A model for the international development of the Moonby Ryan Zelnio

|

| A major shift in how our governments work together will need to come to pass before each country will agree to work with the United States. |

Intelsat began in 1964 with 11 participating countries and launched the creation of the first global geostationary communication satellite the following year. By 1973, there were 80 signatories, and the organization was providing service to over 600 earth stations in more than 149 countries, territories, and dependencies. While its funding came from all participating countries, it was unique in that it developed none of its own hardware but purchased it from commercial companies. By the turn of the century, the path it blazed in developing GEO communication satellites helped nurture a market in which commercial companies spend more on developing near-Earth space than the US government does. Its mission accomplished, it became a purely commercial entity in 2001.

Europe has also made significant progress in developing a framework in which multiple countries can integrate their various space programs towards a common goal as shown in the governance of the European Space Agency (ESA). Through ESA, each country is able to contribute to a greater pool of money that can be used to undertake projects that would be too costly for the member country’s economy to accomplish on its own. ESA has focused its mission on developing an infrastructure within its own borders to be able to foster commercial companies in Europe, and developing technologies that allow it to compete in the space market. Without this framework, it would arguably never have been able to put together the highly commercially successful Ariane rocket and the commercial spacecraft buses used by EADS Astrium and Alcatel Alenia Space.

Four frameworks

To understand the significance of these two instances of international cooperation, it is important to see what other types of cooperation frameworks exist. There are four types of cooperation that are possible: coordination, augmentation, interdependence, and integration.

A coordination framework is when each country has a separate program that is independent of each other but coordinates on technical and scientific matters. This model of cooperation is inviting in that it is easy for people to agree to, as it allows each country to maintain its total independence and manage its own contributions. The disadvantage of this is that often countries push programs that greatly overlap the efforts pursued by other countries, causing much duplication of efforts. This model, however, has been successful for Earth observation and several coordinating groups exist, including the Committee of Earth Observing Satellites (CEOS) and Global Earth Observation (GEO), with varying levels of success.

Augmentation implies that other countries provide for and enhance the project of the prime country but are not on the critical path. This has been a popular path in the United States as it allows for centralized control over the critical path. Missions like Cassini followed this model, with Huygens being contributed by ESA. The disadvantage to this framework is that the bulk of the costs fall upon the prime country. This is the current model that Griffin seems to be pursuing with the VSE.

Interdependence is cooperation on the critical path of the project as well as on functional systems with each participant still controlling their part of the project. This is the framework that the US and Russia have for the International Space Station. This has proven to be extremely costly as neither participant is able to have any effect on keeping the other from slipping on the critical path and causing significant delays and cost increases to the overall project.

| To formulate international undertaking for the development of a lunar base that is a true integrative approach, a new international space agency should be created that will manage the efforts. |

Integration is full cooperation with shared and joint research and development with a pooling of resources. This framework spreads out the financial costs, and utilizes the industries of multiple nations while still maintaining a single entity that controls the critical path. This is the model in which both ESA and Intelsat have worked under and has been proven to be very successful. The main problem with this framework under current policies is that it also maximizes technology transfers, something that would be hard to do under current US technology transfer regulations.

Understanding the choices that we have for frameworks to bring in international partners to fulfill the ambitious aim of the VSE, I propose that a two-phased cooperative agreement be used. The first phase would be coordination between all nations to send robotic spacecraft to the Moon to survey its resources and map its surfaces. The second phase would be an integrative effort to develop a base on the lunar surface. While this approach contains some radical changes to foreign policy, I believe it is needed for a sustainable, long-term presence on the Moon.

Phase 1 - CLES

During the first phase, which can occur immediately, a Committee on Lunar Exploration Satellites (CLES) would be formed, modeled after CEOS. CLES’s primary responsibility would be to coordinate all spacecraft currently in development as well as recommend other robotic missions to the Moon. These missions would include ESA’s SMART-1 satellite already orbiting the Moon, Japan’s Lunar-A and Selene spacecraft, and China’s Chang’e program. It will help foster the kind of cooperation that was cited during Griffin’s speech in which India will be flying two US instruments on a mission of theirs to the Moon.

In addition to these responsibilities, this committee would also have the task of centralizing and distributing all scientific data from these missions to the public. CLES will continue in operation until the implementation of Phase 2 has begun.

Phase 2 - ILDA

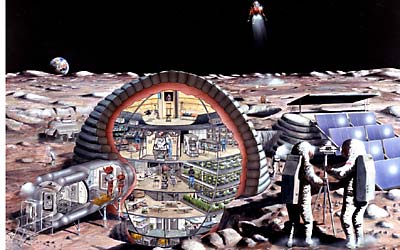

To formulate international undertaking for the development of a lunar base that is a true integrative approach, a new international space agency should be created that will manage the efforts. This agency, the International Lunar Development Agency (ILDA), shall be modeled in part on ESA and in part on Intelsat.

