Will a new British space policy arise?by Taylor Dinerman

|

| When it comes to putting the interests of Europe above the interests of one’s own country, Britain should be held up as the least egotistical of all major European nations, at least as far as its space industry goes. |

Hard goals, which the public can understand and appreciate, are things that most governments tend to avoid. John Kennedy said that America would achieve the goal, “before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth.” No ambiguity or wiggle room there. Similarly, the Bush program to return to the Moon no later than 2020 will be judged a success depending on whether or not there is a new set of American footprints on the Moon before January 1, 2021.

Last month the comfortable, bland British space establishment was shaken to the core by an unlikely trio from the Royal Astronomical Society (RAS). Led by the physicist Frank Close, the commission was supposed to investigate the “The Scientific Case for Human Spaceflight.” As Professor Close put it in an interview with the UK journal The Scientist, “Like most scientists, we felt that in the past human space exploration had been driven by politics and that the science had been extremely thin.” Yet the commission came to the opposite conclusion.

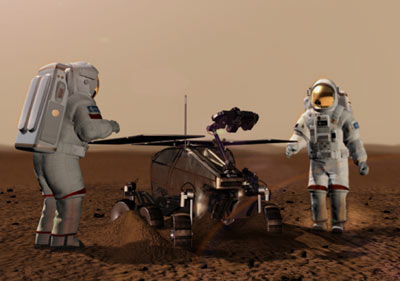

“However, while fully recognizing the technical challenge and the need for substantial investment, we have, nevertheless, been persuaded by the evidence presented to us that the direct involvement of humans in situ is essential if we are to pursue science of profound interest to humankind that can only be undertaken on the Moon and Mars. Autonomous robots alone will be unable to reach those scientific goals in the foreseeable future.” The details of this report will be examined and argued for years to come by those who cling to the old “humans bad, robots good” dogma and their foes.

While many in the establishment scrambled to recover from this bombshell, others have no doubt applauded the commission’s courage in telling the British government and people that, unless they commit to making a much more substantial investment in their space programs, they will not only keep any potential British astronauts stuck on Earth (unless they become American citizens) for a few more decades, but that their nation’s standing as one of the world’s great centers of science and technology will suffer. At a great cost, the UK has kept a prime position in the international marketplace of knowledge and information. That position today may be under some threat.

No matter its size, the modern welfare state and the associated social services such as health and education demand ever greater shares of advanced nations’ incomes. In the US the Bush Administration has increased federal spending on education by 99% according to one recent study. The same study shows that the administration has only increased research spending by about 12%. One suspects that the Blair government’s spending pattern would show a similar imbalance.

| No one really knows what the creative resources of the UK’s space entrepreneurs really are. They have never been given much of a chance. |

The RAS commission’s recommendation that the UK be prepared to spend an additional £150 million (US$260 million) a year on the human side of ESA’s Aurora solar system exploration program is a welcome step in the right direction. But why, one must ask, do they recommend it being spent only on that ESA project? There are plenty of indigenous space programs that could use a modest investment from the British government. The Starchaser team may not have won the Ansari X Prize, and they did put on a spectacular show in New Mexico last month, but they are, as far as one can tell, virtually the only repository of rocket engineering expertise in all of Britain. Surely, the tutelary Gods who rule the destinies of ESA and Eumetsat would not begrudge them a few million pounds to keep them in business.

More to the point, no one really knows what the creative resources of the UK’s space entrepreneurs really are. They have never been given much of a chance. If the BNSC were to emulate NASA’s Centennial Challenge prize idea, they might tease out some outstanding products. “Innovative Space Technologies” are to be found in the strangest places and the UK’s traditional fondness for eccentric geniuses might mean that they may have more to contribute to human spaceflight than we can now imagine.