The effects of export control on the space industryby Ryan Zelnio

|

| The cost of an average GEO communications satellite ranges from $200–500 million, depending on complexity. |

Due to high costs associated with manufacturing facilities, there are only a handful of companies that are capable of building them. There are five companies which dominate the sector: Boeing Satellite Development Center (formerly Boeing Satellite Systems), Lockheed Martin Commercial Space Systems, and Space/Systems Loral in the United States, and Alcatel Alenia Space and EADS Astrium in Europe. There are also a number of smaller companies that fill certain niches in the market: Orbital Space Sciences (US), Israeli Aircraft Industries, Mitsubishi Electronics Company (Japan), Energia (Russia), and the China Academy of Space Technology.

Market trends

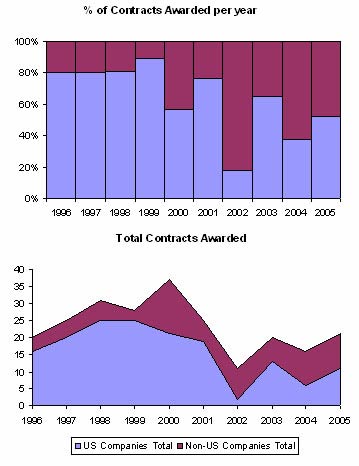

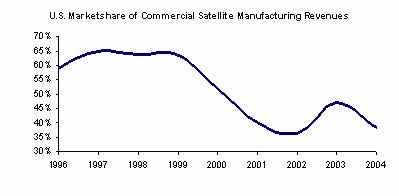

Prior to the change in export controls in 1999, the US dominated the commercial satellite-manufacturing field with an average market share of 83 percent. Since that time, market share has declined to 50 percent (see the figure below). While this cannot be blamed entirely on changes in export regulation, they have played a significant part in the decline . However, since the change in export policy, no Chinese satellite operator has chosen to purchase any satellite that is subject to US export regulations and have instead selected European and Israeli suppliers with over six satellite orders to date since 1999. This comes out to a loss estimated anywhere from $1.5 to $3.0 billion to the US economy. Additionally, China has made a commitment to building up their commercial satellite bus, the DFH-4 by the China Academy of Space Technology. This bus has been successfully marketed to other countries fearing US export policies, including Nigeria and Venezuela.

US vs non-US commercial comsat manufacturing market share |

In addition to the expected movement of Chinese satellite orders from US manufacturers, other operators are increasingly becoming wary of dealing with the US. In 2003, Arabsat decided to award two new satellites to Astrium over its traditional builder, Lockheed Martin, due primarily to their fear of export regulations in holding up delivery . Telesat Canada has also tired of the red tape associated with having to deal with ITAR approval and chose to award the Anik F1R satellite to Astrium. Intelsat awarded the contract of Intelsat-10 (originally a two-satellite contract, although one of the two was later cancelled) in 2000 to Astrium fearing the effects ITAR, though they later awarded Intelsat Americas 9 to the US manufacturer Space Systems/Loral in 2004 as part of a deal in purchasing Loral’s North American satellite fleet.

In addition, US manufacturers are increasingly being weary of bidding on certain foreign contracts. If they anticipate a certain level of ITAR problems, such as was seen on Koreasat 5 with its combined military and civil uses, US companies choose to not even put together competitive bids to win these contracts. In talking with various satellite executives, this is estimated to be around three-to-six non-Chinese contracts since 1999 that have been avoided. Taken in with the losses in the Chinese market described previously, US satellite manufacturers have loss somewhere between $2.5 and $6.0 billion since 1999 due primarily to ITAR regulations.

By far the greatest benefactor to US export policies has been Alcatel Alenia Space, a joint venture formed in 2005 by combining the space businesses of Alcatel and Finmeccanica. In the early 2000s, Alcatel announced that they would create an “ITAR-free” spacecraft. By 2004, Alcatel had been able to double their market share from around 10% in 1998 to over 20% in 2004.