The charter for ILDA is that it shall:

- Develop and maintain a lunar base infrastructure fit for human habitation;

- Develop and administer a transportation system between the Moon and Earth;

- Create the framework needed to develop and use lunar resources;

- Foster commercial development on the Moon and on Earth

Funding rules

ILDA shall have two sources of funding, mandatory funding and voluntary funding. A governing council within ILDA, made up of member states, shall determine the type of projects that fall under the different sources of funding.

Mandatory funding is the money that each member of ILDA contributes in order to claim membership. The amount that must be contributed shall be a percentage based off each country’s Gross Domestic Product. This funding shall cover the core responsibilities of developing a base and transportation for the Moon.

Voluntary funding is optional for projects that fall outside of the core responsibilities of ILDA. These projects include any additions to the lunar base that is not needed to sustain human life, like biological research labs, geology labs, astronomical telescopes, ore processing facilities, and the like.

| ILDA shall encourage commercial development at all times. To encourage this, 90% of all ILDA’s budget shall go to private industry. |

The “just return” principle developed by ESA applies to all projects that fall under voluntary funding. This principle dictates that the work shall be divided amongst industries of each participating country based on the monetary amount each country has contributed. For example, if the United States determines it wants to contribute 42% of the funding towards a lunar solar power station, then they can expect 42% of the work to go to US industries.

Commercial development

ILDA shall encourage commercial development at all times. To encourage this, 90% of all ILDA’s budget shall go to private industry. Furthermore, should a private company wish to fund their own project on the Moon, ILDA shall help accommodate said company. This compensation shall include the use of the transport system and lunar base at fair market prices.

Organizational structure

ILDA shall be composed of four separate divisions, each reporting to the administrator and their office. To further the international aspects of ILDA, each division should be located in a different geographic region.

The Administrative Office shall be located in New York. This location is chosen due to the United Nations (UN). While not a part of the UN itself, it is an organization dedicated to bringing the world together to accomplish a great task and its location shall be symbolic of being associated with the UN. The Office shall include the Administrator of ILDA, the legal division, international relations, and all human resource functions, along with their supporting staff.

The Lunar Base Development division shall be located in Russia in order to draw upon their long-term experience in building living areas in space. This division shall be responsible for the design and development of the lunar base as well as be responsible for maintaining the health of the base itself.

The Lunar Transportation Development division shall be responsible for the design, development, and maintenance of the infrastructure required for travel between the Moon and Earth. It shall be located in the United States to draw upon the experience of the US, as it is the only country that has successfully sent a manned mission to the surface of the Moon and back. In addition to the transportation between the Earth and Moon, this division shall also be responsible for developing methods of transportation on the surface of the Moon.

The Lunar Sciences division shall be located in Japan and shall draw upon the expertise of the Japanese in developing scientific instrumentation as well as the surrounding Asian scientific community. This division shall be responsible for the coordination of all scientific activity on the Moon itself as well as developing new technologies for exploiting the resources on the Moon. In addition to this work, this organization shall subsume the responsibilities of CLES.

The Commercial Development division shall reside in Europe and draw upon the expertise of ESA in working with industry to create new technologies that open new markets. Its role will be in the coordination of commercial interests within plans of the other divisions of ILDA, as well as working with business to pursue commercial opportunities on the surface of the Moon.

Administration and authority of ILDA

The charter for ILDA shall have to be ratified by each individual country and shall have the force of a treaty under international law. All funding shall go through the Administrative Office and the Administrator shall control the doling out of all monetary resources as well as be the ultimate authority in determining contractor selection, within the confines mentioned previously.

| Implementing the type of radical change in how we approach the VSE with an organization like ILDA will not be easy, nor will it happen overnight. Its creation will mark a shift in space policy and how it is implemented. |

The Administrator post shall be an elected position lasting five years. No administrator can serve twice and each subsequent administrator must not come from the same geographic region as its predecessor. The Administrator shall be elected by the votes of each nation that has ratified the ILDA charter. Each nation’s vote shall have the same weight as the percentage of their contribution to the mandatory funding of ILDA. Furthermore, once the participating countries have deemed that the infrastructure is in place enough to be sustainable on its own, ILDA shall cease to exist and be privatized; one estimates that the lifetime of ILDA will be 40–60 years.

In conclusion…

The creation of ILDA provides a framework in which the goals of creating a permanent base on the Moon are open to all countries of the world as well as private enterprise. Its structure is such that it will be able to sustain continued operations on the Moon over the foreseeable future.

Implementing the type of radical change in how we approach the VSE with an organization like ILDA will not be easy, nor will it happen overnight. Its creation will mark a shift in space policy and how it is implemented. It shall force changes in each country’s individual space programs as resources are diverted to fulfill obligations under the ILDA charter. It is also not necessarily the most realistic model to implement. What it is, though, is a way to start to understand the scope of what needs to happen for a true model to be created, if we take seriously Griffin’s remarks about truly bringing in other countries not as just augmentations to our existing vision, but as true partners in the settlement of the Moon.