The long night: Project Van Winkle comes to an endby Dwayne A. Day

|

| Surprisingly, in 1967, somebody in the National Reconnaissance Office had an idea to save something for posterity, meaning the day when it might be declassified, whenever that was. |

When the men (and few women) were building the first-generation reconnaissance satellites in the 1960s, they also operated under severe restrictions. They knew that they couldn’t tell their friends and families what they did, and they also believed that they would never see the systems they worked on declassified. Many of them probably assumed that when a project was finished, all the records and leftover equipment would be destroyed. And in fact, some of that was true. There were over a hundred CORONA reconnaissance satellites that operated during the 1960s returning their film to Earth in (literally) gold-plated satellite recovery vehicles, and today only a handful of those recovery vehicles remain. What happened to the rest of them? Air Force security personnel punched holes in them with axes and threw them out of a C-47 airplane off the California coast because the vehicles were classified. Even as junk, they were still too sensitive to send to a junkyard.

Surprisingly, in 1967, somebody in the National Reconnaissance Office had an idea to save something for posterity, meaning the day when it might be declassified, whenever that was. In August 1967, Director of the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) Alexander Flax asked the Commander of Strategic Air Command—which had responsibility for Vandenberg Air Force Base—to implement Project Van Winkle, the long-term storage of two KH-7 GAMBIT-1 high-resolution reconnaissance satellites, which the NRO no longer planned to fly now that the more powerful KH-8 GAMBIT-3 was in operation. Flax also asked that the SAC commander “ensure that each succeeding commander of Strategic Air Command and commander of Vandenberg Air Force Base be made aware of Project Van Winkle and all restrictions related thereto.”

“Two sets of certain classified satellite hardware from Program 206 are being readied for long term storage at Vandenberg AFB,” states a declassified memo from that time. “It is intended that this hardware be released to the Air Force Museum and the Smithsonian Institute for display purposes at some future date to be determined by the Secretary of the Air Force.”

Nearly a year later, in August 1968, the satellites were in safe storage at Building 1538 at Vandenberg, part of a complex of buildings originally created for testing Atlas ICBMs. They were in storage containers with specific orders that the storage site could not be changed without prior written approval from the Secretary of the Air Force. The external view of the storage containers was unclassified, but plaques were placed on each container “indicating the contents are non-explosive and non-hazardous and that Secretary of the Air Force approval is required to move or open the containers.” They had to be stored under “positive security control,” which presumably meant that the location had to have armed security on the premises, not simply a locked door. Nobody wanted some curious or drunk airman at Vandenberg to go exploring one afternoon and stumble across the satellites.

Also placed inside the storage containers were the “GAMBIT Program Summary Report” and six rolls microfilm copy of summary report appendices. The documents were void of any security classification markings.

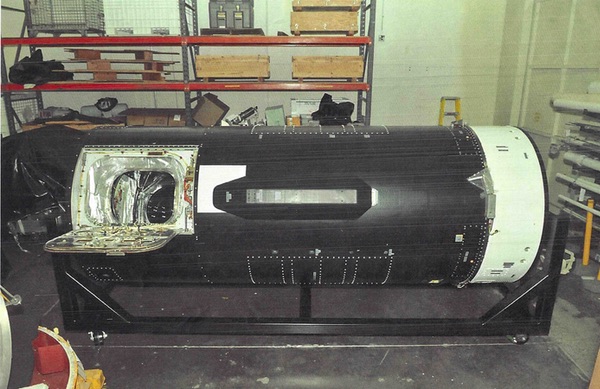

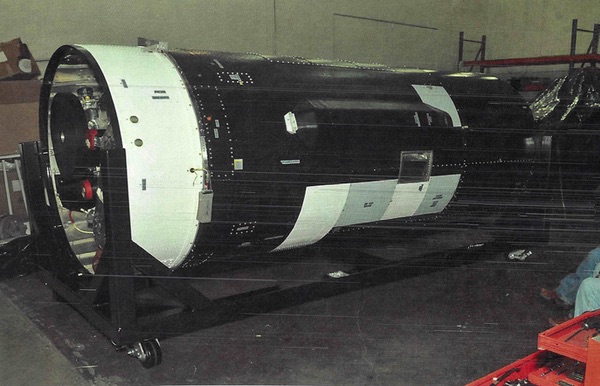

Previously unpublished photo of a KH-7 GAMBIT-1 satellite after removal from storage after over 40 years. Two such satellites were placed in storage in the late 1960s with the intent of eventually displaying them in the Smithsonian Institution and the National Museum of the United States Air Force, where they reside today. Source: JP II |

Locked in their containers, the two satellites sat as the years rolled by. Eventually they were likely joined by other equipment as well, also with the same instructions. The outer shell (but not the optics) of a KH-8 GAMBIT-3 satellite joined them. By the 1980s a new, much larger crate moved in, this one containing the ground engineering camera and associated systems for the schoolbus-size KH-9 HEXAGON. Another piece of hardware that was also added was a cruder engineering mockup of the HEXAGON (that has still not become public). Other crates showed up as well with hardware such as the film-takeup equipment for GAMBIT and HEXAGON cameras, and then probably a bunch of crates with cameras for the retired SR-71 Blackbird spyplane.

| Today, inside some secure facility, probably at Vandenberg Air Force Base, there are undoubtedly other storage containers. Maybe someday they, too, will be opened and their contents shipped to a museum. |

Around 2010, the NRO began plans to declassify both the GAMBIT and HEXAGON programs and the boxes with the GAMBIT-1 satellites were opened up, like Dracula’s coffin, for the first time in decades. One of the GAMBIT-1s was taken to the East Coast and for one day in September 2011—eight years ago last week—was placed on display at the Smithsonian’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Museum near Dulles International Airport, and just a stone’s throw down the road from NRO Headquarters (see “Big Black throws a party”, The Space Review, September 19, 2011). Soon one of the GAMBIT-1’s was placed on permanent display in the National Museum of the United States Air Force outside of Dayton, Ohio, along with the HEXAGON. And a couple of years later the other GAMBIT-1 was placed on display in downtown Washington, DC at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum. Some GAMBIT hardware also went on display at a science museum in London, and some HEXAGON hardware was recently unveiled at the International Spy Museum in Washington, DC. It only took four and a half decades from the signing of that order for Project Van Winkle to finally come to its conclusion.

Today, inside some secure facility, probably at Vandenberg Air Force Base (but not Building 1538, which has been razed), there are undoubtedly other storage containers. Some of them are possibly very big, maybe as large as the one that contained the HEXAGON. Inside may be other retired satellites, maybe some leftover versions of long-dead signals intelligence programs, or even a KH-11 KENNEN engineering model. Maybe someday they, too, will be opened and their contents shipped to a museum. And maybe, tucked behind one of them is a wooden crate, silently humming, and inside is the Ark of the Covenant.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments subcommitted to deal with a surge in spam.