There has also been a major downturn in the economy, particularly affecting the telecommunications industry, over this same period. This downturn has decreased the number of orders going into the industry in general. However, the downturn and subsequent recovery has been worse for the US. The last three-year average (2001–2003) is down 35% for US manufacturers from the previous years (1996–2000).

Satellite manufacturing revenues |

In the near future, this trend will only get worse as revenue lags contract awards by 20–30 months: revenue is added the year a satellite is launched, typically two to three years after the contract award.

Getting the ITAR approval

Another effect that has hindered commercial manufacturers is the length of time it takes to get an ITAR approval. This approval is needed for a variety of reasons including being able to discuss technical performance details with the customer, obtaining insurance for a satellite (most insurers for spacecraft are based out of London), exporting a satellite to a launch base, and being able to talk to ground operators for help with flying the spacecraft.

| US manufacturers are increasingly being weary of bidding on certain foreign contracts if they anticipate a certain level of ITAR problems. |

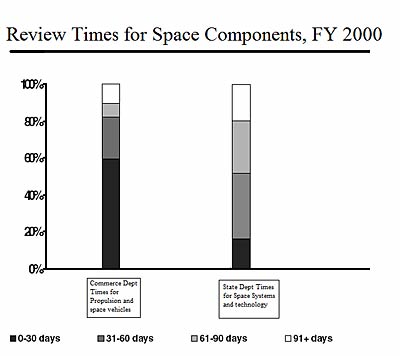

There are many factors that affect the length of time for an approval, including the types of technologies on a satellite as well as the country of export . Due to the large cost of satellites, Congressional approval is also required for export. By law, Congress must either approve or reject any contract within 30 days of its submittal. However, in practice what often happens is that a satellite is not submitted for approval until all questions pertaining to its export license are already answered, a process that can hold it up for months. There has also been some added length as the State Department continues to adjust to the volume associated with satellites and their technologies. As the following figure taken from a report published by the United States General Accounting Office shows, the Commerce Department is generally quicker in approving systems and technologies associated with the space industry.

Review times for Commerce (left) and State Department processing of space components |

This increase in approval cycles has angered many customers from friendly countries and, as previously stated, driven traditional US foreign customers like Telesat to European manufacturers.

Conclusion

Export policy for commercial satellite technologies has been in a state of flux over the past decade and a half. This constant change has had its toll on both the satellite manufacturers and their customers. While the last change was directed at China, it has had a side effect of harming relations between all foreign customers dealing with US satellite manufacturers.

Current export policy has increased the cost associated with doing business for US satellite manufacturers while at the same time decreasing their ability to compete in the global marketplace. Furthermore, it has given an edge to foreign manufacturers, most notably Alcatel Alenia Space. As a result, the US market share in the commercial satellite manufacturing sector has declined and may continue to do so for years to come.

| In space, the US still has the world leadership in experience in satellite manufacturing. In less than one generation, however, that will be gone, in large part due to the effects of export control. |

It is beyond the scope of this essay to examine all the issues detailing the downturn in the satellite manufacturing sector. US export policy is just one factor affecting this. Many satellite operators are partially owned by the governments where they reside and, quite often, satellite purchasing is coupled to the foreign policy aims of that country. In addition, many countries seek to promote indigenous satellite manufacturing capabilities.

Further research is needed into matters of how much of an effect the foreign policy of the countries where other satellite manufacturers reside in has affected their ability to compete. In particular, a closer examination of France’s policy need to be examined to see how that is influencing the growth of Alcatel and EADS Astrium, both of which are headquartered within its borders. France is also a partial owner of Alcatel and that relationship, and its impacts on Alcatel’s growing market share, also need to be researched.

No one country has a monopoly in high technology. Finland, Japan, and South Korea are leaders in the cell phone industry, Japan is the leader in radio technology, and China is the leading TV manufacturer. In space, the US still has the world leadership in experience in satellite manufacturing. In less than one generation, however, that will be gone, in large part due to the effects of export control.