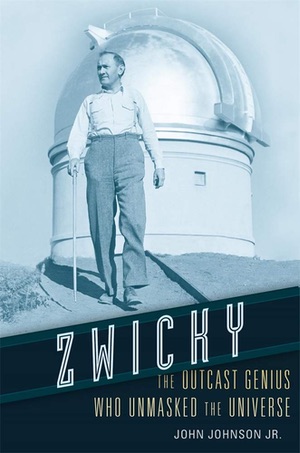

Review: Zwicky: The Outcast Genius Who Unmasked the Universeby Jeff Foust

|

| He had his share of original ideas in astrophysics, some which were brilliant and others that missed the mark. |

As former Los Angeles Times science reporter John Johnson Jr. recounts in his excellent biography of Zwicky, the Swiss astronomer, who spent his career at Caltech, could be difficult to work with. But he was also a brilliant man whose contributions extended from supernovae and dark matter to rocketry. “Like the great forces he chronicled, Fritz Zwicky distorted the orbits of everyone who came in contact with him, attracting many, driving away just as many,” Johnson writes.

Zwicky did not have a lifelong interest in astronomy. He grew up in a family that lived for many years in Bulgaria, pursuing business interests, and was educated at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, where he joined the faculty in physics after graduation. Visiting Americans in the mid-1920s, though, offered him a fellowship at Caltech, which was emerging as a hotbed of physics and astronomy under the leadership of Robert Millikan. Zwicky later became a professor there, where he informed Millikan that he had a “new idea” every two years: “You name the subject,I’ll come up with the new idea.”

“All right young man,” Millikan replied. “Astrophysics.”

He had his share of original ideas in astrophysics, some which were brilliant and others that missed the mark. He proposed that a supernova explosion was the transition of an ordinary star into a neutron star shortly after the neutron itself was discovered. He argued that the redshift of objects could be explained by “tired light” rather than the expansion of the universe, a view he held to even as evidence mounted in favor of an expanding universe.

In one 1933 paper where he discussed the Coma cluster of galaxies, he concluded that the density of the galaxy had to be far greater than explained by observed matter to keep it from flying apart. “If this would be confirmed we would get the surprising result that dark matter is present in much greater amount than luminous matter.” That is one of the first mentions in the scientific literature of “dark matter,” which astronomers know today to far outnumber ordinary matter, even if they still don’t know exactly what dark matter is.

Zwicky’s work went beyond astrophysics, though. In World War II he served as a consultant and head of research for a company spun out of Caltech to make rocket motors: Aerojet. (See “Review: Escape from Earth”, The Space Review, July 29, 2019, for a review of a biography of one of Aerojet’s founders, Frank Malina.) As World War II came to an end, he went to Germany to review its scientific capabilities and was one of the first to interview Wernher von Braun after he surrendered to the Americans. He also was among the first American scientists to go to Hiroshima after its atomic bombing.

| “Had he been more willing to compromise and see the wisdom of others’ views, he would likely have won acclaim rom his colleagues,” Johnson writes. But, if he “had gone along to get along, he wouldn’t have been Fritz Zwicky.” |

Zwicky had no shortage of iconoclastic ideas: either eccentric or prescient, depending on how they played out and one’s point of view. As World War II started, he sought audiences for what he said was a radical new concept for warfare that could make it possible for a relatively small army to defeat Nazi Germany: it involved the use of autogyros—precursors to modern-day helicopters—for attacking forces. It was not adopted, but something like it came to use in Vietnam and later wars. He later promoted a concept for a high-speed tunneling device called a Terrajet, which was never built but which echoes today with what Elon Musk’s The Boring Company is doing.

While brilliant, Zwicky could be difficult to give up on ideas, and would criticize people he thought didn’t give him credit for his work. That abrsiveness ultimately alienated him from working with the US military, in part because of his steadfast refusal to give up his Swiss citizenship and become a naturalized US citizen; and also with fellow astronomers, who cut him off from accessing telescopes at Palomar and Mount Wilson upon reaching retirement age. Those astronomers, Johnson argues, controlled the narrative about Zwicky in the years after his 1974 death, transforming him “into either a cartoonish bumpkin or an agent of pure malice.”

Johnson concludes that Zwicky’s reputation as a difficult person stemmed from his “lone wolf” approach to science, rather than collaboration. “Had he been more willing to compromise and see the wisdom of others’ views, he would likely have won acclaim rom his colleagues,” Johnson writes, describing some of the potential collborations he could have pursued. “But if he had done all those things, had gone along to get along, he wouldn’t have been Fritz Zwicky.” Fortunately for astronomy, rocketry, and other fields, he remained true to himself, even if that self was difficult to get along with.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments subcommitted to deal with a surge in spam.