Just another Apollo? Part oneby Daniel Handlin

|

| Yes, it has been done before, but that does not make the feat of going to the Moon any less spectacular. |

The Washington Post called it “odd”. The Examiner, another DC paper, compared those who want to send men to the moon and Mars to the obsessed Captain Ahab of Moby Dick and said that “There is no reason to believe that now is that time [to send astronauts to the Moon] or that NASA has proven itself completely up to the task.” The Palm Beach Post wrote against the plan, citing “massive hurricane damage, surging budget deficits and a war to fight in Iraq” and criticized the plan as being nothing more than “a more muscular Apollo.” The Los Angeles Times facetiously pointed out that the Moon is not receding from Earth very quickly and that it will “still be around” if we don’t carry the VSE through to fruition. Many other newspapers had similar reactions (see “The reaction to the exploration plan”, The Space Review, October 3, 2005). It is sad that the sense of vision and the drive and yearning to reach for those goals which are just beyond our grasp have been lost since the heady days of the 1960s.

Consider the magnitude of the achievement NASA is contemplating: sending astronauts to the Moon! The reactions of people in 1950 or 1960 to that truly awesome statement were far more understandable and more in line with the enormity of the task than the repetitive and negative reactions seen the in the media today to the same dream of sending men to the Moon. Yes, it has been done before, but that does not make the feat of going to the Moon any less spectacular.

The pieces in the mainstream media that have attacked the ESAS and the VSE in the last several weeks are so formulaic that one might be excused for thinking that every newspaper had made its own edits to a form letter and then published it as an editorial. Virtually everything written against the VSE can be broken down into the same three arguments:

“NASA wants to repeat something it did already for $104 billion.”

“We can’t afford this at a time of hurricane reconstruction, a war in Iraq, and a national deficit.”

“Despite arguments 1 and 2, we like the space program, so we think NASA should use robots instead.”

Interestingly, few of those who write against the space program say that NASA should be shut down entirely—instead, most of them claim a preference for the unmanned space program over the manned program. With regard to the second claim, Administrator Griffin correctly pointed out at the ESAS rollout, “…We’re talking about returning to the moon in 2018. There will be a lot more hurricanes and a lot more other natural disasters to befall the United States and the world in that time… But the space program is a long term investment in our future. We must deal with our short term problems while not sacrificing our long term investments in our future. When we have a hurricane, we don’t cancel the Air Force. We don’t cancel the Navy and we’re not going to cancel NASA.” He went on to describe the thousands of jobs in the Gulf Coast that depend on NASA. The very same arguments were heard against Apollo in the 1960s, only the war was in Vietnam, the hurricanes were called Camille and Betsy instead of Katrina, and the riots and reconstruction were in Chicago and Detroit instead of in New Orleans. The third claim, regarding humans versus robots for space exploration, has been addressed in the past (see “Seeking a rationale for human space exploration”, The Space Review, February 9, 2004).

However, the purpose of this article is not to address the latter two claims in detail. Instead, this article will review the first claim: is the VSE, as fleshed out in the ESAS, a rerun of Apollo? Why should we do something that we’ve done 40 years ago all over again, at a risk to human life and at great cost? Why should we send people to the Moon at all?

“Apollo on steroids”?

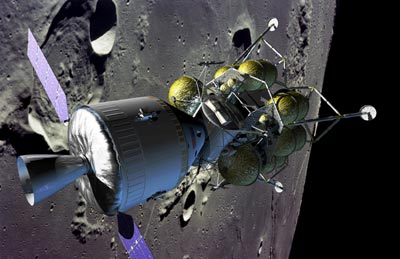

When Michael Griffin was appointed as administrator, he commissioned the ESAS to specify a workable strategy of manned lunar exploration, with a first landing targeted for 2018. He replaced the bloated and absurdly complex working strategy formulated by Sean O’Keefe, which would have involved at least four to six EELV launches for every single lunar mission, and a number of rendezvous operations in Earth orbit and possibly in lunar orbit as well. The new plan does resemble Apollo much more closely, and it’s worth taking a moment to examine its basics. The ESAS includes two new spacecraft, the CEV (Crew Exploration Vehicle, the equivalent of the Apollo CSM) and the LSAM (Lunar Surface Access Module, the equivalent of the Apollo LM), as well as two new launch vehicles.

| Interestingly, few of those who write against the space program say that NASA should be shut down entirely—instead, most of them claim a preference for the unmanned space program over the manned program. |

These two new launch vehicles will both be shuttle-derived. The first will be a medium-lift booster based on a single four-segment SRB with a new liquid hydrogen/liquid oxygen upper stage. This vehicle is sometimes called the Crew Launch Vehicle (CLV) and will be capable of lifting 25 tons to low Earth orbit (LEO). A fifth segment could be added to the SRB for increased payload capability. The second vehicle will be a heavy-lift in-line booster (the Heavy-Lift Vehicle, or HLV) capable of lifting 125 tons into Earth orbit. It will include 5 SSMEs on the first stage, two five-segment SRBs, and an upper stage (called the Earth Departure Stage, or EDS) with two J-2S engines (simplified versions of the Apollo-era J-2 engine that powered the second and third stages of the Saturn V).

In a lunar mission, the HLV will launch first and will place the LSAM into Earth orbit atop a fuelled EDS. Then the SRB-derived booster will launch within 30 days of the launch of the HLV, carrying a crew of four into orbit in the CEV. The CEV will dock with the LSAM/EDS complex in Earth orbit, and the EDS will then fire its engines to place the CEV/LSAM onto a translunar trajectory. This is analogous to the Apollo TLI maneuver, except for the detail that the Apollo CSM did not dock with the LM until after the TLI burn. After the TLI burn, the EDS will be jettisoned and the CEV/LSAM will cruise to the Moon. The LSAM will conduct the Lunar Orbit Insertion (LOI) burn using its LH2/LOX descent engine, and then the crew of four will fly the LSAM to the lunar surface to explore the lunar surface for four to seven days (on initial missions). When the crew is ready to return, they will go into lunar orbit in the LSAM’s ascent stage, and dock with the unoccupied CEV. The crew will transfer to the CEV and move samples to the CEV, and will then jettison the ascent stage of the LSAM. Then the mission will finish just as Apollo did, with the CEV firing its engine to place the crew on a trans-Earth trajectory; just before reentry the service module will be jettisoned and the crew will land in the crew module (though on land rather than in the ocean).

On the surface this sounds pretty similar to Apollo. But is it? The similarity of Apollo to the new plan can be considered both technically and programmatically in the short and long term.