A vision for commercializationby Jeff Foust

|

| “Our target, in the 2018 timeframe, is to make the seventh human lunar landing,” Shank said. |

Nonetheless, the are some details about those changes, from mission architectures to launch vehicle development, that have leaked out in recent months. Perhaps the clearest picture of NASA’s latest exploration plans came out of the Space Frontier Foundation’s Return to the Moon conference held last week in Las Vegas, where NASA officials offered a broad outline of the agency’s new approach to carrying out the Vision. Just as important as the technological approach to returning humans to the Moon, though, is NASA’s realization, made clear at the conference, that the agency cannot return to the Moon without an unprecedented degree of commercialization.

Target 2018

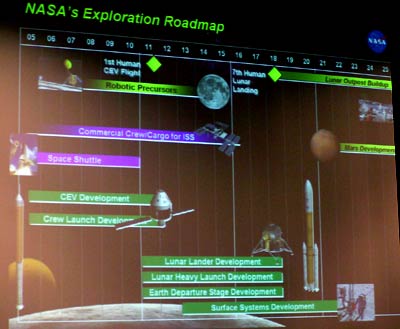

While many details of NASA’s new exploration architecture have yet to be released, Chris Shank, a former Capitol Hill staffer who became special assistant to the administrator shortly after Griffin took over NASA, offered a general roadmap during a presentation at the conference. The near term—through the end of the decade—features the flyout of the space shuttle as it completes the International Space Station by 2010, as well as the development of the Crew Exploration Vehicle (CEV) and a launch vehicle for it, with a first manned CEV mission planned for around 2011.

After 2010, the focus of the exploration plan would shift towards human missions to the Moon, with the development of a heavy-lift launch vehicle, Earth departure stage, lunar lander, and other systems needed for human crews to live and work on the lunar surface. Robotic precursor missions to the Moon, starting with the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter in 2008, would continue through much of the decade. “Our target, in the 2018 timeframe, is to make the seventh human lunar landing,” Shank said, alluding to the six landings that took place under the Apollo program. Future human missions, he said, would follow to gradually build up a permanent outpost.

|

The technical details of those human lunar missions will not be surprising to those who have either followed the debate on the topic in recent months, or who remember Apollo. “One of the lessons that we’ve had from this exploration systems architecture study, at the large level, is, ‘Boy, those guys from Apollo were really smart,’” Shank said. “The physics hasn’t changed, and the orbital mechanics hasn’t changed.” As a result, the general mission architecture has a number of similarities to Apollo, including the use of the lunar orbit rendezvous approach, where the lunar lander ferries crews between the CEV, in lunar orbit, and the surface of the Moon.

Another similarity with Apollo is the development of a heavy-lift launch vehicle, one capable of placing 125 metric tons into low Earth orbit. Shank said that NASA looked at using existing EELV vehicles to support lunar missions, but that nine EELV launches would be needed for a single manned lunar expedition. “When you look at that concept of operations and the risks involved with that, you have to wonder why we are limiting ourselves to that,” he said. “That’s why we’re taking a heavy-lift launch vehicle approach to this.”

In his presentation, Shank didn’t say what kind of heavy-lift vehicle NASA preferred to develop. However, his slides featured illustrations of both CEV and heavy-lift launch vehicles that closely resembled some of the shuttle-derived approaches advocated in recent months. Shank later confirmed that NASA had all but settled on shuttle-derived vehicles—hardly a surprise given Griffin’s long-stated preference on the matter. One issue that remains is getting the Defense Department to agree to a shuttle-derived vehicle: the space transportation policy announced at the beginning of the year requires NASA and the DoD to submit a joint recommendation to NASA. Shank, though, suggested that the DoD was amenable to a shuttle-derived approach.

| “We’ve run the numbers, the budget numbers, and we can’t afford this plan—we simply can’t—if we follow the business-as-usual approach.” |

While many aspects of this exploration architecture share similarities to Apollo, Shank made it clear it was not the purpose of the Vision to duplicate Apollo. “You’re looking at much better thermal protection systems and avionics and ground operations,” he said. As a result, each mission—a minimum of two are planned each year—will be able to carry four astronauts to the lunar surface and quadruple the number of crew-hours on the lunar surface compared to Apollo. Also, unlike Apollo, the long-term goal will be the development of a permanent outpost, with the south pole region of the Moon the most likely location. “This is not your father’s Apollo program.”

The need for commercialization

There’s just one problem with this approach: the money’s not there. Shank made that clear in his presentation as he outlined the overall exploration roadmap. “We’ve run the numbers, the budget numbers, and we can’t afford this plan—we simply can’t—if we follow the business-as-usual approach.” He didn’t go into the specifics of what made this unaffordable, although he later indicated that the problems were in the out-years beyond 2010 when NASA had to fund continued operations of the ISS and the new CEV while developing a heavy-lift launch vehicle and other systems needed for a human return to the Moon.

