A response to Mike Griffin’s future forecastsby Donald A. Beattie

|

| What happens if LRO is not successful? With such an uncertainty lurking in the background, what is the fallback position if LRO does not return the needed data in 2009 or later? |

The underlying justification that would make these predictions possible, continuing to apportion over 60 percent of NASA’s budgets to human space flight, provides the starting point for questioning his forecasts and reasoning. As a first question, why should NASA continue to spend this high percentage of its limited budget on human space flight? Is it cast in stone that NASA must always spend this percentage? As a result of the FY 2007 continuing resolution, NASA has been forced to reduce, stretch out, or cancel a number of programs while attempting to keep human space flight goals on track. Programs affected include: Earth observation, ISS construction and supply, aeronautics research, developing enabling technologies for all NASA programs (recommended by the NRC as a high priority need) as well as NIAC, and lunar precursor missions, to name just a few. Will out-year budgets eventually make up for this underfunding, or are we witnessing the continuation of tight NASA budgets that will make it difficult or impossible to catch up? Smart money might bet on this last possibility in future years. There is also the question of whether or not other high priority research, such as tracking and diverting near Earth objects, should receive a larger share of NASA budgets than is currently possible.

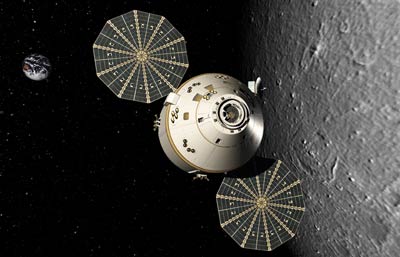

The reduction of lunar precursor missions is especially disturbing. As a result, returning astronauts to the Moon by 2020 is dependent on Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) being completely successful. Without the high-resolution photos of potential sites that only LRO may provide, a landing will not be possible—certainly not if NASA adheres to the caution it followed during Apollo. That is placing a lot of eggs in one basket. Before the first Apollo landing we had five successful Lunar Orbiter missions under our belts that provided all the needed photography for the projected landing sites. Surveyor 3 had landed beforehand at the Apollo 12 site proving that it was a safe and interesting location. What happens if LRO is not successful? With such an uncertainty lurking in the background, what is the fallback position if LRO does not return the needed data in 2009 or later? Should Orion and Ares continue to be funded on a fast track to achieve a lunar landing by 2020 and as a result curtail many other NASA programs?

In addition to these questions, there is the overarching concern among many as to why returning to the Moon is so important and holds such a priority on NASA spending. Developing a fast-paced, comprehensive, Mars exploration program should be among NASA’s highest priorities, but this is not possible within projected budgets. We have already demonstrated our technological leadership in exploring the Red Planet and we should build on this foundation. Whether or not a long-term Mars campaign should include human missions remains to be seen. Information returned from many robotic missions, of various types, must precede any consideration of sending humans to Mars. The sooner we have that data, the sooner we can decide if human missions are possible, or necessary.

In order to assure our ability to continue human space flight after retiring the elegant shuttle, we will be moving forward with a forty-year-old, Apollo-like, capability. Yes, it costs a lot to launch the shuttle and there are risks. However, developing and operating Orion and Ares will not be cheap and there will always be risks in human space flight. Has the arbitrary goal of returning to the Moon by 2020 resulted in pursuing a Cadillac vision on a Chevrolet budget? Continuing to service the International Space Station and providing emergency crew return using modified decades-old Russian technology is a sad state of affairs. Other capabilities may come on line, however, they are not guaranteed. NASA, and the nation, survived a six-year hiatus in manned space flight from Apollo-Soyuz in 1975 until the first shuttle was launched in 1981. The argument that we must keep Orion and Ares moving ahead rapidly because other nations have, or soon will have, human space flight capabilities, is a specious argument playing to the fears of decision makers who hold the purse strings. It is more important to get the next step right rather than try to meet an artificial deadline. Have we started down a path of no return making compromises, as we did for the shuttle, because of budget uncertainties?

| Wouldn’t it be inspiring to finally have an aeronautics and space program that all will agree can be at the cutting edge and affordable for many years to come? |

In nineteen months a new president will be elected. Regardless of which party is in the White House, the new administration and future Congresses will be faced with many difficult problems and decisions. The successful resolution of many, or most, of those problems will depend on agreement on budget allocations. Returning astronauts to the Moon may not hold the same priority with the next administration, or even Congress, as it apparently does today. Almost certainly some changes will occur. Balancing NASA’s research portfolio may become a necessity in the real world of 2009 in order to address some of those problems.

Congress and the next administration must jointly decide what programs will be in the best long-term interest of the nation. Senator Mikulski has asked that a summit be held with the current administration to determine what NASA’s priorities should be. Based on the disarray that currently exists in NASA’s budget, it is certainly a reasonable request. However, even if some kind of agreement is reached, it may only provide a near-term solution to the funding woes and not be in the best interests of NASA’s future. A more important summit should be held in 2009, and language in NASA’s 2005 authorization reevaluated. An administration proposes programs, while the Congress disposes. Wouldn’t it be inspiring to finally have an aeronautics and space program that all will agree can be at the cutting edge and affordable for many years to come?