Apocrypha now redux: more space stories that just aren’t trueby Dwayne A. Day

|

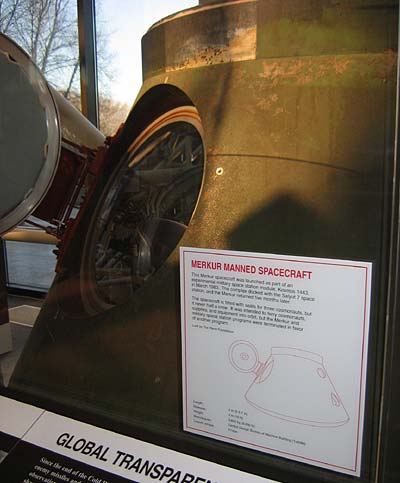

| The problem with the label is that the spacecraft was never designated “Merkur.” In fact, there is no Russian word “Merkur.” |

So how did this artifact come to be mislabeled in the premier aviation and space museum in the world? According to the respected Russian spaceflight magazine Novosti Kosmonavtiki (“Cosmonautics News”): “The American businessman Art Dula recounts, that, when in the 2nd half of the 1980s he visited NPOmash, he was shown a few strange conical capsules in a shop standing next to Almaz [space] stations. The guide, pointing at the devices, said, ‘See, like your Mercury!,’ having in mind the first American piloted spacecraft. The interpreter didn’t catch the phrase and provided without understanding ‘Merkur…’ The word, which doesn’t exist in Russian, stuck firmly to the descent apparatus.”

“I’m probably partly responsible for that misunderstanding,” admitted Russian space expert Jim Oberg in a recent e-mail. Oberg is a friend of Dula’s and he heard how the guide had referred to the spacecraft. “It was just as likely that the host was referring to the similarity in external shape between the two human spacecraft, rather than disclosing a very uncharacteristic use of a classical mythology name,” Oberg explained. “I know that I told the story to others, and I presume that Dula did as well. Before we knew it, ‘Mercury’ became known as the spacecraft’s ‘secret Russian name,’ despite the obvious issue that no other Russian human spacecraft had ever been known, then or since, to have a ‘secret name’ from mythology.”

When the spacecraft was bought at auction by The Perot Foundation along with a number of other space artifacts, the name was attached to it and that’s what the Smithsonian labeled it, despite the lack of corroborating Russian sources. Igor Lissov, the editor of Novosti Kosmonavtiki, has said that Russian space experts consider the mistake to be rather humorous.

The spacecraft in reality is known as the TKS “Vozvrashaemiy Apparat,” or “return craft,” often abbreviated as “VA.” The TKS, which in Russian stands for “transport supply ship,” consisted of two sections: the VA and the “functional cargo block” or FGB. The TKS was a transport ship for resupplying the Almaz military space station. It was known to US intelligence agencies as the Cosmos 929 series spacecraft, and first started flying in July 1977.

According to a declassified 1984 US Air Force intelligence assessment [PDF, 1.3 MB], the spacecraft gave “the Soviets a suitable platform to do research and development on a variety of projects. These projects could include space-based weapons, imaging synthetic aperture radar, ASW research, or other military activities that would require a more secure platform than Salyut.”

In reality, although the TKS worked well in service, it never flew with cosmonauts aboard the VA, nor did it perform any of the missions that the Air Force speculated it could possibly conduct. As a human transport ship it was more expensive than the proven Soyuz. Its primary mission of resupplying the Almaz space station soon disappeared, as military space stations proved to have very little utility for either the Americans or the Soviet Union. The FGB section, however, formed the basis of several scientific modules that were docked to the Mir space station starting in the later 1980s, as well as the Zarya module that is one of the primary elements of the International Space Station.

| Igor Lissov, the editor of Novosti Kosmonavtiki, has said that Russian space experts consider the mistake to be rather humorous. |

As a manned spacecraft, the TKS proved to be a dead-end, and in this respect it shares some characteristics of another dead-end—and often mislabeled spacecraft—the second Soviet space shuttle. According to Russian space expert Bart Hendrickx, this specific craft has often been given an inaccurate name. The first shuttle was named “Buran,” which means “Snowstorm” in Russian, and after sitting in storage in a giant building near its Baikonur launch site, it was destroyed several years ago when the building’s roof collapsed, unfortunately killing several construction workers.

Hendrickx said that many people in the West have reported that the second spacecraft was named “Ptichka,” which means “birdie” in Russian. However, that was never the name of the shuttle, it was simply a nickname that the Russians used for the shuttles in general. The second shuttle was nearly complete when the Russians canceled that program as well. Thus, neither the VA nor the Buran shuttles ever carried cosmonauts. They faded into obscurity, where it was much easier for Westerners to misremember their names.