operations.

Glaze said that NASA would seek cost savings within the mission itself, such as deferring some work. “There’s been a very strict approach in trying to look to the project first for economies, and find ways to cover some of the cost growth, and, outside of that, look to going to the Mars program,” she said. That would include the funding line called Mars Future missions that will host the Mars sample return work.

Glaze said later that it was unlikely NASA would take major steps, like removing one of instruments that triggered the overrun, because that would offer little in the way of savings so late in the mission’s development. “There’s already an enormous amount of hardware built and integrated and being tested for Mars 2020,” which is scheduled for launch in July 2020, she said.

It’s a different situation for Europa Clipper. In early March, NASA announced it was removing one instrument, a magnetometer called Interior Characterization of Europa Using Magnetometry (ICEMAG), from the mission. The instrument would have measured the magnetic field around Europa, a way of depth and salinity of the moon’s subsurface ocean.

NASA officials, including Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for science, said they decided to remove ICEMAG because of technical problems that resulted in growing costs for the instrument that exceeded a “cost trigger” for it established by NASA. At the time of a review last month, ICEMAG’s estimated cost was $45.6 million, $16 million above its original cost trigger.

“The level of cost growth on ICEMAG is not acceptable, and NASA considers the investigation to possess significant potential for additional cost growth,” Zurbuchen wrote in a memo announcing the decision to remove the instrument. “As a result, I decided to terminate the ICEMAG investigation.”

NASA instead plans to add a simpler magnetometer as a “facility” instrument to the mission. The scientists involved with ICEMAG will be invited to remain on the mission’s overall science team.

| “The intent here is that NASA is taking the National Academies’ direction seriously,” Glaze said. “In the future, when we build large missions, large flagship missions, we want to take those seriously.” |

But scientists at the conference raised questions about the decision during the town hall meeting. Even before the meeting, an advisory committee called the Outer Planets Assessment Group outlined its concerns in a “special findings” document. “To those not involved in the process, this news came as a complete surprise,” the group said of the decision to remove ICEMAG, saying NASA needed to be transparent because the instrument team “received a seemingly punitive decision that is disproportionate to the challenges faced by the team.”

Glaze said that cost growth alone was not the only reason for removing ICEMAG. “The emphasis is not so much on the overall cost growth but on the other risks that were inherent in the design and the approach that was going forward,” she said. “Most of the concern had to do with the future risks and the fact that instrument was not stabilizing.”

Europa Clipper was being treated differently than Mars 2020, whose instruments aren’t being considered for removal, because Europa Clipper is in a much earlier phase of development. “Part of what we’re trying to do with the process that’s being implemented on Clipper is to try and not end up in the same position” as Mars 2020, she said.

It’s also a sign, she said later, that NASA is taking seriously guidance from National Academies committees not to let cost overruns on flagship missions impact the overall balance of large and small missions recommended for the overall planetary program. “The intent here is that NASA is taking the National Academies’ direction seriously,” she said. “In the future, when we build large missions, large flagship missions, we want to take those seriously.”

Congress, no doubt, will be taking those issues seriously as well as it considers the agency’s budget request in the coming months.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments subcommitted to deal with a surge in spam.