Lies, damned lies, and cover storiesNew revelations about satellite secrecy during the Cold Warby Asif Siddiqi and Dwayne A. Day

|

| Early in the space age both governments realized that it was possible for the other side, as well as independent observers, to identify satellite missions and programs. As a result, both superpowers sought to adopt and adapt blanket secrecy policies to their space programs. |

Of course, the United States did much the same thing, although on a significantly lesser scale. At one point all US military satellite launches were classified, even those that were entirely scientific and otherwise unclassified. The use of cover stories to conceal the missions of American satellites has apparently diminished greatly since the early days of the space age, but even today the United States uses a generic designation of “USA” followed by a number to label satellites that are classified. The reason is simple: rocket launches are impossible to hide (although some satellites can be concealed by stealth), and international treaties require satellites to be registered, so the government must make some kind of acknowledgement that they exist, even if the government will not discuss their missions.

In the past year, newly declassified information has been released both in the United States and Russia that sheds some light on how and why the superpowers used secrecy to shield their space programs in the early 1960s. This information illustrates that early in the space age both governments realized that it was possible for the other side, as well as independent observers, to identify satellite missions and programs. As a result, both superpowers sought to adopt and adapt blanket secrecy policies to their space programs. In both cases, though, the governments also realized the limitations of blanket secrecy policies towards protecting classified information. The United States initiated a program called Raincoat to shield the development of a highly secret reconnaissance satellite, and the Soviet Union considered adding a new layer of secrecy—and confusion—to their satellite naming system by adopting the Zarya designation. The existence of neither program has been publicly revealed before now.

Melting secrecy

In the United States, the use of cover stories to conceal satellite missions can be traced at least back to the mid-1950s and the operations of the U-2 reconnaissance aircraft, whose very designation—U for “Utility”—was a deception. British writer Chris Pocock, author of three outstanding books on the U-2, has stated that one of the common myths about the aircraft is that it was secret until it was shot down over the Soviet Union on May 1, 1960. In reality, because of the need to operate around the world and the likelihood that the planes would be seen by civilians and military personnel at and near American military airfields, the CIA needed a cover identity for the U-2. In May 1956 the National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics, which was later incorporated into NASA, issued an official statement identifying the U-2 as a weather research aircraft. The Soviets were not fooled, however, because soon the U-2s were flying over their territory and the Soviet military had tracked them back to their airfields.

Although the U-2 provided the most obvious precedent for the newly emerging space program, cover stories had a well-developed pedigree. The Air Force had long claimed that high-altitude reconnaissance balloons were actually weather balloons. One of the great UFO myths, about a flying saucer crash outside Roswell, New Mexico, was perpetuated in large part because the “simple weather balloon” explanation in fact concealed a highly classified high-atmosphere nuclear detection program known as Gopher—a fact that was not publicly revealed until the 1990s. When the CIA started the Corona reconnaissance satellite program in 1958, they used the cover story that the satellites were actually Discoverer research and engineering spacecraft. By 1959 the US Navy had started a signals intelligence satellite called GRAB. The GRAB mission was hidden on a legitimate scientific satellite named SolRad. In fact, many of the people at the Naval Research Laboratory who worked on SolRad were unaware that in the evenings, their satellite was “borrowed” by a group that was installing signals intelligence electronic equipment inside the tiny satellite body.

A significant change occurred in 1960 when a CIA U-2 spyplane flown by Francis Gary Powers was shot down over the Soviet Union. NASA had inherited the NACA’s duty of providing the cover story for the U-2, and the US government claimed that the downed aircraft was a NASA weather research aircraft that had strayed off-course. The CIA hastily repainted a U-2 in NASA colors and displayed it to the press at Edwards Air Force Base. But the cover story quickly crumbled when the Soviet government produced the U-2 wreckage and the pilot. NASA officials were angry that they had been exposed for covering an intelligence program and concerned that this would hurt their ability to make agreements for building satellite tracking stations in foreign countries. Their relations with the CIA did not improve until a new administrator, James Webb, took over the space agency in 1961. However, so far as is currently known, NASA never again provided cover for a military or intelligence program. From that time onward, the intelligence community would only use military cover stories to conceal their satellite and aircraft programs.

| NASA officials were angry that they had been exposed for covering an intelligence program and concerned that this would hurt their ability to make agreements for building satellite tracking stations in foreign countries. Their relations with the CIA did not improve until a new administrator, James Webb, took over the space agency in 1961. |

The Discoverer program presented a different set of problems for the intelligence community. The Corona reconnaissance satellite had originated as an Air Force program that was then turned over to the CIA. The CIA would fund the payloads and provide security for the program, while the Air Force funded the launches and the spacecraft, and provided the cover story that the flights were for research and engineering purposes. The Air Force even announced plans to launch mice and one or two rhesus monkeys aboard the recoverable Discoverer spacecraft in order to conduct biomedical research. The purpose of the cover story was to not antagonize the Soviet government by publicly flying a reconnaissance satellite over their territory. The U-2 was already angering the Soviets and the Eisenhower White House did not want to encourage the Soviets to protest or try to shoot down American satellites. The Soviet government could suspect that Discoverer had intelligence purposes, but it was important that they not be able to confirm or prove it.

When it was first conceived, however, Corona was only going to be a short-term interim program until a larger and more capable Air Force reconnaissance satellite became operational. The initial plan was for only about a dozen flights in all. The cover story was helped by the fact that their Thor rockets could only place a relatively small payload in orbit; intelligence officials hoped that the Soviet government would conclude that the payload was too small to carry a reconnaissance camera. The Americans knew that eventually the Soviets would determine that the Americans would not fly so many “research and engineering” flights. But they hoped to keep the Soviets in the dark for as long as possible, and certainly did not want them to know that reconnaissance cameras were flying starting with the fourth mission.

