The role of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in supporting space property rightsby Wes Faires

|

| What is needed is a base-level favorable affirmation of private property rights in outer space, one that serves as a foundation for their evolution beyond national borders and which is accepted across the board. |

Opposition has fluctuated from the position that the prohibition of national appropriation in Article II served to exclude development of property rights for private citizens: without a national entity with the ability to “confer” or pass down property rights to “sub-national” citizens, forward progress is rendered impossible. There were later attempts to classify private citizens as “nationals” in order to apply to them the prohibition of ‘national appropriation’.

The 1979 Moon Agreement places an explicit ban on property for a host of entities, including “natural persons,” until such time as an international regime can be formulated.

Two nations, the United States and Luxembourg, have enacted legislation favorable to property and mineral rights regarding space resources. This was met with opposition from some in the international community, who called into question whether such unilateral acts were in and of themselves a violation of the non-appropriation principle of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty.

Perhaps in the future, the concept of “property rights” will have evolved beyond the terrestrial concepts of ownership, sovereignty, and territorial acquisition, under a new treaty framework structured by private entities, developed outside the auspices of any nation-state or supranational regime.

Until such time, what is needed is a base-level favorable affirmation of private property rights in outer space, one that serves as a foundation for their evolution beyond national borders and which is accepted across the board. To this end, the solution to 50 years of ambiguity regarding private property rights under the under the current UN Outer Space Treaty framework is found within the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), Article 17:

(1) Everyone has the right to own property alone as well as in association with others.

(2) No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his property.

-UN General Assembly. "Universal Declaration of Human Rights." United Nations, 217 (III) A,1948, Paris, Art. 17

The commercial space sector would welcome language favorable to private property rights in space, with specific emphasis on the re-affirmation of Article 17 as it pertains to property rights for private entities. Beyond Article 17, utilization of the UDHR as a default mechanism in situations where legislation is not yet developed can yield an immediate benefit for humanity.

| The task at hand is to compel the United Nations Committee on Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (UNCOPUOS) to commit to upholding the Universal Declaration of Human Rights |

On the national level, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights can be seamlessly integrated into national space policy. Adoption of the UDHR into space policy by state parties to the Outer Space Treaty is essentially a reaffirmation of one of the fundamental principles of the United Nations, and can take place without litigation or implementation of new national legislation, and with no accusation of violation of “national appropriation.”

In the international arena, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights can be seamlessly into to conducting legislative proceedings pertaining to outer space, given that:

- The overarching thematic priority for UNISPACE + 50 and beyond is “Sustainable Development in Space.”

- A critical aspect of this calls for ensuring the principles of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development are upheld.

- The 2030 Agenda is grounded in, and re-affirms, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (A/RES/70/1 para. 10, para. 19).

The task at hand is to compel the United Nations Committee on Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (UNCOPUOS) to commit to upholding the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Solidarity on such a core foundational UN principle as the UDHR solidifies reflection of Agenda 2030. I propose that UN Secretariat take this opportunity to move forward with Sustainable Development, and lead the way in incorporation the Universal Declaration of Human Rights into international space policy.

It is time to recognize property rights as the universally declared human right that it is: “Everyone has the right to own property alone as well as in association with others.” The definition of property and scope of the UDHR was not limited to any one definition or territory. The UDHR was intended from the outset to be universal:

“It is not a treaty; it is not an international agreement […] It is a Declaration of basic principles of human rights and freedoms, to be stamped with the approval of the General Assembly by formal vote of its members, and to serve as a common standard of achievement for all peoples of all nations.”

-Eleanor Roosevelt, “On the Adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights” December 9, 1948

Here in its 70th year of adoption, acceptance of the UDHR into space policy by the international community would be both timely and logical. It reaffirms adherence to a fundamental United Nations cornerstone, and provides an opportunity to strengthen the commitment to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

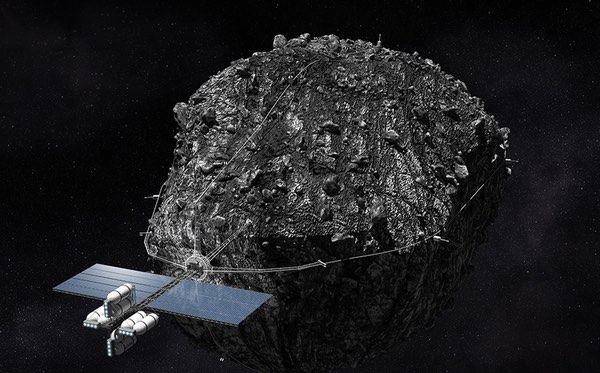

At a time when feasibility of extraction of minerals from celestial bodies is fast approaching, it is our responsibility to ensure that the transition occurs free of any terrestrial shackles. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights offers an acceptable foundational framework from which property rights can evolve off-planet, that can be embraced by the private sector, adopted across national levels, and upheld in the international arena.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments subcommitted to deal with a surge in spam.