SETI politicsby Gregory Anderson

|

| Getting money and striving for respect, however, seems to have put SETI researchers in a box. |

Perhaps logically, the time of SETI has coincided with the UFO era, and SETI researchers have constantly tried to keep their work distinct from those investigating Roswell and Area 51. Part of that effort is straightforward—the astronomers and physicists involved don’t take UFO stories seriously. Part of it, however, is about respectability. SETI researchers are convinced theirs is the way to find sentient life among the stars, and they want to pursue their work without being called crackpots. Research requires funding, and funding demands a certain level of respectability.

Getting money and striving for respect, however, seems to have put SETI researchers like Seth Shostak and Jill Tarter in a box. To justify continuing SETI work, they must argue that the existence of advanced technological civilizations elsewhere in the Milky Way, given what modern science knows, is perfectly possible. On the other hand, however, largely to build the respectability of their efforts, they also argue that interstellar travel is so difficult, and will always remain so, that no civilization will ever master it. That stance accomplishes two objectives. First, it dismisses the idea that UFOs might be interstellar craft. Second, it enshrines SETI—their passion—as the only way to ever answer the question: Are we alone?

Nothing in human history, however, suggests there is a plateau that civilization, science, and technology can reach but never go beyond. Indeed, though human civilization is still young, the sweep of history could be taken to argue exactly the opposite.

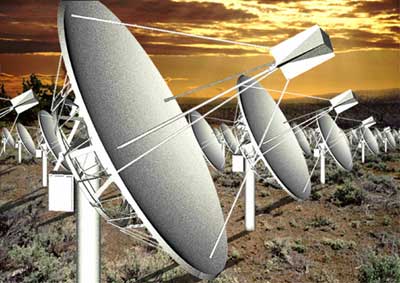

Is interstellar flight impossible? Not theoretically. Humans have already come up with various, seemingly workable, starship designs. Given enough time, human migration to the stars will likely be at least possible. Whether it ever happens is another matter. Dr. Shostak argues that interstellar travel will always be so expensive that societies will always elect to explore deep space through some version of SETI—by communicating through radio transmission or other long-distance means with other civilizations. Scientific research, Shostak seems to assume, will be the only driver of interstellar travel, and will never command the resources in any society to mount such daunting missions.

| Postulating regular communication among related civilizations in several star systems makes a successful SETI effort not only more likely—it makes the effort more defensible. |

Both those assumptions are open to question. First, any civilization in a position to seriously consider interstellar flight will be fabulously wealthy—quite literally, wealthy beyond any human imagination. A society that wealthy may well have an incredibly large budget, and taste, for scientific knowledge; after all material needs are met, new ideas and new physical vistas might be the point of life. Second, if human history is any guide, there will be more than one reason to go to the stars. Scientific research may be one. After all, by the argument of the SETI researchers, those solar systems without transmitting civilizations will be black holes otherwise. Long-term economics and trade may be another driver; establishing English colonies in North America led to extraordinary economic advances over 300-odd years, and a civilization on the edge of interstellar flight could easily consider such time frames in its policy. There may also be political reasons, philosophical reasons, and reasons related to survival. Making one’s species immortal by establishing it in more than one solar system could be the ultimate expression of evolution’s survival drive.

By rejecting the possibility of interstellar migration, SETI researchers might be ruling out the best scenario for the success of their own enterprise. To be successful, humans must be doing SETI at the same time others are transmitting. Postulating unrelated species exchanging information and chattering away makes SETI a crapshoot. Postulating regular communication among related civilizations in several star systems makes a successful SETI effort not only more likely—it makes the effort more defensible. That, of course, would mean embracing interstellar flight as a possibility. Whether SETI researchers are prepared to open themselves to cracks about Little Green Men zipping through spacetime in flying saucers is an open question.