The Soviets publicly protested the Discoverer launches from the beginning. They apparently suspected as early as 1960 that Discoverer was a reconnaissance program. Their protests did not stop until the Soviet Union finally launched its own reconnaissance satellite in 1962.

After a string of early failures, the first successful Corona satellites returned its film to Earth in August 1960. By this time the program was expanding. The initial plans had been for a dozen launches, but this was increased several times and when the Air Force failed to produce a successor, Corona became a permanent program. As the Air Force launched more and more of the satellites, the cover story eroded, because nobody believed that the United States was conducting dozens of engineering tests, especially since there was little evidence of actual research results from any of these missions in the form of published papers or data. So the intelligence leadership decided to discontinue the Discoverer cover story with the twenty-ninth launch.

Gambit’s Raincoat

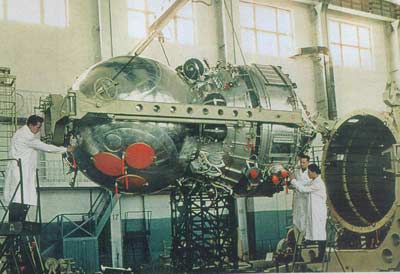

By the time that the U-2 was shot down in May 1960, the intelligence community was already discussing replacing it with a new reconnaissance satellite program. Initially known as “Program I” (as in the Roman number “1”), it was later given the designation KH-7 and the code-name “Gambit.” Gambit was a very powerful camera on a three-axis stabilized spacecraft, and the intelligence community intended for it to replace the U-2 providing high-resolution imagery of denied territory. (In 2002, the intelligence community declassified Gambit photography from 1963 to 1967, but did not release programmatic details about the system.)

A recently declassified government history of secrecy and American military launch operations reveals that when Gambit was first being discussed in the senior levels of the US government, presidential science advisory George Kistiakowsky expressed his concern about the military’s ability to operate a covert program. The Air Force conducted top secret research and operations, but “covert” was a different category entirely. It meant that even the existence of the program was kept secret. The Air Force did not have existing rules, regulations and procedures that allowed this.

Air Force Under Secretary Joseph Charyk strongly argued that Gambit should be developed by the Air Force. He stated that he could prove that the Air Force could develop a covert satellite. In the summer of 1960 Charyk and Colonel John L. Martin, Jr. invented a new security strategy called “Raincoat” that, like a flasher’s overcoat, would be used to shield the naughty bits from unwanted exposure—in this case, covert development of a new reconnaissance satellite.

Charyk and Martin suggested that all military space programs, including those that were purely scientific, would be classified. The idea, according to a government historian, was akin to the saying that “at night all cats are gray.” No publicity would be released on any Air Force space programs, even if they were unclassified. Whereas previously journalists or outsiders (or spies) could look around the military space program for the project that stood out because of its classification, now all projects were shielded with a blanket level of secrecy, making it much harder to find the highly classified programs.

| Charyk and Martin suggested that all military space programs, including those that were purely scientific, would be classified. The idea, according to a government historian, was akin to the saying that “at night all cats are gray.” |

Charyk gained the support of Arthur Sylvester, the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Public Information, and soon afterwards the Department of Defense issued DoD Directive 5200.13, which forbid any publicity release on Air Force space projects. The new reconnaissance program was now covered in a massive blanket of secrecy that also encompassed everything from military communications satellites to scientific research.

The details of the effectiveness of this secrecy program remain unclear due to continued classification, but it is possible to examine how Gambit was covered in the press. Quite simply, it wasn’t. Information on several other reconnaissance satellite projects at the time did leak to the press, usually in the pages of Aviation Week magazine. The stories often contained inaccuracies, but senior leaders in the military and intelligence space programs probably noticed that these programs had leaked, whereas Gambit did not, and concluded that the secrecy program was successful.

Of course, once the rockets started launching Gambit satellites into their highly suggestive polar orbits, it was possible for observers—and the Soviet Union’s military—to speculate that the satellites carried reconnaissance cameras. Other launches to different orbits were also suggestive as well, and amateur satellite sleuths could determine the general category of payload by the launch vehicle, time of launch, and orbit. However, by classifying the entire military space program, the Department of Defense had reduced the leaking of operational and programmatic details of the reconnaissance effort, making it much harder to determine anything about the launches other than their basic mission. Indeed, the true nature of the Gambit spacecraft remained unknown to outside observers for decades. Of course, it would be a mistake to conflate what is reported in the press with what the KGB was able to determine through espionage, telemetry interception, or other means, but clearly the secrecy served as an impediment to understanding the project.

The problem was that issuing a blanket classification of all military space programs had a cost. It was harder for people to work on them because of the requirement for security clearances and the financial costs associated with obtaining them. How much more money was spent on the military space program because of security restrictions imposed to protect only a few programs? We will never know. Furthermore, in an environment where everything is classified, including projects that clearly do not require it, these policies produce a certain amount of contempt toward secrecy among those involved in the programs. Information still leaked, although usually only from the edges and not the highly-classified core projects.

At some point the military loosened the restrictions a bit and allowed public releases of information on unclassified military space programs. The classification of launches lasted much longer, but by the 1980s the Air Force apparently created numerous exemptions for launch operations. For instance, Navstar GPS satellite launches apparently had a blanket exemption from the secrecy directive. However, when a pair of Air Force communications satellites were launched from Space Shuttle Atlantis on mission STS-51J in October 1985, the mission was classified and details were not declassified until the 1990s.