However, as Shank put it, “If there’s one thing about Mike Griffin that industry and stakeholders are learning about, it’s that he’s not a business-as-usual kind of guy… The NASA budget is only so much per year. It is just a matter of what it is you want to do with that money. So we, NASA, need to be smarter customers.”

That opens the door for alternative approaches, including the purchase of commercial services. “NASA needs commercial ISS crew and cargo operations,” Shank said. “If we assume CEV was the only vehicle, in a business-as-usual conservative costing approach, that if we didn’t take a firm fixed-price approach towards our acquisition practices on how we’re going to provide ISS crew and cargo, we could not afford to move on to the Moon. Therefore, we need to take this ISS crew/cargo procurement very seriously.”

That statement is the strongest yet about the role commercialization will play in the overall Vision, a position that has evolved even during the three months Griffin has been in the administrator’s office. In a speech at a Women in Aerospace event in Washington in early May, Griffin talked positively about commercialization but seemed reticent about using commercial services in the heart of the overall plan:

I cannot put public money at risk, depending on a commercial provider to be in my series path. He might decide not to show up for good and valid business reasons. Okay? I can't put return to the moon and crew exploration vehicle capability, I can't put the ability to send humans into low earth orbit on behalf of the government at risk, based on whether or not a commercial provider decides that he actually wants to do it that day. But I can provide mechanisms where if the commercial provider shows up, the government will stand down and will buy its service and its capability from the industrial provider and let them have the competition among themselves.

Now, though, instead of standing down a government service in favor of a commercial service, NASA is intending to rely primarily on commercial ISS resupply services once the shuttle is retired. “For servicing the International Space Station, the CEV is only intended as a backup capability,” Shank said. “That is a hard requirement from Mike Griffin. There were significant discussions on that. So we need to make the proper investments in order to incentivize the commercial industry to be there.”

Stairway to [entrepreneurial] heaven

ISS resupply is not the only program where NASA is trying to promote commercialization. During a separate presentation later in the day, Brant Sponberg, manager of NASA’s Centennial Challenges prize program, announced a new agency effort called Innovative Programs. The program, which is also managed by Sponberg, includes Centennial Challenges as well as some other “unconventional activities” that he said the agency wants to bring together “and make a coherent plan out of.”

| “NASA needs commercial ISS crew and cargo operations,” Shank said. “…if we didn’t take a firm fixed-price approach towards our acquisition practices on how we’re going to provide ISS crew and cargo, we could not afford to move on to the Moon.” |

Innovative Programs features three non-traditional procurement techniques. One, of course, is the Centennial Challenges prize program, and Sponberg unveiled a new prize competition, to develop an improved astronaut glove, during his presentation. The second features service procurements, like ISS resupply. The third is what is known as “other transaction authority”, using funded versions of Space Act agreements with companies.

Sponberg used a viewchart in his presentation that showed a stairstep-like approach for applying Innovative Programs techniques in a wide range of roles. At the bottom, NASA could purchase commercial suborbital flight services for microgravity research, or sponsor prizes for high-altitude and reusable suborbital vehicles. From there, the chart showed various commercial approaches for low-cost launch, ISS proximity operations and transport, and at the top, small lunar transport missions, where NASA could purchase payload services or sponsor a prize for a small soft lander. “We’re trying to design this so that there’s a range of activities that industry can pick and choose from,” he said.

Sponberg sees the program as a way to incubate new technologies and approaches that, if successful, are then handed over to more conventional offices within the agency. “Under Innovative Programs we try out new things and we take them up to a certain point, but there has to be a turnover point where the NASA customer, the normal NASA operator, takes over, or not. Not everything on this will succeed, and we know that. The idea is that we can take some risks with these programs that some of our mainline programs can’t.”

The open conspiracy

Needless to say, NASA’s embrace of commercialization was well-received by conference attendees, many of whom either work for companies trying to grab a share of NASA exploration business and/or have been extolling the benefits of cooperation with the private sector for years. Still, there was some skepticism about NASA’s ability to pull off these commercial efforts, as well as concerns about the agency’s insistence on developing a shuttle-derived heavy-lift vehicle, most likely as a conventional government procurement.

| “This is not about building an outpost on the Moon,” said Muncy. “This is about all the businesses and enterprises that will spring up around the government activity of going to the Moon, however they get there.” |

In response, Jim Muncy of PoliSpace offered what he called “an open and public conspiracy” to get the private sector behind NASA’s plans. He argued that Griffin realizes that he cannot go to the Moon until after the shuttle program ends, but it may be sufficient to simply kill “the worst part of the system”, the orbiter, and let NASA do what it wants with the rest of the system, using the external tank and SRBs to develop new launch vehicles, even if those approaches seem less than ideal. “I’m really not committed to being right, I’m committed to our getting out there.”

By doing so, he argued, it allows activists to claim the “strategic high ground” in the overall fight to promote the commercial settlement of the Moon. “This is not about building an outpost on the Moon. This is about all the businesses and enterprises that will spring up around the government activity of going to the Moon, however they get there.”