The Vision hits a bumpy roadby Eric R. Hedman

|

| Like it or not, the current architecture for the Constellation program with some possible variations is that only one that has a chance of succeeding. |

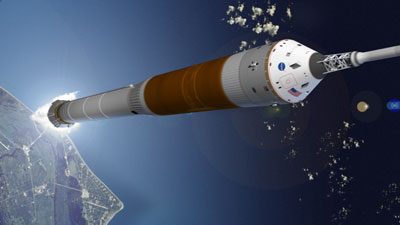

A variety of alternatives to NASA’s vision have emerged that use more of the existing Shuttle infrastructure or the EELVs from United Launch Alliance (see “Another voice in the wilderness”, The Space Review, February 19, 2007). Both have been touted as cheaper and faster alternatives to the current plans. Even if they are, it doesn’t matter. They have little or no chance of being seriously considered. In a world where funding is so tight for NASA, any consideration of these plans would be interpreted as a loss of credibility in the Vision as a whole. It would probably threaten the whole idea of replacing the Shuttle and moving beyond Earth orbit. As much as I would have like to see two plans advanced, and a downselect to one as was done with the Orion capsule, the plan NASA has is for now the only one that has a chance of long-term political viability. The president picked Michael Griffin to lead NASA and Congress is not going to push for a switch to an alternative. Like it or not, the current architecture for the Constellation program with some possible variations is that only one that has a chance of succeeding.

The most unusual problem that was probably on no one’s radar previously was the fact that the Senate couldn’t agree on fiscal 2007 budgets for NASA and many other agencies. It came at a most critical time for NASA. It is probably the biggest threat to the Vision because of the potential for delay. If the next president doesn’t support going back to the Moon, the less progress made on the Vision by January 2009, the easier it will be to kill or radically scale it back.

The space science community is upset that their programs are being raided to keep the Orion and Ares 1 programs on track. I only partially agree with that reasoning. Another reason is that NASA’s share of the federal budget has been steadily falling. Space science isn’t only competing with the manned program. It’s competing with other non-space uses for federal money. When people try to justify spending on NASA I frequently note that NASA’s budget is only six tenths of one percent of the federal budget. It’s said with pride that seems to try to make it the permanent level for the agency. The problem is that, as a percentage of the federal budget, NASA’s share has steadily fallen. It peaked at an unsustainable 4.4 percent of the federal budget in 1966. It held steady at one percent of the federal budget from 1989 to 1993. It has been in a slow steady decline ever since.

Instead of competing against each other for a share of a shrinking pie, the space science community and the proponents of human spaceflight need to work together to expand the share of the federal budget spent on NASA. The goal should be to get back to the one percent of the federal budget that NASA had under the first Bush administration by the middle of the next decade. With that level of funding, NASA could accelerate the development of the Constellation program to narrow the gap between its first flight and the end of the Shuttle program. NASA could once again start flagship planetary missions that could really advance space science. A Mars sample return mission could be accomplished, as well as a mission to the intriguing icy moons of Jupiter. Humans in the loop of space science on the Moon and later on Mars could really advance our understanding of the universe. Enough could be spent on the COTS program to develop a private commercial launch industry to send people and cargo to and from Earth orbit.

Will it happen? Not if the people with an interest in space compete against each other instead of fight for a bigger share of the federal pie. Going out and backing space exploration by saying it is only one percent of our federal budget sounds to the average taxpayer not much different than six tenths of one percent. The difference in what it could be accomplished with the difference is truly like night and day.

I’ve been told by politicians that we can’t afford to spend more on space. When a supplemental spending bill for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have significantly more in earmarks for pork spending projects than is spent in total on NASA each year, I don’t buy the argument anymore. As a nation we turn a blind eye to pet vote-buying projects buried in spending bills. We do not have a serious debate on what we choose to afford. If we choose to afford to spend one percent of the national budget on space, we will return to the projects that inspire our youth and dazzle the rest of the world.

| If we choose to afford to spend one percent of the national budget on space, we will return to the projects that inspire our youth and dazzle the rest of the world. |

So what happens if the next president kills the Vision? Will the US retreat from its space leadership position? Will we have to count on Russia to access the ISS until its retirement? It’s possible that spending on COTS will speed up, but I doubt it. I believe that if the next president doesn’t back the plans to return to the Moon, that any chance to move beyond Earth orbit will be pushed off for another generation. With a reduction or elimination of spending on human space programs, unmanned space science could get a boost, but I doubt it. Why would there be much public pressure for a sample return mission to Mars if there isn’t the possibility within another few decades of humans following?

To get past the current bumpy road, NASA plain and simply needs more money and they need to spend it wisely. NASA needs to tune their vision so that it gets support from all parts of the space community. Past predictions of where the space program would be heading have for the most part been off the mark on either the too optimistic side or the too pessimistic side. Michael Griffin recently laid out where he thinks the space program could go in the next fifty years. I don’t want to guess that far out. If the space community could unite on a vision that benefits all parts there is a chance that all segments could benefit significantly.

If NASA could get back to the funding at one percent of the federal budget, I think that by 2020 low Earth orbit could be the domain of the commercial space community. With the help of NASA, the ISS and future stations manufactured by Bigelow could have a choice of commercial launch providers. Both manufacturing and orbital tourism could finally be solid growing businesses creating new profitable segments of our economy. NASA would be flying regularly to its base on the Moon and planning for commercial resupply that could lead to private bases and industry on the lunar surface. NASA would have samples on the way back from Mars, helping to finalize a design for the first human outpost. At regular intervals, large flagship-class missions would depart to interesting destinations in our solar system. Geologists will be exploring the Moon in depth, giving us a better idea of how our solar system evolved. More research will be done on revolutionary approaches to space travel. The technology spinoffs that help the rest of the economy would continue to flow.

I don’t really know if it’s possible to push NASA spending back to the levels of the first Bush administration. I would like to stay optimistic and think that it’s possible. It all comes back to money. A push for more money for the agency as a whole is needed. I see great value in all aspects of what NASA does. It is time to push for real growth in NASA’s budget. I see a role for the traditional companies like Boeing and Lockheed Martin, but I also see a role for the newcomers like SpaceX, Bigelow, Virgin Galactic, and others. A strong commitment to NASA would be a signal to venture capital firms that now is the time to ratchet up their investments in what could be new opportunities with explosive potential. The future with a smoother road can be purchased with One Percent.