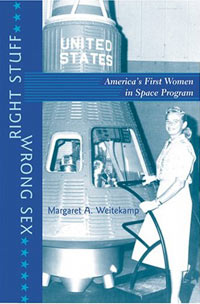

Review: Right Stuff, Wrong Sexby Eve Lichtgarn

|

| Dr. Lovelace was one of the few visionaries who foresaw women in space and he began physical and psychological screening tests of female pilots at his renowned clinic in anticipation of providing qualified candidates. However, the military powers of the day and NASA would not underwrite programs testing women. |

With the end of World War 2, the US government saw no value in space research expenditures. “Fearful of economic downturn as the wartime economy made the transition back to peacetime production,” Weitekamp writes, “government officials hesitated to spend money on research into otherworldly pursuits such as space travel. Although resistance to space research existed well before 1952, under President Dwight D. Eisenhower an especially hostile environment took hold.” Such research was dismissed as “Buck Rogers nonsense.” Weitekamp cites a 1957 speech given by the ranking general of the Ballistic Missile Division “emphasizing the importance of space supremacy for national security. The next day he received a wire from the Pentagon requesting that he not use the word space in his speeches.”

Scientific curiosity was not quelled and during this era, many researchers volunteered themselves as guinea pigs. One such true believer was Dr. William Randolph “Randy” Lovelace II, a key character in Weitekamp’s history. Lovelace personally performed a record-breaking 12,000-meter parachute jump to test his own invention—an oxygen mask—at extreme bailout speeds and altitudes. The blast of freezing atmosphere tore off his protective gear and knocked him unconscious for much of the descent, proving that astronauts did not have a monopoly on the right stuff.

The 1957 Soviet launch of Sputnik opened the spigots of government space spending full bore, but it wasn’t until President Kennedy’s 1961 mandate to send and return a man from the moon prior to 1970 that the spending was directed in a cohesive manner. Dr. Lovelace was one of the few visionaries who foresaw women in space and he began physical and psychological screening tests of female pilots at his renowned clinic in anticipation of providing qualified candidates. However, the military powers of the day and NASA would not underwrite programs testing women. Such activity was seen as an undesirable distraction and certainly not an inevitable adjunct to the Mercury/Gemini/Apollo progression.

Enter famous pilot Jacqueline Cochran—another of Weitekamp’s primary characters. Not only did Ms. Cochran hold many aviation records, she owned a line of cosmetics and perfume and was known to remain in her airplane cockpit applying lipstick after an air race for the benefit of photographers. Ms. Cochran directed much of her personal wealth toward Dr. Lovelace’s program with the caveat that she be recognized as the squadron leader, so to speak. Author Weitekamp does a deft job of portraying Cochran’s ego as big as all outdoors.

It is important to note that in the heat of the space race, the United States scrambled to answer all of the Soviet Union’s space “firsts” except for one. The US played catch-up when it came to the first object in space, the first animal, the first human, the first to orbit, the first rendezvous, the first space walk, and other challenges, but when it came to matching the first woman in space, the US said it wasn’t interested. The domestic confusion over a female space traveler was evident in the weird list of euphemisms appearing in the news: “astro-nette”, “astronautrix”, “feminaut”, and the popular “space girl.” Therefore, the Soviet Union’s Valentina Tereshkova held the record as the only woman in space for some 20 years since her launch in 1963.

| The US played catch-up when it came to the first object in space, the first animal, the first human, the first to orbit, the first rendezvous, the first space walk, and other challenges, but when it came to matching the first woman in space, the US said it wasn’t interested. |

Right Stuff, Wrong Sex is published by Johns Hopkins University Press as part of its “Gender Relations in the American Experience” academic series. While there is no doubt that Weitekamp is an advocate of women’s rights, she is a level-headed advocate. Her judiciousness is most evident in her handling of Jerrie Cobb, one of the more difficult characters in this tale. Cobb was one of the first female volunteers to pass the same medical and psychological tests as those administered to the original NASA Mercury Seven astronauts. She had ample flying hours in prop planes, but because she lacked the requisite jet flight experience, she was never considered as a NASA candidate. Cobb persisted as a vocal thorn in the side of NASA and the agency ultimately co-opted her by making her a consultant to the program, albeit one who was never consulted. Weitekamp handles Cobb’s ultra-Christian zealotry admirably and suggests that Cobb’s own tendency to lose touch with political reality was her undoing.

Weitekamp is the rare historian who sees the big picture as well as the fine detail. Leave it to Weitekamp to put Jerrie Cobb’s 1962 testimony before a congressional subcommittee on science and astronautics in perspective. During the course of giving testimony regarding gender discrimination in the space program, Cobb slipped off her high heel pumps under the witness table. A keen-eyed UPI wire service photographer snapped a shot of Cobb in her stocking feet and many news services ran the photo. Weitekamp writes, “Similar shots, which distracted from the substance of a woman’s contributions by focusing on a momentary slip of etiquette, had been used for years to make military women and other women who challenged traditional men’s realms look ineffective. The shot undercut Cobb’s message about women’s competence.” Given such context, this fine detail identified by Weitekamp isn’t so incidental after all. Right Stuff, Wrong Sex will have you thinking on all sorts of levels.