Sticky airbags and grapples: kinetic ASATs without the debrisby Taylor Dinerman

|

| Filling low Earth orbit with debris after a successful strike on an enemy satellite is perfectly OK under the terms of the Outer Space Treaty, but no one should expect that it is OK with all the space lawyers out there. |

Dangerous space debris is both man-made and natural, in the latter case in the form of micrometeoroids. Confusing the two is a great way to make the issue into more of a problem than it already is. The environment around Earth is certainly filled with space junk, but if this was as dangerous as has been claimed, spacecraft would be breaking up on an almost weekly basis.

Space junk is a problem and always will be. The international agreements designed to mitigate the dangers have been useful, but cannot halt the creation of more debris any more than recycling laws halt the production of garbage. The trend has been moving in the right direction, at least until our Chinese friends decided to make a statement.

It used to be that in war almost anything that hurt the enemy was OK. Obviously that is no longer true (at least for now) and no Western nation enters into a conflict without a baggage train full of lawyers. This is particularly true for the US. Filling low Earth orbit (LEO) with debris after a successful strike on an enemy satellite is perfectly OK under the terms of the Outer Space Treaty, but no one should expect that it is OK with all the space lawyers out there.

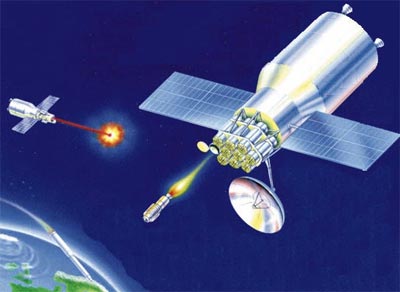

Fortunately, a few years ago a proposal was floated for as class of weapons that would destroy target spacecraft without directly creating any debris. This type of “co-orbital” ASAT would approach its target and envelop it with an airbag covered in a type of sticky substance. It would then fire a thruster so that the conjoined satellites would burn up in the atmosphere. If it worked as designed, no debris would be created.

In practice it would be no easy task to design, test, and operate such a weapon, but it is not beyond the state of the art and would not create any debris. Figuring out what kind of sticky material is right for such a system would, by itself, be a fascinating project. The substance might have applications in other military and perhaps civil space systems.

If the sticky airbag solution proves too difficult, the same goals might be reached using an ASAT equipped with grappling arms that would grasp the target before pushing down towards the atmosphere. The challenges of such a system are evident, not the least of which would be the need for some sort of decision-making software that would choose the best places to seize the enemy satellite during the final moments before contact.

For every military measure there are countermeasures. For this system, one possibility would be to equip a satellite with self-destruct charges that would explode as soon it sensed that it was being enveloped. This negates the purpose of a weapon designed not to produce debris. This might be a difficult mechanism to perfect, especially since it would need to have some way of ensuring that it would only explode if a real danger existed.

| Whatever happens the US should be wary of making too big a deal out of the orbital debris issue. |

This leads, in turn, to the problem of timing. If the charge was designed to explode immediately on contact then debris would be created in the orbit in which the satellite had been operating. However, if the self-destruct system has to hesitate and confirm that indeed the satellite is under attack, the ASAT would have time—a few seconds to a few minutes—to fire its thrusters and change the orbit of the conjoined spacecraft. The closer they approached the atmosphere the likelier it would be for the fragments created by the target’s self destruction to themselves burn up.

Whatever happens the US should be wary of making too big a deal out of the orbital debris issue. All man-made activity in space produces debris. If the US or its allies worry too much about this question instead of simply deciding to live with it, the enemy will find ways of using this concern against the US, like in the case of the “collateral damage” question, where Al-Qaeda, the Taliban, and others learned the lesson that when they kill civilians, they win, and when the US kills civilians, they win.

If America’s space warriors concentrate on their primary mission, which is to defeat the enemy, destroy his space assets, and protect our own, all will be well. If, on the other hand, we end up concentrating on limiting the creation of space debris while avoiding the primary mission, we will hand the enemy a tool they will use to frustrate our goals. War is a dirty, messy business and cannot be waged cleanly, not in Baghdad nor in outer space.