Independent space colonization: questions and implicationsby Taylor Dinerman

|

| If colonization is a dirty word, then so are “conquest”, “exploitation”, “settlement”, and “industrialization”. If fact, anything that goes beyond simple exploration is problematic. |

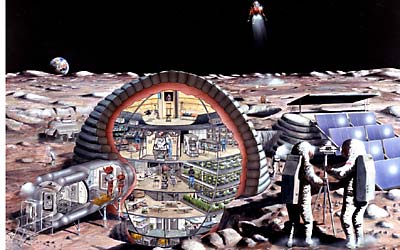

Once one or more bases are established on the Moon, nations will find themselves exerting control over parts of that body which, in practical terms, will amount to sovereignty. Within a moonbase, even one occupied by only a couple of astronauts, the government that sent them there will regulate their lives in more or less the same way a government regulates the lives of the crew of a warship. The ship itself is considered the sovereign territory of the state that owns it while the waters through which it passes may be international or belong to another sovereign state that is obliged to respect the right of innocent passage.

The ship’s crew lacks anything like the ability to function as free citizens and to buy sell and trade in a free marketplace. One question that advocates for space colonization have to consider is: how can the transition from a quasi-military lifestyle to a civilian one be handled? The experience that many communities in the US have had when a nearby military base closed down might be relevant. Another source of experience might be the transitions from martial law to civilian law that have taken place over the years, including the one that happened in Hawaii at the end of the Second World War.

None of these have involved any change in sovereignty. Post World War Two decolonization involved such a change. Yet, if the provision in the Outer Space Treaty (OST) regarding their extended responsibility of launching states for whatever they put into space means anything, it mean that states will have to exercise control over the inhabitants of a colony no matter how long ago their ancestors left Earth.

It is difficult to imagine a third or fourth generation inhabitant of Mars or of another “accessible planetary surface”, to use the old NASA euphemism, accepting the right of a distant Earth government to control any aspect of their lives, let alone the kind of regulations promulgated under martial law. Their reaction to such control might not be a quick and easily mollified revolt, but a more permanent split between the Earthbound and the spacefaring parts of humanity.

In the long term the effort to impose controls on private space colonization by the use of a vague process of international consensus-seeking will create a reaction not only against the OST but against the whole idea that Earth governments should be allowed any say whatsoever in the governance of off-Earth activities. In the near term it is relatively easy for governments to impose their will on space activities, but when vehicles that can provide low-cost access to low Earth orbit are as available to the public as oceangoing private yachts, maintaining control will be much harder.

| In the long term the effort to impose controls on private space colonization by the use of a vague process of international consensus-seeking will create a reaction not only against the OST but against the whole idea that Earth governments should be allowed any say whatsoever in the governance of off-Earth activities. |

Authoritarians, even soft authoritarians, resent the easy mobility that people have acquired with the widespread ownership of private vehicles. A citizen who can pack up his or her possessions and move elsewhere is harder to control than one who is stuck in a village or neighborhood and requires state-controlled public transport to get anywhere. Low-cost space transportation implies a loss of government power.

Worldwide there is a powerful political bias towards ever more powerful government. Long-term technological trends, in materials and biotech as well as in information systems, tend to push the other way. Supporters of the OST will find themselves stuck between these two trends.

The conflict between those in the US who want to revise the treaty to enshrine property rights and a broadly “American” view of human freedom and those with different ideas and priorities makes any revision of the OST problematic. This probably does not mean that the treaty will be junked, like the ABM Treaty was, any time soon, but it does mean that the treaty will have less and less relevance to the future of humankind in the solar system.